May 30 to June 5

Nearly four decades before “Made in Taiwan” became a global phenomenon in the 1970s, renowned artist Yen Shui-long (顏水龍) launched a one-man mission to bring local products to the international stage.

“I want the world to see how useful Taiwanese products are, and overturn the current situation where the notion of ‘Made in Taiwan’ is frowned upon,” Yen wrote in a 1942 op-ed in the Public Opinion Press (公論報).

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Historica

Not only did he feel that local crafts were overlooked by the Japanese authorities, he wanted to bring the arts closer to the people through a “crafts revival” of everyday objects.

“I hope to awaken the average person’s appreciation toward these crafts, and revolutionize their production strategies. If in the near future, Taiwan’s products can truly shine in the global market, I will be more than pleased!”

However, his peers in the fine art world scoffed at the idea, and while the authorities were somewhat receptive, Yen’s plans to set up a crafts school and center were cut short by World War II. He continued the effort to, again, lukewarm support under the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), and in a 1978 article he lamented that most people still focused on material wealth and ignored taste and quality of life — much less appreciate the arts.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Yen’s efforts were not for naught, however, as he published several valuable compendiums and inspired numerous students to carry on his mantle. Today, he’s honored as the “father of modern Taiwanese crafts,” and is noted for his particular interest in indigenous artistry.

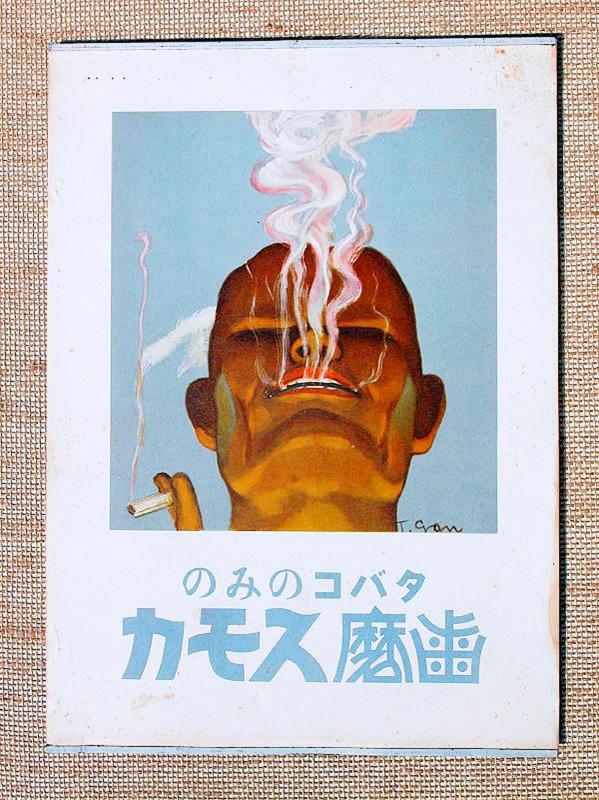

Yen was also the first Taiwanese to work as an commercial illustrator, creating numerous pieces for Japan’s Smoca tooth powder company between 1933 and 1940, which can be seen in the book, Taiwan’s First Ad Man: Yen Shui-long (台灣第一廣告人:顏水龍).

FIRST AD DESIGNER

Photo: Chen Feng-li, Taipei Times

Although Yen was born to a well-off family on June 5, 1903 in Tainan’s Hongmaocuo Village (紅毛厝), he had a tragic upbringing. His parents died when he was young, and with his grandmother’s death and elder sister’s marriage when he was 13, he was left to raise himself alone.

Yen started training to become a schoolteacher that same year, and at age 15 he was hired as the youngest instructor at the public elementary school in today’s Siaying (下營) District. A Japanese colleague noticed Yen’s talent for art, and encouraged him to study in Japan. Yen enrolled in a Japanese high school in 1920 and was accepted to the Tokyo School of Fine Arts two years later, working side jobs to make ends meet.

His talent began to shine after he entered the school’s master’s program in 1927. With other notable Taiwanese classmates such as Chen Cheng-po (陳澄波) and Liao Chi-chun (廖繼春), Yen formed the Akajima Art Group (赤島社) and was selected to exhibitions in Japan and Taiwan. With financial support from Lin Hsien-tang (林獻堂) of the Wufeng Lin Family (霧峰林家), Yen was able to further his talent in Paris, where two of his paintings were selected to the prestigious Salon d’Automne in 1931

Photo: Chang Hsuan-che, Taipei Times

A year later, Yen was forced to return home due to a liver ailment that depleted his funds. Unable to find meaningful work in Taiwan, he signed on as an commercial artist for a wine company in Osaka. He was soon recruited by Smoca’s head of advertising, Toshiro Kataoka, who one day asked his opinion on ad design while they were having coffee. Yen was shocked as Smoca employed several well-known Japanese illustrators.

“I nervously told them that I felt that newspaper layouts were usually very complex, therefore it was imperative to leave white space in the advertisements,” he writes. “The white space should contain just a small image with simple lines and a few sentences, along with a consistent Smoca logo.”

Smoca brought him on a few months later.

WARTIME ENDEAVOR

Unlike his peers, Yen wasn’t as interested in making a name as a painter — he only held five exhibitions over a career spanning 76 years.

He recalls in the 1978 article telling a reporter during a show in the 1930s that most Taiwanese lack an understanding of art, to which the reporter responded: “Before you want people to understand something, you must enlighten them first.”

This exchange inspired him to use his talent to better people’s lives, and during his time in Japan he began thinking of how to systemize the production of Taiwan’s folk crafts and market them to the world. Not only would the endeavor help preserve these traditions in a modernizing society, it could improve the standard of living for ordinary Taiwanese and also enrich their aesthetic appreciation. He began by traveling in Japan and observing craft schools and workshops, hoping to replicate their success in Taiwan.

Starting around 1936, Yen made frequent trips home despite the war heating up, traversing the countryside and documenting the various everyday crafts he encountered.

With no local support and minimal funding from the government, Yen set up a rush weaving cooperative that enjoyed moderate success, exporting bags, sandals and doormats to Japan and China. He also established a bamboo working studio, but it was destroyed in an air raid. In 1943, he accompanied Japanese folk craft movement pioneer Soetsu Yanagi on a tour of Taiwan, and was glad that Yanagi approved of the works they saw.

PUBLIC ARTIST

Yen continued his efforts after the war, but he was again faced with a lack of resources. Although the authorities hired him as a handicrafts consultant, they didn’t give him enough money to keep his workshop and research center in Nantou afloat, and it closed in 1958.

However, through the center and teaching at various schools, he trained numerous future craftworkers and experts, establishing a solid foundation for the industry’s future.

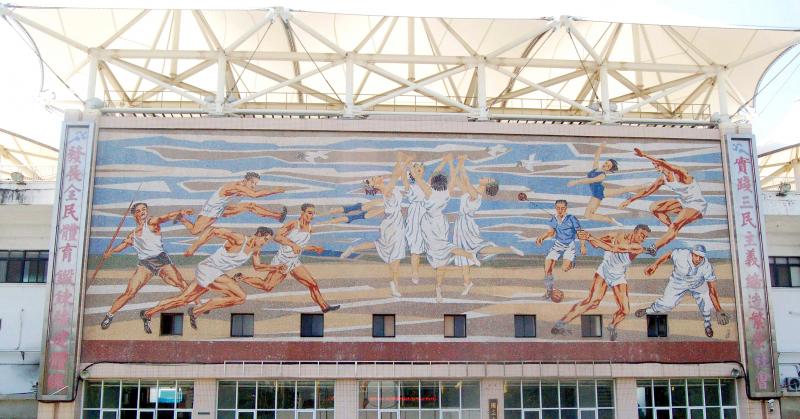

During the 1960s, Yen was involved in numerous public art and urban beautification projects in Taipei, including Jiantan Park, the outdoor spaces around Zhongshan Hall and Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall and the entrance to Ziqiang Tunnel (自強隧道). He retired at the age of 84, but continued to travel and make art until his death in 1997.

Perhaps the project that exemplified his ideals was the Taiyang Tang Bakery (太陽堂) in Taichung, which opened in 1964. He handled all the aesthetics including the architecture, interior design and product packaging, incorporating traditional crafts and motifs and creating a large sunflower mosaic as the store’s “crown jewel.”

Unfortunately, government censors inexplicably decided that the sun and sunflower symbols referenced the Chinese communist anthem The East is Red (東方紅), and the mosaic was covered up until after the lifting of martial law in 1987.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.