Alan Li no longer sees any future for his family in China after harsh COVID rules decimated his business, upended his son’s education and left his country out of step with the rest of the world.

He has given up hope of a return to normal after months of lockdowns in Shanghai, and now plans to close his firm and move to Hungary, where he sees better opportunities and his 13-year-old son can attend an international school.

“Our losses this year mean that it’s over for us,” he said wearily, asking to withhold his real name.

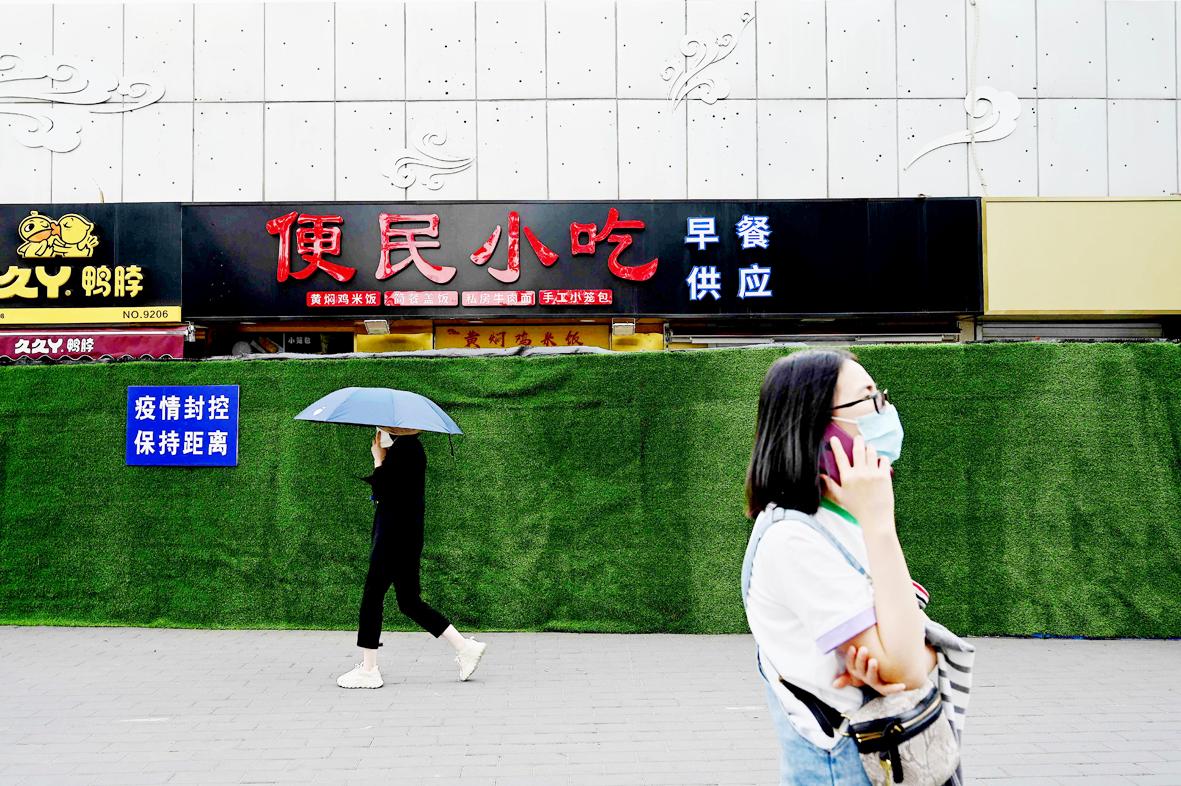

Photo: AFP

“We have been using our own cash savings to pay 400 workers (during the lockdown). What if it happens again this winter?”

Shanghai’s long shutdown, which brought food shortages and protests, has driven some to reconsider staying in a country where livelihoods and lifestyles can vanish at the whim of the state.

Schools have been closed and exams called off, including assessments for applying to American universities.

Photo: AFP

Li is frustrated that his son’s expensive bilingual schooling has been mostly online for two years, and he is anxious about the way Beijing has tightened oversight of the curriculum.

“This is a waste of our children’s youth,” Li said.

Being fairly well off, he has been able to take advantage of a European investment scheme that grants him and his family residency in Budapest.

“Many people know that if they sold all their assets they could ‘lie flat’ in a European country,” he said, using a slang phrase meaning to take it easy.

Beijing-based immigration consultant Guo Shize said his company has seen an explosion of inquiries since March, including a threefold increase in Shanghai clients.

Even after the lockdown eased, requests continued flooding in at more than double the usual level.

“Once that spark has been lit in people’s minds, it doesn’t die down quickly,” he said.

EXIT BAN

Censors have sought to suppress discussion of emigration, prompting nimble internet users to adopt the term “run” instead.

Searches for the term on messaging app WeChat peaked during Shanghai’s shutdown.

But as more people consider ways to leave, Beijing has doubled down on strict exit policies for Chinese citizens.

All “unnecessary” travel out of the country has been banned. Passport renewals have been all but halted, with authorities blaming the risk of COVID being carried into the country.

In the first half of last year, immigration authorities issued only two percent of the passports given out in the same period in 2019.

One woman who emigrated to Germany said she receives dozens of messages from Chinese people looking for tips on escaping.

Emily, who did not want to use her real name, tried to help a relative obtain a new passport to take up a job in Europe, but the application was denied.

“It’s like being a child who wants to go to their friend’s house to play but their parents won’t let them leave,” she said, adding that she has heard of passports being sold for up to 30,000 yuan (US$4,500) on the black market.

‘ABSOLUTELY INSANE’

A Chinese freelancer said he was turned back by immigration officers while attempting to fly to Turkey for work last October, despite having already checked in.

“My itinerary sounded too suspicious to them. They took my passport into an office and 15 minutes later told me I do not meet the requirements” for leaving, he said on condition of anonymity. “It was absolutely insane.”

He managed to leave weeks later by entering semi-autonomous Macau on a different travel document, before catching an onward flight.

Some are disillusioned with Beijing’s growing controls, which have been ramped up during the pandemic.

“I just want to live in a country where the government won’t crudely interfere in my personal life,” said Lucy, a 20-year-old student at an elite Beijing university involved in LGBTQ and Marxist activism.

The virus policies had “allowed the government to control and monitor everything”, she said.

“Perhaps rather than accepting and adapting to this system, we must go elsewhere and create a new life.”

Not long into Mistress Dispeller, a quietly jaw-dropping new documentary from director Elizabeth Lo, the film’s eponymous character lays out her thesis for ridding marriages of troublesome extra lovers. “When someone becomes a mistress,” she says, “it’s because they feel they don’t deserve complete love. She’s the one who needs our help the most.” Wang Zhenxi, a mistress dispeller based in north-central China’s Henan province, is one of a growing number of self-styled professionals who earn a living by intervening in people’s marriages — to “dispel” them of intruders. “I was looking for a love story set in China,” says Lo,

In the next few months tough decisions will need to be made by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) and their pan-blue allies in the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). It will reveal just how real their alliance is with actual power at stake. Party founder Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) faced these tough questions, which we explored in part one of this series, “Ko Wen-je, the KMT’s prickly ally,” (Aug. 16, page 12). Ko was open to cooperation, but on his terms. He openly fretted about being “swallowed up” by the KMT, and was keenly aware of the experience of the People’s First Party

It was on his honeymoon in Kuala Lumpur, looking out of his hotel window at the silvery points of the world’s tallest twin skyscrapers, that Frank decided it was time to become taller. He had recently confessed to his new wife how much his height had bothered him since he was a teenager. As a man dedicated to self-improvement, Frank wanted to take action. He picked up the phone, called a clinic in Turkey that specializes in leg lengthening surgery — and made a booking. “I had a lot of second thoughts — at the end of the day, someone’s going

Aug. 25 to Aug. 31 Although Mr. Lin (林) had been married to his Japanese wife for a decade, their union was never legally recognized — and even their daughter was officially deemed illegitimate. During the first half of Japanese rule in Taiwan, only marriages between Japanese men and Taiwanese women were valid, unless the Taiwanese husband formally joined a Japanese household. In 1920, Lin took his frustrations directly to the Ministry of Home Affairs: “Since Japan took possession of Taiwan, we have obeyed the government’s directives and committed ourselves to breaking old Qing-era customs. Yet ... our marriages remain unrecognized,