Between January and April, fake online lovers defrauded at least 415 people in Taiwan out of more than NT$73 million. And that’s just the reported cases, according to the Criminal Investigation Bureau (CBI).

Three near-misses made the news on consecutive days this week. On Monday, a Chiayi man tried to wire NT$300,000 to his “girlfriend,” who said she urgently needed the money to renovate her house, when he was stopped by post office staff, who notified the police. The man later said that he met her on a dating app, but never in person. He didn’t know her real name or what she looked like, but they would chat all day long.

The following day, the police stopped a 68-year-old Taoyuan woman from falling into a similar trap — she was about to wire NT$1 million to an “engineer” she met through Facebook who needed money to launch a business. They had never met in person.

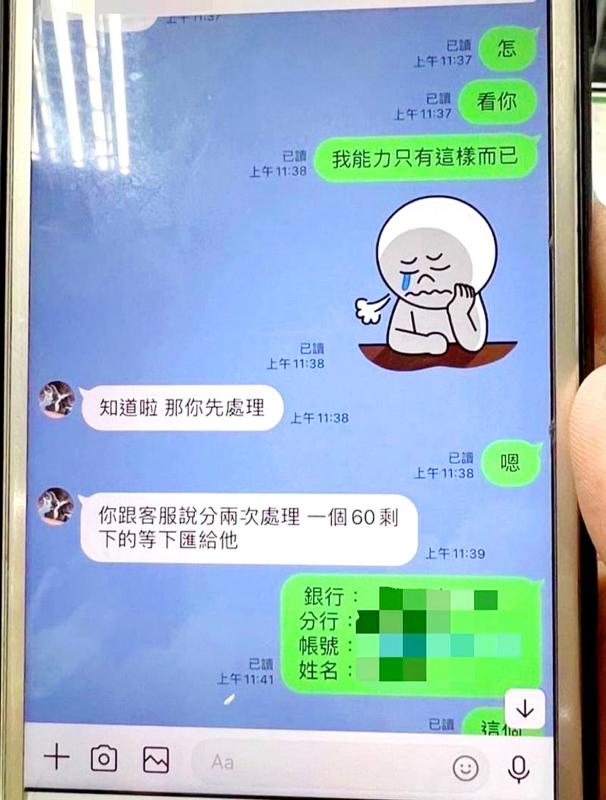

Photo: File photo

On Wednesday, a 36-year-old Taichung man nearly wired NT$850,000 to a Singaporean woman who told him she would help invest the money “for their shared future.” They had been communicating for less than a month.

According to the Liberty Times (the Taipei Times’ sister paper), victims often refuse to believe that they were victims of a scam. The paper reported at least nine other similar cases over the past month, and not all were able to retrieve their cash.

Dating scams are effective despite repeated public warnings by the police. The surge in the use of dating apps and social media have broadened the reach of scammers, yet “fake dating scam” only became a separate statistical category in 2019 with the National Police Agency.

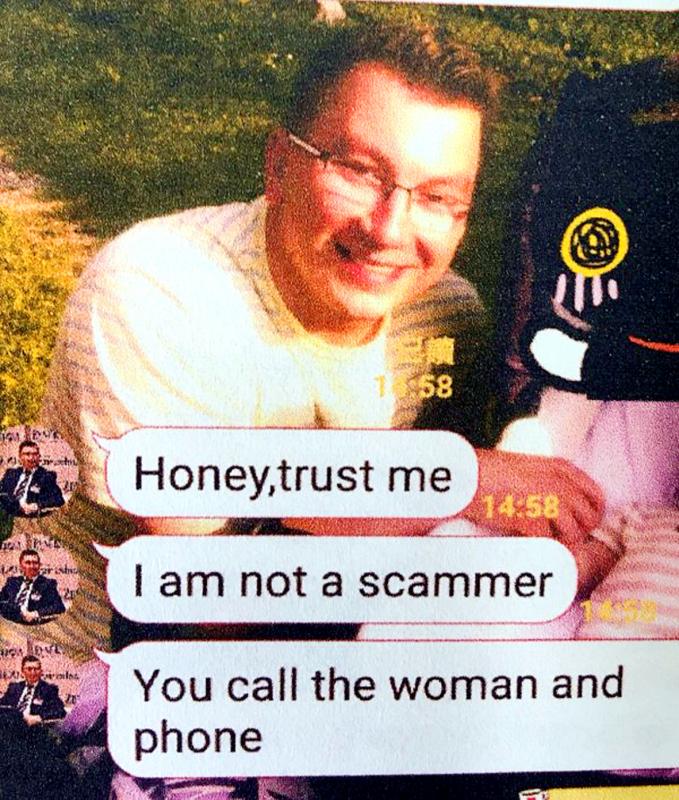

Photo: Hung Ting-hung, Taipei Times

That year saw 727 reported cases, compared to 1,174 last year. This year’s case numbers seem to be on pace to top that. The CBI has a catchy slogan to remind people to be vigilant: “meet up then talk, wire money no talk” (見面再談, 匯錢免談).

Romance scams are also on the rise in other countries. Reported losses in the US hit a record US$547 million last year, a nearly 80 percent increase from 2020, according to a Federal Trade Commission report. In Japan, inquiries to the National Consumer Affairs Center on investment scams related to dating sites grew from 84 in 2020 to 170 last year.

ELABORATE SCHEMES

Photo provided by victim

In more extreme cases, victims have become criminals too: last year, a Taipei bank teller surnamed Chen (陳) stole NT$9.81 million from her workplace to buy cryptocurrency for her online boyfriend who said he was in financial trouble. She also wired him her entire savings, leaving her with no money to post bail. Since she didn’t know the name or any other details of this man who vowed to “start a family” with her, there was no way to track him down and press charges.

It doesn’t have to be a dating app or site either. These people will find ways to strike up random conversations on social media or chat programs such as WhatsApp.

The schemes can get quite elaborate. In April, police arrested a man who had numerous cronies pretend to be women to chat with men online. They asked the men for gifts to “prove their love” before meeting up, then hired prostitutes go on dates with the men (and get more money out of them by faking emergencies or debt). As things got more serious, the scammers’ fake “mother” would appear to discuss marriage payments and so on. This group swindled millions of dollars out of more than 10 victims.

While the majority of victims are male, a particular tactic targeting women is pretending to be some sort of foreign bigwig — often in a troubled country — who desperately needs help, not unlike the ageless “Nigerian Prince” scam.

In the study “It turned out to be nothing at all: Research on the Victimization Process of Online Romance Scam” (竟是一場空: 網路愛情詐騙被害歷程之研究), Chih Chin-wei (池晉煒) interviewed five middle-aged female victims who lost a total of NT$48.5 million between 2019 and last year.

One woman in the study fell for a man who randomly added her on Facebook and claimed to be a Chinese-American doctor working in a Syrian refugee camp. He wooed her for about three months, and once they confirmed their relationship, he began using all sorts of bogus reasons to ask for money: his life was in danger due to a dangerous mission; he needed a private flight to rescue his commander; his commander’s daughter needed surgery; he needed surgery. He also promised to pay her back and come to Taiwan and marry her.

In an effort to maintain her trust, the man told her that he was returning some of her money. It never arrived. Her friends tried, unsuccessfully, to stop her from sending him more. It was only when one of her daughters — a policewoman — proved that the accounts were fake that she stopped sending him money. In the end, she lost more than NT$15 million.

REHASHING OLD TRICKS

With today’s technology, scammers don’t need to directly ask for money. All they need is personal information.

Yet the painfully obvious old methods still work. On New Year’s Day, a man was excited to finally meet his online girlfriend for dinner — but she asked him to spend NT$5,000 on a “meeting guarantee fee.”

Also increasingly common is the scam where a virtual girlfriend announces that she can no longer use LINE because she’s moving to China (among other excuses) and suggests a shady app that requires all sorts of fees to use. One man lost NT$1.25 million this way last month.

Even traditional dating services aren’t safe. There were nearly 500 complaints of fraud filed last year, mostly involving exorbitant fees for meet-up events or VIP accounts, and signing unsecured loan agreements that resulted in massive debt.

Plenty of Web sites provide tips for avoiding fraud: Avoid those who keep bringing up their hardships, and those who seem overly eager, and those who find excuses not to meet face to face, and those who quickly start discussing long-term plans and those who claim to be investment experts. The list goes on.

Liu Yen-po (劉彥柏), who runs the “Scam Prevention Expert” (防詐達人) service for anti-virus company Trend Micro, told CommonWealth Magazine (天下) in a recent podcast: “The trickiest part of dating fraud is that through [daily interaction], the victims have already invested much time, emotion and other sunk costs. Once you are invested emotionally, not even technology can save you.”

Liu says the first step is to stay alert and insist on meeting the other person, especially before sending them money.

“Most scammers will find it cumbersome and are more likely to give up,” Liu said.

In real life, people will usually take their time knowing someone before getting serious, but it seems to be the opposite on the Internet as they project their ideals onto this virtual person. And once they bring up money, be on high alert: investigate as much as possible their online presence.

If you think you are a victim of a romance scam, contact the government’s anti-fraud 165 hotline.

The Taipei Times last week reported that the rising share of seniors in the population is reshaping the nation’s housing markets. According to data from the Ministry of the Interior, about 850,000 residences were occupied by elderly people in the first quarter, including 655,000 that housed only one resident. H&B Realty chief researcher Jessica Hsu (徐佳馨), quoted in the article, said that there is rising demand for elderly-friendly housing, including units with elevators, barrier-free layouts and proximity to healthcare services. Hsu and others cited in the article highlighted the changing family residential dynamics, as children no longer live with parents,

It is jarring how differently Taiwan’s politics is portrayed in the international press compared to the local Chinese-language press. Viewed from abroad, Taiwan is seen as a geopolitical hotspot, or “The Most Dangerous Place on Earth,” as the Economist once blazoned across their cover. Meanwhile, tasked with facing down those existential threats, Taiwan’s leaders are dying their hair pink. These include former president Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文), Vice President Hsiao Bi-khim (蕭美琴) and Kaohsiung Mayor Chen Chi-mai (陳其邁), among others. They are demonstrating what big fans they are of South Korean K-pop sensations Blackpink ahead of their concerts this weekend in Kaohsiung.

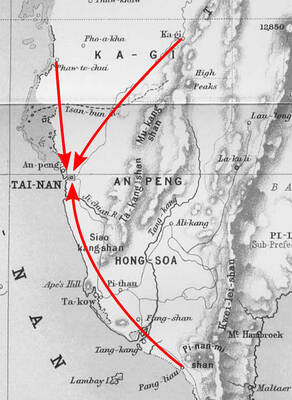

Oct 20 to Oct 26 After a day of fighting, the Japanese Army’s Second Division was resting when a curious delegation of two Scotsmen and 19 Taiwanese approached their camp. It was Oct. 20, 1895, and the troops had reached Taiye Village (太爺庄) in today’s Hunei District (湖內), Kaohsiung, just 10km away from their final target of Tainan. Led by Presbyterian missionaries Thomas Barclay and Duncan Ferguson, the group informed the Japanese that resistance leader Liu Yung-fu (劉永福) had fled to China the previous night, leaving his Black Flag Army fighters behind and the city in chaos. On behalf of the

I was 10 when I read an article in the local paper about the Air Guitar World Championships, which take place every year in my home town of Oulu, Finland. My parents had helped out at the very first contest back in 1996 — my mum gave out fliers, my dad sorted the music. Since then, national championships have been held all across the world, with the winners assembling in Oulu every summer. At the time, I asked my parents if I could compete. At first they were hesitant; the event was in a bar, and there would be a lot