When Dongi Kacaw was asked to write three articles about indigenous wild greens 26 years ago, she responded with surprise.

“I don’t know how to do that,” she says. “I just know how to eat them!”

But after returning to Hualien, the indigenous Pangcah (Amis) now known as the “godmother of wild greens” (野菜教母) could not stop thinking about the request. She couldn’t find anything in the library about the plants she grew up with — so she went home to ask her parents.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

“I started taking photos, visiting sunset markets, going foraging with old people … I completely threw myself into the project like a madwoman,” Dongi says.

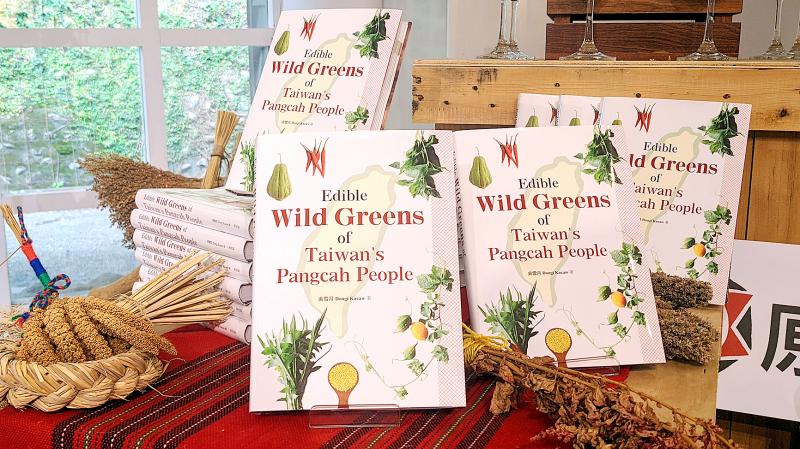

She ended up submitting 36 articles to Taiwan Indigenous Voice Bimonthly (山海文化), which became the basis for her 2000 book, Edible Wild Greens of Taiwan’s Pangcah People (台灣新野菜主義). It was unexpectedly popular, and was reprinted 18 times and translated into the Pangcah language last year. On Tuesday, the English-language version of the book was released at the Hualien Indigenous Wild Vegetables Center (花蓮原住民族野菜學校), where Dongi is the principal.

Edible Wild Greens features 63 local entries organized by parts of the plant, as well as six contributions from Hawaii, Indonesia and India that were not included in previous editions.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

“The purpose of this book is not only to impress on people how many types of edible plants there are in the world, but also to explain, from the perspective of the wild greens culture of the Amis community, the importance of wild plants to our lives,” the book’s introduction states.

Dongi hopes that the book will help facilitate more international exchanges on traditional food culture during events such as the Austronesian Forum and the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues.

“We share many similar food items with other Austronesian and Southeast Asian peoples, but we may use them differently,” Dongi says. “We can show them how we forage, and then we can exchange and generate new ideas.”

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

FIELDS AND MOUNTAINS OF EDIBLE GREENS

Despite being best known for her work in studying, promoting and preserving her people’s wild greens, most visitors enthusiastically greet Dongi as jiaoguan (教官, military instructor), referring to the retired lieutenant colonel’s old job at National Hualien University of Education.

“When we Pangcah people look at plants, we always first identify which part is edible,” Dongi says. “We’re the most prolific at eating wild greens in Taiwan. There are fields and mountains full of edible plants here, but most people don’t know about them.”

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

If the Pangcah are unsure about a plant, they’ll pick a tender leaf and lick it with the tip of their tongue.

“If there’s no numbing or tingling feeling, then it’s a wild green,” she says.

Today, Dongi runs a wild vegetable center, which opened in December 2020 with government support. It hosts exhibitions, tours and workshops that promote these plants, with the goal of preserving indigenous biodiversity. Many wild plants she ate as a child have disappeared, and for the past decade she’s been trying to restore them and preserve the seeds.

Photo courtesy of Hualien County Government

She’s also led a number of international exchanges as head of the Taiwan indigenous people’s chapter of the Italy-based Slow Food International, which aims to prevent the disappearance of local food cultures and traditions and promote “good, clean and fair” eating. They’ve participated in numerous events abroad, and also host an annual international indigenous slow food forum in Hualien.

As Taiwan’s indigenous people interact more with the rest of the world, especially with their Austronesian relatives and other indigenous groups, it became increasingly crucial to translate Edible Wild Greens of Taiwan’s Pangcah People into English.

TRANSLATOR NOTES

Cheryl Robbins, a licensed tour guide whose work includes the Foreigner’s Travel Guide to Taiwan’s Indigenous Areas series, says she offered to translate the book after seeing Dongi give the Chinese version of the book to several Maori visitors from New Zealand a few years ago.

She credits book editor (and Taipei Times contributor) Steven Crook for alerting her to areas that needed further clarification and elaboration.

“The reader may not have that much experience in indigenous communities,” says Robbins, who has been working with indigenous communities for decades. “[Crook] was good at pointing out when I needed more information and when I needed to simplify and clarify.”

Robbins, whose background is in zoology, was worried that her lack of familiarity with botany would be a challenge, but besides a brief scientific introduction to start each entry, she found the prose quite conversational.

“[Dongi] talks about how her mother and grandmother used [a plant], or that they went to someone’s house and cooked it a certain way,” Robbins says. “It’s tied to her experience growing up in an Amis community, and during that time Taiwan was not very economically well off, so wild greens really did play an important part in their diet.”

Robbins hopes that Dongi continues to produce material in English, and even offer activities and classes in the language.

“She’s a national treasure in terms of her knowledge of wild greens,” she says. “I hope this will be a good first step toward being able to share more of this knowledge not just with indigenous people, but people from various cultures, countries and backgrounds.”

NEW EDITION?

Dongi is already thinking of revising the book, as much has changed for her in the past 22 years. She wanted a more extensive international section in this latest release, but she says she had a hard time finding writers within a short time frame.

“I also didn’t think about the deeper cultural implications when I wrote the stories,” she says.

She’s pondering how to rearrange the book according to the Pangcah knowledge system to “reclaim our food sovereignty,” although she hasn’t entirely figured out how.

“Why do we have to follow the scholarly categorizations of roots, stems, leaves, flowers and fruits?” she asks. “Our people classify some plants according to their taste. We need to quickly sort out and systematize this knowledge.”

Dongi also hopes to include recipes in the book.

There are still some lingering issues with indigenous foodways that Dongi hopes to address. Only in 2019 was the Forestry Act (森林法) amended to allow indigenous people to collect forest resources on public land for personal use without worrying about being arrested.

“We had to covertly harvest yellow rotang palms for their hearts before,” she says. “How can a Pangcah not forage for wild greens?”

She also spoke emotionally about the restrictions on private alcohol brewing.

“This is our culture, our way of life. We have to work hard to change this situation.”

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

Lines between cop and criminal get murky in Joe Carnahan’s The Rip, a crime thriller set across one foggy Miami night, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Damon and Affleck, of course, are so closely associated with Boston — most recently they produced the 2024 heist movie The Instigators there — that a detour to South Florida puts them, a little awkwardly, in an entirely different movie landscape. This is Miami Vice territory or Elmore Leonard Land, not Southie or The Town. In The Rip, they play Miami narcotics officers who come upon a cartel stash house that Lt. Dane Dumars (Damon)