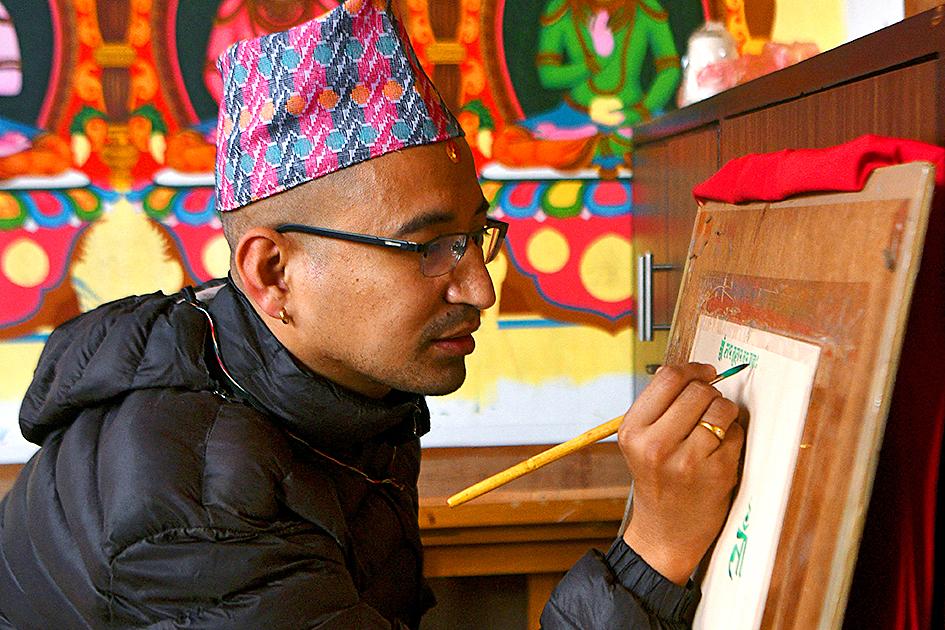

With a shaved head and an empty stomach, artist Ujay Bajracharya dips his brush to line the eyes of the deity Tara as a soothing Buddhist hymn warbles in the background.

The 40-year-old is applying the final strokes to his paubha painting, a devotional art form known for its minute detail, intense colors and the strict purification rituals traditionally required of its practitioners. It took three months for Bajracharya to complete his rendition of the Green Tara, a goddess of compassion revered by Buddhists and Hindus in Nepal.

Before work began, he shaved off his hair and clipped his nails, while a Buddhist priest blessed his canvas and selected a day auspicious enough for the artist to commence his labors.

Photo: AFP

Bajracharya woke up early each morning and did not eat until his day’s work was over, adopting a strict vegetarian diet that also excluded garlic, tomatoes and onion when he broke his fast.

“My body felt light and I felt more focused and motivated to paint,” he said. “Changing my lifestyle was a bit difficult at first but I had the support of my family and friends, so that helped me stay disciplined.”

Paubha remains a common painting method in Nepal but the austere religious observances once followed by its artists have fallen out of practice.

Photo: AFP

Bajracharya’s adoption of these rituals began last year, when he approached a museum in the capital Kathmandu about painting another Buddhist deity while adhering to the forgotten traditions.

Rajan Shakya, founder of the Museum of Nepali Art, said that they immediately agreed to the idea of reviving the practice.

“It is part of what makes paubha art unique and valuable. The more people learn about it, the more demand there will be for Nepali artists. And then we know our art will survive, our culture will survive,” Shakya said.

Photo: AFP

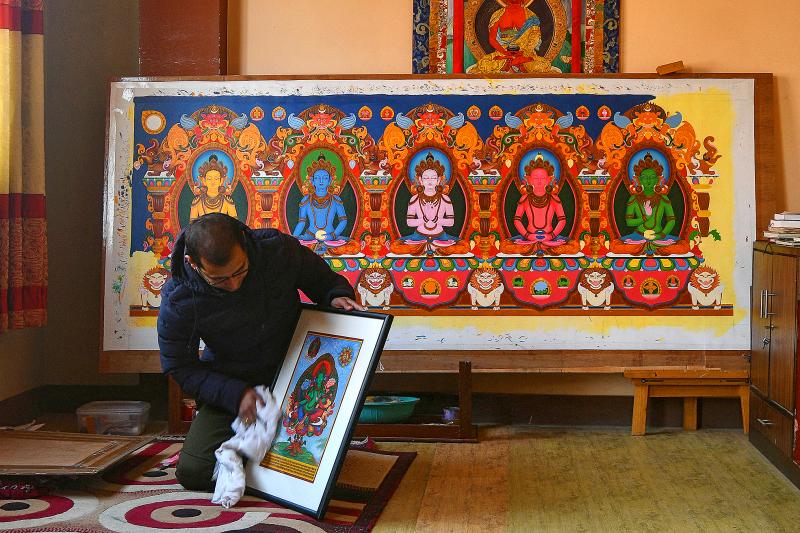

Bajracharya has committed to observing these rules for future paintings, beginning with his exacting work on the Green Tara, which he crafted for worship in a private prayer room at his home.

“I felt that we should preserve this method and the next generation should also be aware — people should know about the spiritual aspect of these paintings,” he said.

Paubha artworks use cotton or silk canvases, and colors were traditionally made by grinding minerals and plants into fine powder. Some works even used pure gold and silver.

The oldest preserved paubha painting dates to the 13th century, but scholars believe the tradition is much older, with earlier examples likely disappearing because of the fragile materials used.

Its artists are believed to have inspired trends in thangkas, a similar type of devotional painting in neighboring Tibet that has been recognized in UNESCO’s list of intangible cultural heritage.

‘A FORM OF MEDITATION’

Priest Dipak Bajracharya — a member of Ujay’s caste but of no relation to the painter — said that in earlier times paubha artists would stay “pure” to ensure the sanctity of the images they produced.

“The process itself is considered a form of meditation,” he said.

While the traditional religious value remains, paubha paintings are now commonly seen as decorative hangings in museums or the homes of collectors.

A growing international appreciation for the craft has proven lucrative for artists, with interested buyers in China, Japan and Western countries.

“Paubha paintings have now become a business, but their aim is not commercial — they are actually objects of respect and worship,” the priest said.

Dipak returned to Ujay’s home once the latter’s hair had grown back for a final religious ceremony, culminating in a ritual to “breathe life” into the finished painting.

The ceremonial practice invites the Green Tara to reside in the work as a vessel for worship.

“This is not art alone, the faith of Buddhists and Hindus is tied to it,” said Ujay Bajracharya. “If we don’t preserve this art form, the faith will also slowly fade away.”

The primaries for this year’s nine-in-one local elections in November began early in this election cycle, starting last autumn. The local press has been full of tales of intrigue, betrayal, infighting and drama going back to the summer of 2024. This is not widely covered in the English-language press, and the nine-in-one elections are not well understood. The nine-in-one elections refer to the nine levels of local governments that go to the ballot, from the neighborhood and village borough chief level on up to the city mayor and county commissioner level. The main focus is on the 22 special municipality

Words of the Year are not just interesting, they are telling. They are language and attitude barometers that measure what a country sees as important. The trending vocabulary around AI last year reveals a stark divergence in what each society notices and responds to the technological shift. For the Anglosphere it’s fatigue. For China it’s ambition. For Taiwan, it’s pragmatic vigilance. In Taiwan’s annual “representative character” vote, “recall” (罷) took the top spot with over 15,000 votes, followed closely by “scam” (詐). While “recall” speaks to the island’s partisan deadlock — a year defined by legislative recall campaigns and a public exhausted

Hsu Pu-liao (許不了) never lived to see the premiere of his most successful film, The Clown and the Swan (小丑與天鵝, 1985). The movie, which starred Hsu, the “Taiwanese Charlie Chaplin,” outgrossed Jackie Chan’s Heart of Dragon (龍的心), earning NT$9.2 million at the local box office. Forty years after its premiere, the film has become the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute’s (TFAI) 100th restoration. “It is the only one of Hsu’s films whose original negative survived,” says director Kevin Chu (朱延平), one of Taiwan’s most commercially successful

In the 2010s, the Communist Party of China (CCP) began cracking down on Christian churches. Media reports said at the time that various versions of Protestant Christianity were likely the fastest growing religions in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The crackdown was part of a campaign that in turn was part of a larger movement to bring religion under party control. For the Protestant churches, “the government’s aim has been to force all churches into the state-controlled organization,” according to a 2023 article in Christianity Today. That piece was centered on Wang Yi (王怡), the fiery, charismatic pastor of the