This summer Taiwan’s art world has been roiled by a dispute over an exhibition by the artist Jun Yang (楊俊) at the Taipei Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA). The handling of the controversy by the various institutions and actors involved has provoked much discussion in Taiwan’s art world. The incident has much wider implications.

Three years ago Yang, who was born in China but grew up in Austria and has been based in Taiwan and Japan for the last decade, started working on a solo-exhibition series that began at the Art Sonje Center in Seoul, then was exhibited at the Kunsthaus Graz in Austria, and finally moved to Taipei.

The exhibition, which in Taipei was entitled “The Artist, His Collaborators, Their Exhibition, and Three Venues,” was to be shown at three spaces simultaneously in Taipei. Yang describes the exhibition as a series of solo exhibitions “that itself challenges the notion of a solo exhibition/institution/role of artist/art’s social role.”

Photo courtesy of Jun yang

Yang and his co-curator Barbara Steiner negotiated with MOCA Taipei to be one part of this triptych exhibition. The other venues were Kuandu Museum of Fine Arts and TKG+ Projects. Yuki Pan (潘小雪), then the director of MOCA, approved the exhibition but then later in 2019 resigned her position.

THE DISPUTE

An internationally known artist, Yang first came to Taiwan in 2006. In 2008 he participated in the Taipei Biennial. His proposal for a contemporary art center at that show struck a chord in the local art community, and led to the establishment of the Taipei Contemporary Art Center (TCAC) as a place where artists could come together outside of government organizations.

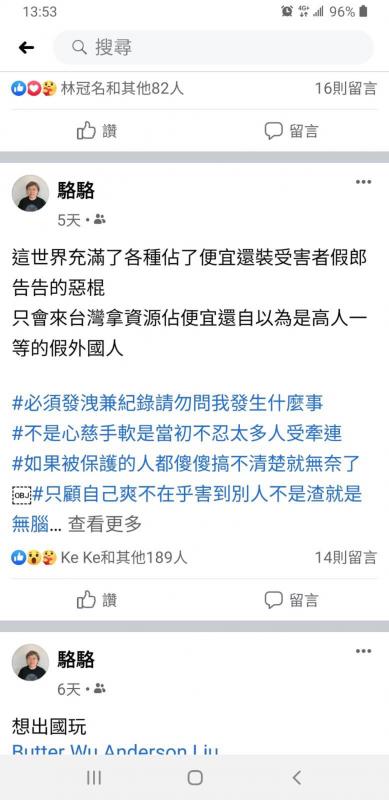

Screengrab from Facebook

The dispute began when the new director of MOCA, Loh Li-chen (駱麗真) canceled the show, allegedly without negotiating with Yang, even though museum officials had assured Yang it would be held as planned. After Yang threatened legal action, the two sides agreed that the show would go on, but only for a month and half, instead of three months. In addition to this Yang observed, because of Lunar New Year in February, the exhibition was effectively further shortened.

The furor in the art world exploded after Yang decided to publicly discuss a xenophobic post Loh posted on Facebook in December during the preparations for the exhibitions: “The world is full of villains who pretend to be victims but really just want to take advantage of you. Fake foreigners who think they’re superior come to Taiwan and take all the resources.” Outrageously, the post was hashtagged “People who only care about themselves, and not about hurting others, are either brainless or scumbags.” Yang also said that he had been bullied by online trolls during the dispute.

MOCA said in a July 31 statement that during the transition to the new director, Yang’s project was lost in the shuffle and Loh had not been properly informed of the exhibition. She thus went on to focus on the upcoming celebrations for MOCA’s 20th anniversary, which had to be shortened because of Yang’s show, the museum said. A proper contract had not been signed, it explained, and the show had not been listed in the museum’s exhibition plan.

MUSEUM RESPONSE?

At first the museum did not comment on the xenophobic post by its director, but later added in an art magazine interview that the director felt sorry, but the Facebook post had named no one.

Officials have since retreated into silence, clearly hoping the incident will just disappear. As Yang observed to this writer, there’s a strange contrast between a public museum director posting such words, and city cultural officialdom hiding in silence.

Many major art museums in the US are headed by independent directors overseen by a board of directors, and are funded by philanthropy. By contrast, in Taiwan, museum directors are directly inside the government bureaucracy and their funding comes largely from the government.

Hence, when trouble hits, they turtle up as bureaucrats will, and prevent the issue from reaching their superiors. When the superiors are contacted, they push the issue back down on their subordinates. What really counts for such people is not what outsiders are doing, but what happens inside the bureaucracy. The outside world is treated as a source of validation for what the bureaucracy is doing, or else it is shrugged off, or punished, if possible.

The well-known writer and scholar Roan Ching-yueh (阮慶岳) noted in a Facebook post discussing the incident and the reactions of the various Taipei cultural organizations involved with MOCA that: “All of them chose the ‘don’t listen, don’t answer, ignore’ response mode that Taiwan’s official style is best at.” Roan also noted that the government issues awards and subsidies to local artists, making it difficult for them to speak up about art without biting the hand that feeds them.

This dispute, widely discussed in the art world, is another example of a long-running problem with interactions between Taiwan’s bureaucracy and foreigners.

As David Frazier, founder of Urban Nomad Film Fest and one of the founders of TCAC, who has interacted with local cultural officialdom for the better part of two decades, put it: “If they can find something overseas and just buy it, and then package it themselves, and the foreigner can come and just wave, they like that model. But when the foreigner tries to take some agency…”

‘TEACHABLE MOMENT’

A Canadian who runs music events in Canada and Sweden and is now in Taiwan pointed out on Facebook in a comment under Frazier’s post that if he had made a similarly xenophobic comment like that in either of those countries, he would have been booted by his funding bodies immediately.

Yang himself sees the incident as a teachable moment. “This is again not a personal vendetta — there is not much to gain for me personally — I will be a persona non grata to a lot of Taipei people no matter what will happen because they will never let this go, but I seriously hope this whole thing can push some discussion.”

He also observed that incidents like this highlight an aspect of Taiwan’s internationalization that is often neglected: the discussion of Taiwan’s place in the world focuses too much on sovereignty and formal recognition.

“Here lies a chance that an international acceptance could take place [this year] beyond the idea of a classical notion of nation,” he told me, “but based on cities, experts (Gold Card program), museum collaborations (like this one), etc.”

It is ironic that Taiwan seeks to raise its international profile, and it has — with unfavorable coverage in the international art press.

This exhibition represented a rare opportunity to work across the aisle on a collaboration with two other venues in Taipei and to work on an international project with spaces in Austria and South Korea. Sadly, this case highlights how bureaucrats in Taiwan, especially at the local level, do not see themselves as governing officials of a country whose continued independent existence depends on strong outside support which they should be eagerly courting, but instead, too often appear to imagine that they are administrators of a grand imperial project that others must kow-tow to.

This insularity is a threat to the island’s future. It must go.

Notes from Central Taiwan is a column written by long-term resident Michael Turton, who provides incisive commentary informed by three decades of living in and writing about his adoptive country. The views expressed here are his own.

Jacques Poissant’s suffering stopped the day he asked his daughter if it would be “cowardly to ask to be helped to die.” The retired Canadian insurance adviser was 93, and “was wasting away” after a long battle with prostate cancer. “He no longer had any zest for life,” Josee Poissant said. Last year her mother made the same choice at 96 when she realized she would not be getting out of hospital. She died surrounded by her children and their partners listening to the music she loved. “She was at peace. She sang until she went to sleep.” Josee Poissant remembers it as a beautiful

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades

Lori Sepich smoked for years and sometimes skipped taking her blood pressure medicine. But she never thought she’d have a heart attack. The possibility “just wasn’t registering with me,” said the 64-year-old from Memphis, Tennessee, who suffered two of them 13 years apart. She’s far from alone. More than 60 million women in the US live with cardiovascular disease, which includes heart disease as well as stroke, heart failure and atrial fibrillation. And despite the myth that heart attacks mostly strike men, women are vulnerable too. Overall in the US, 1 in 5 women dies of cardiovascular disease each year, 37,000 of them

Politically charged thriller One Battle After Another won six prizes, including best picture, at the British Academy Film Awards on Sunday, building momentum ahead of Hollywood’s Academy Awards next month. Blues-steeped vampire epic Sinners and gothic horror story Frankenstein won three awards each, while Shakespearean family tragedy Hamnet won two including best British film. One Battle After Another, Paul Thomas Anderson’s explosive film about a group of revolutionaries in chaotic conflict with the state, won awards for directing, adapted screenplay, cinematography and editing, as well as for Sean Penn’s supporting performance as an obsessed military officer. “This is very overwhelming and wonderful,” Anderson