May 16 to May 22

Lin Wen-cha (林文察) and his “Taiwanese braves” (台灣勇) arrived in Fujian Province’s Jianyang District (建陽) on May 19, 1859, eager for their first action outside of Taiwan.

The target was local bandit Guo Wanzong (郭萬淙), one of several ruffians who had taken advantage of ongoing Taiping Rebellion to establish strongholds in the area.

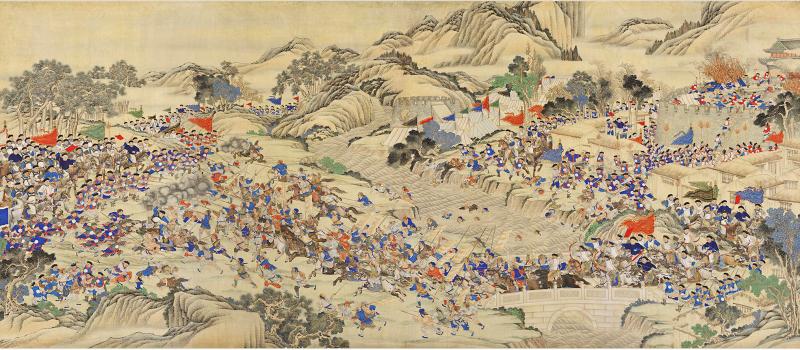

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

A strongman leader of the notable Wufeng Lin Family (霧峰林家), Lin had impressed Qing Dynasty rulers five years earlier by helping expel the remnants of Small Knife Society (小刀會) rebels from Keelung.

Lin’s forces routed Guo’s gang in just 11 days, earning a formal military position and the heroic title “baturu.” Hsu Hsueh-chi (許雪姬) writes in the Lin Wen-cha and the Taiwan braves — a preliminary study on Taiwan Braves deployed to the mainland (林文察與台勇 — 台勇內調出探) that this was the first time Taiwanese fighters were summoned to China.

The Qing Dynasty needed them because they were preoccupied with the Taiping rebellion. Additionally, Lin’s fighters were skilled and experienced as they were constantly clashing with rival Han clans and indigenous warriors back home. They were also familiar with mountainous warfare, which proved beneficial in Fujian.

Photo courtesy of Taichung City Government

Lin fought numerous battles for the Qing Dynasty on both sides of the Taiwan Strait over the next five years, finally falling against a Taiping army in December 1864. He was only 36. He was posthumously elevated to general — the second highest rank ever achieved by a Taiwanese during Qing rule.

LOCAL STRONGMEN

As Hsu Hsueh-chi writes in Lin Wen-cha and the Taiwan braves, the word yong (勇, “braves”) generally referred to irregular troops who fought for the Qing.

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

They were not heavily used until the Lin Shuang-wen (林爽文) rebellion of 1768 in Taiwan. With the Qing forces unable to gain the upper hand, commander Fukanggan (福康安) recruited local braves to help with the effort.

Lin Wen-cha was a fifth-generation descendent of Lin Shih (林石), who crossed the Taiwan Strait in 1746 and settled in the Changhua area. The family pushed into Wufeng (霧峰) as more settlers arrived, and in this chaotic atmosphere, “communal and clan groups rallied around vigorous leaders, assertive and skilled in combat … Known as local strongmen (土豪), they formed an alternate, if unstable, system of power, superseding the city-based magistrates and their representatives as de-facto power holders,” writes Johanna Menzel Meskill in A Chinese Pioneer Family: The Lins of Wufeng, Taiwan.

Lin Wen-cha’s father, Lin Ting-pang (林定邦), was one of these strongmen who employed a small force of braves. When Lin Ting-pang was killed by rival strongman Lin Ma-sheng (林媽盛) in 1848 over a land dispute, Lin Wen-cha took things into his own hands after the authorities failed to respond. After nearly three years of violent clashes, he captured Lin Ma-sheng and personally killed him in front of his father’s grave with his clansmen and neighbors watching.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Lin Wen-cha turned himself in, but he was never tried. This move was of political significance, showing that he was willing to expand his power base “by working with, rather than against the authorities,” Meskill writes. This stance was to define the Lin family’s relationship with subsequent rulers — although by the time the Japanese arrived in 1895 they had reinvented themselves as a wealthy and educated clan who loved the arts and not fighting.

RISING STAR

Lin’s power grew, personally fighting in several campaigns in Taiwan with a force of nearly 1,000 braves. After his successful first venture in Fujian, he traveled north to Zhejiang to take on the Taiping rebels. He and his men joined the 20,000-strong Min Army (閩軍), where he served as a senior commander, and in 1862 was promoted to provincial commander-in-chief.

While Lin was busy chasing down rebels in Zhejiang, the Tai Chao-chun (戴潮春) rebellion broke out near his home village. The rebels, including Lin Jih-cheng (林日成) and the Hung (洪) clan, were mostly sworn enemies of the Wufeng Lin family, and they saw it as a chance to settle old scores.

Lin Jih-cheng’s forces besieged Wufeng, which was severely weakened since many able-bodied men were fighting with Lin Wen-cha in Zhejiang. The Wufeng Lins held out, however, and with the help of Hakka and Qing reinforcements, they drove off the rebels.

Lin Wen-cha returned home in the fall of 1863 with Ting Yue-chien (丁曰健), who previously held several official positions in Taiwan. They used their clout to bolster their forces, and Lin took Douliou while Ting seized Changhua. The two commanders disagreed on the next step and acted independently, and Ting caught Tai within a few weeks.

Lin Wen-cha turned his attention to Lin Jih-cheng, a victory he needed since Ting got to Tai first, and he also wanted to avenge the siege on his village. After a three-week standoff in Lin’s home village of Sikuaicuo (四塊厝), he captured Lin Jih-cheng and had him dismembered.

ROYAL REWARDS

Lin Wen-cha and Ting continued feuding, however. The wily Ting gained the upper hand and leveled several accusations against Lin and his family. Lin was initially unwilling to return to Fujian despite the Qing court’s orders, but he was forced to leave in September 1864.

After the fall of their capital in Nanjing, the Taiping rebels had fled to Fujian en masse and seized several county seats. The Qing agreed to absolve Lin of all his alleged transgressions if he was able to take care of the rebels, and Lin set out for his final battle.

His new troops were not as valiant or united as the Taiwanese braves he left behind, Meskill writes, and the outnumbered unit was routed in December 1864.

Hsu writes that even though he failed, Lin was given a slew of posthumous honors, including a hereditary rank that was passed on to his son, Lin Chao-tung (林朝棟). The family was also granted monopoly over the camphor trade in Fujian Province (which included Taiwan). Coupled with properties questionably acquired during Tai’s rebellion, the Lins were on their way to becoming one of the wealthiest in Taiwan.

However, Lin’s lingering quarrels with Ting, as well as bad relationships with his neighbors, continued to cause considerable chaos and legal problems for the family until things were finally settled in the early 1880s.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

In the American west, “it is said, water flows upwards towards money,” wrote Marc Reisner in one of the most compelling books on public policy ever written, Cadillac Desert. As Americans failed to overcome the West’s water scarcity with hard work and private capital, the Federal government came to the rescue. As Reisner describes: “the American West quietly became the first and most durable example of the modern welfare state.” In Taiwan, the money toward which water flows upwards is the high tech industry, particularly the chip powerhouse Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電). Typically articles on TSMC’s water demand

Every now and then, even hardcore hikers like to sleep in, leave the heavy gear at home and just enjoy a relaxed half-day stroll in the mountains: no cold, no steep uphills, no pressure to walk a certain distance in a day. In the winter, the mild climate and lower elevations of the forests in Taiwan’s far south offer a number of easy escapes like this. A prime example is the river above Mudan Reservoir (牡丹水庫): with shallow water, gentle current, abundant wildlife and a complete lack of tourists, this walk is accessible to nearly everyone but still feels quite remote.