It’s a saccharine sweet story about a young deer who finds love and friendship in a forest. But the original tale of Bambi, adapted by Disney in 1942, has much darker beginnings as an existential novel about persecution and antisemitism in 1920s Austria.

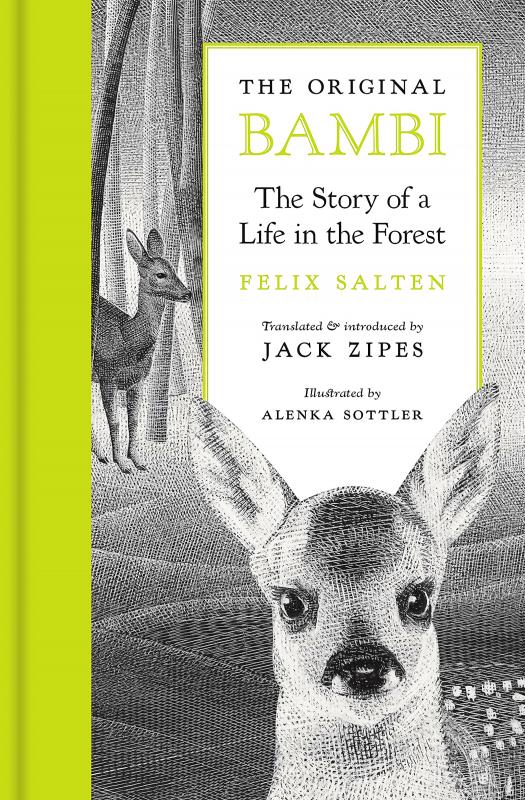

Now, a new translation seeks to reassert the rightful place of Felix Salten’s 1923 masterpiece in adult literature and shine a light on how Salten was trying to warn the world that Jews would be terrorized, dehumanized and murdered in the years to come.

Far from being a children’s story, Bambi was actually a parable about the inhumane treatment and dangerous precariousness of Jews and other minorities in what was then an increasingly fascist world, the new translation will show.

Photo courtesy of Princeton University Press

In 1935, the book was banned by the Nazis, who saw it as a political allegory on the treatment of Jews in Europe and burned it as Jewish propaganda.

“The darker side of Bambi has always been there,” said Jack Zipes, professor emeritus of German and comparative literature at the University of Minnesota and translator of the forthcoming book. “But what happens to Bambi at the end of the novel has been concealed, to a certain extent, by the Disney corporation taking over the book and making it into a pathetic, almost stupid film about a prince and a bourgeois family.”

COMPLETELY DIFFERENT STORY

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Salten’s novel, Bambi, a Life in the Woods, is completely different, Zipes said. “It is a book about survival in your own home.” From the moment he is born, Bambi is under constant threat from hunters who invade the forest and attack indiscriminately. “They kill whatever animal they want.”

It soon becomes apparent that the forest animals are living out their lives in fear and that puts the reader constantly on edge: “All the animals have been persecuted. And I think what shakes the reader is that there are also some animals who are traitors, who help the hunters kill.”

After Bambi’s mother is murdered, so is his beloved cousin Gobo, who had been led to believe he was special and the hunters would be “kind” to him. Bambi is shot too, but survives thanks to the old prince, a majestic stag who treats him like a son (and may well be his father). But then, sadly, the old prince also dies, leaving Bambi utterly bereft.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“Bambi does not survive well, at the end. He is alone, totally alone … It is a tragic story about the loneliness and solitude of Jews and other minority groups.”

There is a sense at the end that Bambi and all the other wild animals in the forest are merely “born to be killed.” They know they will be hunted — and they know they will die. “The major theme throughout is: you don’t have a choice.”

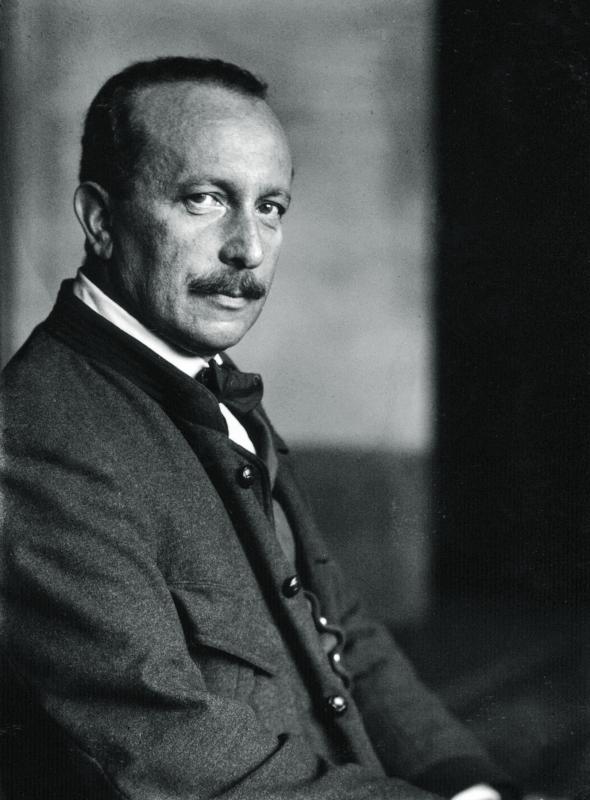

Salten, who had changed his name from Siegmund Salzmann during his teens to “unmark” himself as a Jew in Austrian society, earned his main income as a journalist in Vienna. Zipes thinks he could see the direction in which the political winds were blowing.

“I think he foresaw the Holocaust. He had suffered greatly as a young boy from antisemitism and at that time, in Austria and Germany, Jews were blamed for the loss of the first world war. This novel is an appeal to say: no, this shouldn’t happen.”

At one point in the novel, two leaves on a tree discuss why they must fall to the ground and wonder what will happen to them when they do.

“These leaves talk very seriously about really dark questions humans have: we don’t know what is going to happen to us when we die. We don’t know why we must die.”

‘THESE ARE HUMAN BEINGS’

By writing a story about animals and wildlife, Salten could get past the negative preconceptions and prejudices many of his readers held about Jews and other minorities: “It enabled him to talk about the persecution of the Jews as freely as he wanted to.”

Without being didactic, he could encourage the reader to feel more empathy towards oppressed groups — and Bambi could openly question the cruelty of their oppressors.

“Many other writers, like George Orwell, chose animals too because you’re freer to tackle problems that might make your readers bristle. And you don’t want them to bristle, you want them to say, at the end: this is a tragedy.”

Importantly, the new translation, which will be published on Jan. 18 by Princeton University Press, attempts to convey in English for the first time the way that certain characters in Salten’s novel have a Viennese “flair” when they talk in German.

“The animals have wonderful ways of talking, which makes you feel as though you are in a Viennese cafe. And you immediately recognize that they’re not talking how animals talk. These are human beings.”

By contrast, the original English translation, which was published in 1928, toned down Salten’s anthropomorphism and changed its focus so that it was more likely to be understood as a simple conservation story about animals living in a forest. This was the version read by Walt Disney, who loved animal stories.

When Germany annexed Austria in 1938, Salten managed to flee to Switzerland. By then, he had sold the film rights for a mere US$1,000 to an American director, who then sold them on to Disney: Salten himself never earned a penny from the famous animation. Stripped of his Austrian citizenship by the Nazis, he spent his final years “lonely and in despair” in Zurich and died in 1945, like Bambi, with no safe place to call home.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

Lines between cop and criminal get murky in Joe Carnahan’s The Rip, a crime thriller set across one foggy Miami night, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Damon and Affleck, of course, are so closely associated with Boston — most recently they produced the 2024 heist movie The Instigators there — that a detour to South Florida puts them, a little awkwardly, in an entirely different movie landscape. This is Miami Vice territory or Elmore Leonard Land, not Southie or The Town. In The Rip, they play Miami narcotics officers who come upon a cartel stash house that Lt. Dane Dumars (Damon)

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,

Today Taiwanese accept as legitimate government control of many aspects of land use. That legitimacy hides in plain sight the way the system of authoritarian land grabs that favored big firms in the developmentalist era has given way to a government land grab system that favors big developers in the modern democratic era. Articles 142 and 143 of the Republic of China (ROC) Constitution form the basis of that control. They incorporate the thinking of Sun Yat-sen (孫逸仙) in considering the problems of land in China. Article 143 states: “All land within the territory of the Republic of China shall