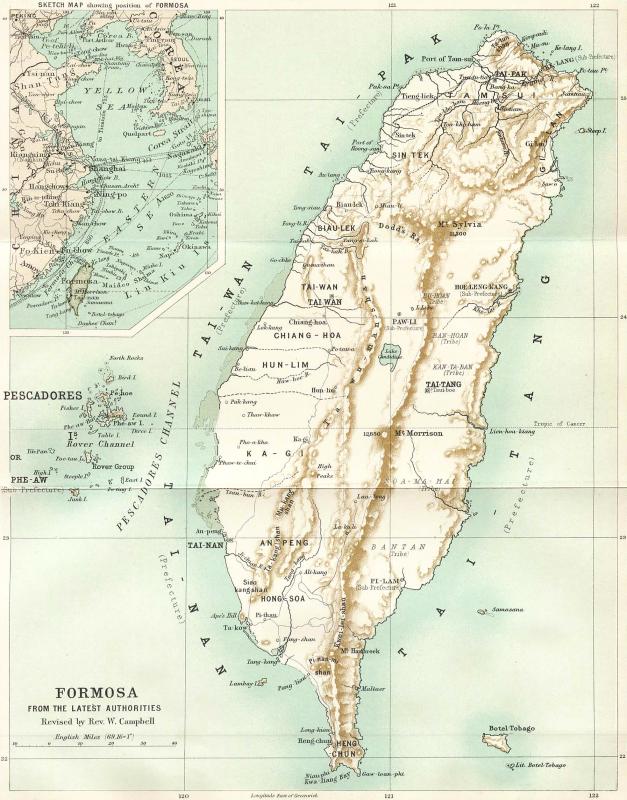

The second expedition of Commodore Matthew Perry of the US to Japan in 1854 sent ships to Formosa on the way back to the US to assess Keelung’s potential as a coaling station. Far-sighted, Perry recommended that the US establish a presence on Formosa, as Taiwan was then known. His suggestion went unheeded, but others were watching, few more closely than Prussia.

The Prussians had wanted to follow up the Americans with an expedition of their own. In 1858, when William I became regent, the idea of entering the colonial race in the Far East began to take shape in the Prussian policy imagination. Prussia Far Eastern policy would exhibit an off-again, on-again yearning for the island, until the Japanese put a lid on it in 1895 when they annexed it.

PRUSSIAN FAR EAST EXPEDITION

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

In August of that year the Prussians made the decision to send an expedition to the Far East. It was headed by Count Friedrich Albrecht zu Eulenburg, who was not a career diplomat but a commercial expert, signaling that the expedition was primarily commercial in nature. Eulenburg, who then had no experience of the Far East, traveled to Paris in the early spring of 1860 to meet with British and French diplomats.

According to historian Bernd Martin (“The Prussian Expedition to the Far East, 1860-1862”), the representatives of the two powers encouraged the Germans. The French diplomat Jean-Baptiste-Louis Gros, who had commanded the French troops in the Anglo-French Expedition in China from 1856-60 and was a famous photographer and politician, suggested to Eulenburg that the Prussians occupy Formosa.

Gros argued that a Prussian colony in Formosa would help blunt southward pushes by the Chinese and British, and support the French in Vietnam. In his book France and Germany in the South China Sea, c. 1840–1930, Bert Becker describes how Gros contended treaties alone were insufficient for supporting commercial enterprises in the Far East. Prussia would need a colony.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia

Eulenburg’s expedition was a success in Prussian eyes. After beating out treaties with the Chinese and Japanese, Prussian policy turned to Formosa, which Eulenburg had initially considered the best prospect for a German colony.

With the Prussian expedition was explorer, diplomat, geologist and ethnographer Ferdinand Freiherr von Richthofen, a man who would be involved with Prussian ventures in the Far East for the next quarter-century. Today he is best known for coining the term “Silk Road.”

Richthofen was sent to Formosa to evaluate its potential for a commercial and naval port and become the German Hong Kong, an idea that colored German perceptions of their colonial policy in the Far East for decades, a reminder of how British colonialism remained the model for would-be colonialists.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia

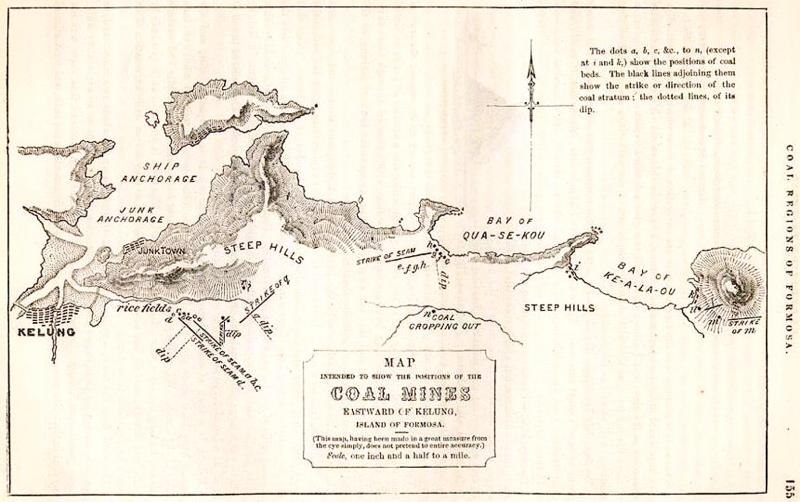

Richthofen also made a geological survey. He observed that Formosa coal was only available locally, and Europeans bought it in Chinese ports, its origin unknown. “…now one has more certain knowledge, and yet we are still dealing with Keelung coal from Chinese port cities.”

Richthofen’s study of northern Taiwan’s geology noted that brown coal from Formosa could not compete with British hard coal — an enormous (by volume) and crucial export of the UK in the 19th century. Underappreciated today, British hard coal, preferred by steamship operators, was a dominant influence on geostrategy in the Far East during the colonial period.

Every nation that operated steamships in the Far East had to take its necessary presence into account in formulating military and economic strategy. Four decades of European and American interest in the coal mines around Keelung suggests that if Taiwan had possessed better-quality coal, it might have been annexed by one of those powers.

DREAMS OF FORMOSA

Back in Prussia, policymakers were thinking about Formosa. In April of 1861, a memorandum submitted to King William I recommended a Prussian naval base and settlement (for settlers and as a penal colony) on the island.

Though Richthofen recommended annexation, Eulenburg had soured on the idea. He told the Prussian government that the island lacked good harbors and that it was too hot and humid. He also pointed out to officials back in the capital that this would mean a break with other European countries and upset the treaties with China and Japan. Over the objections of the chief Admiral of the Prussian navy, who was quite taken with the idea of grabbing Formosa, the expedition was ordered home.

However, Formosa remained in the minds of Prussian diplomats and politicians. The Prussian victory over Austria in 1866 and the founding of the North German Confederation in 1867 led to public calls for the acquisition of colonies. In 1867, according to Becker, a German barrister called for the annexation of Formosa to become a German “Hong Kong.”

Becker notes that the Prussian consul to Japan, Max Brandt, who had been on the Eulenburg expedition, met with the King and the Crown Prince to discuss the annexation of Formosa. Though Brandt himself rejected the proposal, he felt that Germany needed a colony in the Far East to support its trade. The idea was dismissed as uneconomical.

The expanding French presence around Formosa, culminating in the French invasion during the Sino-French war of 1884-5, helped trigger another round of German involvement.

During the war, the French seized the port of Keelung but lacked the troops to grab the nearby coal mines, which remained in the hands of the Qing Dynasty.

The French chartered German merchant vessels to supply coal and other provisions to their positions in Keelung from Hong Kong (German vessels also ran munitions and troops up and down the China coast for the Qing).

A decade later, the first Sino-Japanese War (1894-95) made the German Kaiser Wilhelm II wistful with dreams of Formosa. He had persuaded himself that the British were about to grab Shanghai. If that happened, he wrote the German Chancellor in 1894, Germany should annex Formosa. “Speed is indicated,” he declared, “because, as I have heard confidentially, the French are already angling for Formosa.” A few days later the German envoy in Beijing suggested that Germany acquire the Pescadores (Penghu).

Germany had no naval base in Asia, and were dependent on Nagasaki and Hong Kong for repairs and coaling. Berths in the British colony had to be booked months in advance, a major issue for German naval influence in the Far East.

In 1895 a German navy analysis again suggested that Germany acquire a port. Among the options presented was seizing the Pescadores. The Japanese annexation of Taiwan ended that. In 1897, the Germans occupied Kiaochow (Jiazhou Bay 膠州灣) in Qingdao, and finally had their port.

Germany’s Formosa dreams highlight a simple fact of the 19th century: none of the imperialist powers, from Berlin to Beijing, considered that any territory they held was “integral” territory of their Empire. Imperial holdings were there to be seized from other powers, or traded back and forth to settle wars, tokens in the great game. The Qing demonstrated this: when they lost the war with Japan, they shrugged and gave Taiwan to Tokyo.

Reflect on that, the next time someone claims that Taiwan is an “integral” part of China.

Notes from Central Taiwan is a column written by long-term resident Michael Turton, who provides incisive commentary informed by three decades of living in and writing about his adoptive country. The views expressed here are his own.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Lines between cop and criminal get murky in Joe Carnahan’s The Rip, a crime thriller set across one foggy Miami night, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Damon and Affleck, of course, are so closely associated with Boston — most recently they produced the 2024 heist movie The Instigators there — that a detour to South Florida puts them, a little awkwardly, in an entirely different movie landscape. This is Miami Vice territory or Elmore Leonard Land, not Southie or The Town. In The Rip, they play Miami narcotics officers who come upon a cartel stash house that Lt. Dane Dumars (Damon)

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In