A ring shimmers on display at the Consumer Electronics Show, but this is no mere piece of jewelry — it’s packed with sensors capable of detecting body temperature, respiration and much more.

Startups at the annual gadget extravaganza in Las Vegas touted technology-enhanced accessories designed to look fetching on the outside while scrutinizing what is happening on the inside of wearers.

“We want to democratize personal health,” said Amaury Kosman, founder of the French startup that created the Circular Ring.

Photo: Reuters

While that goal was shared by an array of exhibitors, some experts worried a trend of ceaselessly tracking steps, time sitting, heart rate and more could bring risks of stress and addiction.

Circular Ring provides a wearer with a daily “energy score” based on the intensity of their activity, factoring in heart rate, body temperature, blood oxygen levels and other data, according to Kosman.

“At night it continues, we track the phases of sleep, how long it takes you to fall asleep, if you are aligned with your circadian rhythm, etc,” he said of the ring, which will cost less than 300 euros (US$340) when it hits the market later this year.

Photo: Reuters

“And in the morning it vibrates to wake you up at the right time.”

A mobile application synced to the ring is designed to make personalized lifestyle recommendations for improving health based on data gathered, according to the founder.

HIGH DEMAND FOR WEARABLES

Demand for body-tracking “wearables” is strong: CES organizers forecast that more than US$14 billion will be spent this year in a category that includes sports tech, health-monitoring devices, fitness activity trackers, connected exercise equipment and smartwatches.

That figure is more than double what was spent in the category in 2018.

Growth has been driven by smart watches such as those made by powerhouses Apple and Samsung, as well as internet-linked sports gear — which boomed during the pandemic — and personal tracking devices.

Companies are also moving to fill a need for instruments that provide data that can be relied on as part of a pandemic-driven trend of remote health care.

Swiss Biospectal taps into smartphone cameras to measure blood pressure when a finger is placed over a lens.

French Quantiq is developing algorithms that calculate heart rate, respiratory rate and blood pressure from “selfies.”

Meanwhile, Japanese start-up Quantum Operation has designed a prototype bracelet that continuously measures the level of glucose in the blood. Diabetic patients would be spared needle jabs for frequent blood sugar tests.

Body-minding wearables can provide valuable health data, but some fear a “quantified self” trend is blurring the line between well-being and stressful obsession.

GROWING DEPENDENT?

South Korean firm Olive Healthcare displayed a “Bello” infrared scanner that analyzes stomach fat and suggests how to lose it, along with a “Fitto” device that assesses muscle mass and ways to increase it.

Society needs to determine whether these kinds of tools solve problems or “give rise to new dependencies,” contended German political scientist Nils-Eyk Zimmermann.

A danger is that the “digital self” generated by such technology does not match reality, reasoned Zimmermann, who blogs on the topic.

He also saw danger in “game” features, such as rewards and peer competition that put pressure on users that may not be healthy.

Withings’s US sales director Paul Buckley was confident people can handle health data made available from devices such as the Body Scan smart scale unveiled at CES by the French company.

“I don’t think it’s too much,” Buckley said as he showed off the scale capable of performing electrocardiograms and analyzing body composition.

“You’re able to be more informed about what is going on in your body.”

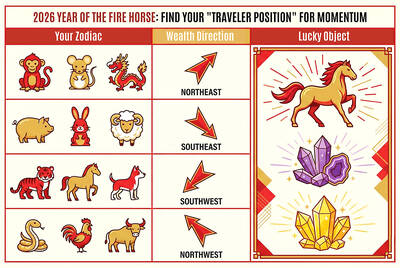

The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists moving the Doomsday Clock to 85 seconds before midnight last month symbolized the closest humanity has ever been to global catastrophe In this context, the legislature remains gridlocked over the general budget, mirroring tensions simmering across the globe. According to local soothsayers, this “extreme speed and violent conflict” is no coincidence as the Year of the Horse is the year of bingwu (丙午), the rare “Fire Horse Year” (火馬年) that occurs once every 60 years, a configuration carrying an energy that shapes everything from personal fortunes to international crises. “For some people, it can be a

Feb. 16 to Feb. 22 Pai Ko’s (白克) film career appeared poised to reach new heights in 1962 with the completion of the highly-anticipated, star-studded Romance of Longshan Temple (龍山寺之戀). Despite being mainly in Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), the film promoted harmony between those born in China and Taiwan, aligning with the official cultural policy at the time. However, he soon disappeared. Colleagues found out he was arrested and accused of colluding with communists. It was not his first run-in with the ruling Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). As a university student in China, he joined the anti-Japanese Anti-Imperialism League and