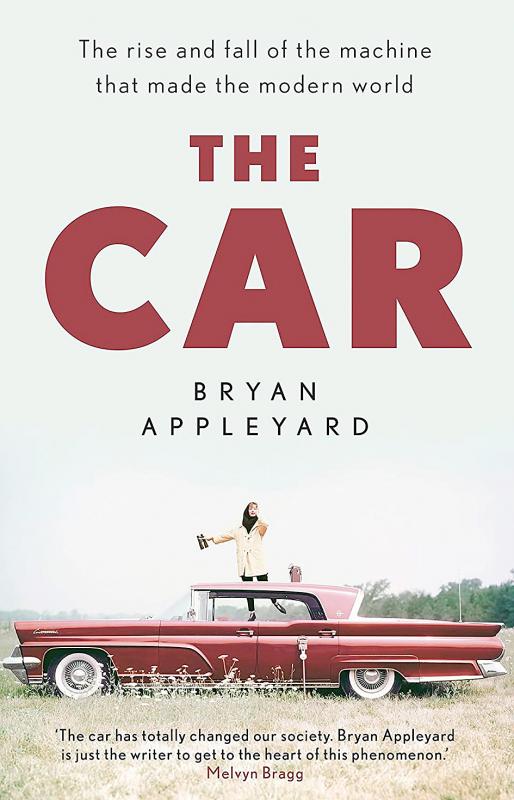

“Within a few years owning a car,” writes Bryan Appleyard in this entertainingly forthright history, “might seem as eccentric as owning a train or a bus. Or perhaps it will simply be illegal.”

Although Appleyard’s intention is to document a way of life that he believes is passing, his book is not a lament or a eulogy, nor really a celebration, but instead an acknowledgment of the extraordinary cultural and environmental impact the car has had on this planet in the last 135-plus years.

We have shaped our lives, our cities, our worlds around the needs and possibilities of internal combustion engine vehicles. And nowhere has this global trend been more conspicuously evident than in the US, a nation whose rise, supremacy and incipient decline closely match the fortunes of the motorcar.

In a book that almost delights in the contradictions wreaked by the automobile, one of the more glaring paradoxes is that while the author focuses on America, he is no fan of the cars it has produced — with very few exceptions.

With that discrimination established, it is thankfully not a work specifically aimed at petrolheads and is thus largely free of discussions of camshafts and torque. Instead Appleyard approaches cars through the people who made them — not the assembly-line workers, but the factory owners and designers.

After a few preliminaries, the story really begins with two contrasting, though equally paradoxical, figures: Henry Ford and Alfred Sloan. The men behind Ford and General Motors, for much of the 20th century they presided over the two biggest car manufacturers in the world. Ford was an unpredictable, idiosyncratic visionary who brought all his considerable energy to bear on producing the most utilitarian car imaginable: the Model T.

Sloan was a far less colorful — almost faceless — businessman whose success was based on diversification, imaginative marketing and stylistic flourishes. It was as if their insights were the opposite of their characters.

Yet despite their different approaches, Ford and GM were equally complacent when it came to foreign competition. For several decades, their shared sense of superiority was understandable. Despite producing some wonderful cars, European manufacturers never made much headway in the American market.

It’s sobering to be reminded that in 1932 Britain was the world’s largest car manufacturer and by the 1950s was the world’s biggest car exporter. But for all its engineering strengths, the UK failed to invest and innovate in manufacturing processes and became increasingly subject to disastrous industrial action.

While Germany fared much better, as Volkswagen cornered the small car market, and BMW, Audi and Mercedes dominated the executive end, it was Japan that revolutionized car manufacturing. In the process it left Detroit — Motor City itself — fighting for its life.

As sharply as he draws portraits of the key players, Appleyard, one of the liveliest minds in journalism, is at his most acute when musing on the cultural effects of the car. When four wheels replaced the horse as the main mode of transport, people were still severely restricted in their movements.

Particularly in America, the world beyond major cities was not easily accessible. Paved road systems changed that. The roads were paved because that’s what cars required and, equally, cars were built to fill the paved roads. All of this circular activity brought city dwellers into contact with the great outdoors, the “unspoilt” wilderness beyond city limits.

But of course the building of roads, and the cars they bore, encroached on the wilderness, spoiling the very nature that drivers and their passengers wanted to savor. Part of the automobile’s attraction was the autonomy it offered to individuals, the sense of freedom of movement, of personal liberty, a freedom whose cost we are only now really counting.

This is the strange mental condition that the car helps foster, an idea of individual liberty that is curtailed only by others, never ourselves; it’s why we see traffic jams as something thrust upon us, rather than a whole of which we form an active part. Another way that cars have affected our sense of space is in the emotional draw of imagined destinations — the existential lure of the road trip.

Somewhere out there, cars seem to suggest, is an authentic reality that, if we could only drive for long enough, we could find. As Appleyard wryly observes: “There is a popular conviction, first, that America in particular is a country that needs looking for and, second, that it cannot be found.”

Appleyard has plenty more zingers where that one came from. In the first half of the book, they help animate a fast-moving narrative of industrial development, but in the second half they’re more often employed to disguise the fact that the story has run out of road. So economically and brightly does Appleyard establish the main plot points of the automobile’s progress and then crisis that after the halfway point he is increasingly reliant on revisiting popular culture to make his invariably witty points.

Perhaps the car’s gradual automated demise is too dull and unromantic to engage his creative imagination. Or maybe pondering the meaning of celebrity car deaths or commenting on the inefficacy of drive-by shootings is just more engaging than considering the algorithm-shaped future.

Weighing up the ecstatic freedoms and the remarkable convenience the car has brought against the death and destruction it has also delivered, Appleyard finishes on a note of anticipated nostalgia. All the many driven car designers and manufacturers, he concludes, “made a way of life that was worth living.”

April 28 to May 4 During the Japanese colonial era, a city’s “first” high school typically served Japanese students, while Taiwanese attended the “second” high school. Only in Taichung was this reversed. That’s because when Taichung First High School opened its doors on May 1, 1915 to serve Taiwanese students who were previously barred from secondary education, it was the only high school in town. Former principal Hideo Azukisawa threatened to quit when the government in 1922 attempted to transfer the “first” designation to a new local high school for Japanese students, leading to this unusual situation. Prior to the Taichung First

The Ministry of Education last month proposed a nationwide ban on mobile devices in schools, aiming to curb concerns over student phone addiction. Under the revised regulation, which will take effect in August, teachers and schools will be required to collect mobile devices — including phones, laptops and wearables devices — for safekeeping during school hours, unless they are being used for educational purposes. For Chang Fong-ching (張鳳琴), the ban will have a positive impact. “It’s a good move,” says the professor in the department of

On April 17, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) launched a bold campaign to revive and revitalize the KMT base by calling for an impromptu rally at the Taipei prosecutor’s offices to protest recent arrests of KMT recall campaigners over allegations of forgery and fraud involving signatures of dead voters. The protest had no time to apply for permits and was illegal, but that played into the sense of opposition grievance at alleged weaponization of the judiciary by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) to “annihilate” the opposition parties. Blamed for faltering recall campaigns and faced with a KMT chair

Article 2 of the Additional Articles of the Constitution of the Republic of China (中華民國憲法增修條文) stipulates that upon a vote of no confidence in the premier, the president can dissolve the legislature within 10 days. If the legislature is dissolved, a new legislative election must be held within 60 days, and the legislators’ terms will then be reckoned from that election. Two weeks ago Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (蔣萬安) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) proposed that the legislature hold a vote of no confidence in the premier and dare the president to dissolve the legislature. The legislature is currently controlled