Long before American sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos made history with their Black Power salute at the 1968 Olympics, another poignant image of silent protest was etched into the conscience of Koreans — and largely forgotten everywhere else.

At the Berlin Olympics in 1936, Korean Sohn Kee-chung stood with his head hung, hiding the rising-sun flag on his chest with a laurel plant as Japan’s national anthem filled the stadium to honor his marathon victory. The moment filled him with “unbearable humiliation,” he recounted in his autobiography, and marked the beginning of an anguished chapter in his life.

Worried that his triumph would spark an insurgence among ethnic Koreans, Japan — which ruled Korea from 1910 to 1945 — forbade Sohn from competitive running, kept him under tight surveillance, and even used his celebrated status to recruit young Koreans for its war effort. Sohn called the recruiting the “greatest regret” of his life.

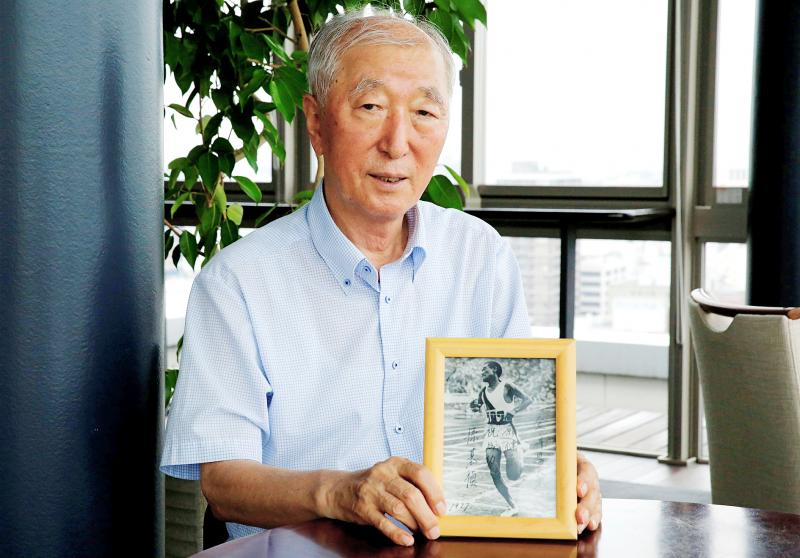

Photo: Kyodo via Reuters

Still, Sohn harbored no resentment toward his former oppressors in later years and dedicated his life to promoting “Olympism” — or peace through sports — particularly between Japan and Korea, his son, Chung-in, said in a recent interview.

“All he wished for was for both sides to recognize what happened in the past so we don’t repeat it, and instead look forward,” he said.

‘UNCOMFORTABLE TOPIC’

Photo: Kyodo via Reuters

With bilateral relations at a nadir today, mostly over wartime atrocities, Sohn’s message remains relevant, said Zenichi Terashima, professor emeritus at Tokyo’s Meiji University, who published the runner’s biography two years ago.

For all of Sohn’s efforts at reconciliation, Japan has had an awkward relationship with him and his legacy, Terashima said, speaking alongside his son.

Sohn is a national hero in South Korea, but few in Japan have heard of him, even though his medal remains the only Olympic gold for the men’s marathon in Japan.

Photo: Reuters

Only an eagle-eyed visitor to the new Olympic museum in Tokyo will notice both mentions of Sohn: one among a display of Japanese gold medallists and another in a tiny sign accompanying the Olympic torch used in the Seoul Games in 1988 describing him as the final torch relay runner.

“He’s an uncomfortable topic in Japan,” said Terashima, who said he felt compelled to publish Sohn’s life story amid what he perceived as a resurgence of historical revisionism among Japan’s conservative elite.

OLIVE BRANCH

Sohn scrupulously avoided politics and extended an olive branch wherever he saw a chance.

When Japanese runner Shigeki Tanaka won the Boston marathon in 1951, Sohn sent him a congratulatory message, calling his win “a win for Asia,” his son said. He signed off using the Japanese transliteration of his name — Son Kitei — a profound gesture from a man who insisted on signing autographs in Korean even in 1936.

It should have been a bitter moment. The previous year, Sohn had coached the Korean team that swept first, second and third places at the marquee race, only to be denied entry in 1951 as the Korean War raged.

At Seoul 1988, Sohn had secretly planned to gift a replica of the ancient Corinthian helmet given to him as Berlin’s marathon winner to a Japanese runner if they won a medal, his son recalled.

Sohn was ecstatic about Japan and South Korea’s co-hosting of the 2002 FIFA World Cup, instructing his son to help make it a success so “the past could be left in the past for a fresh start,” Chung-in said. Sohn died a few months after the event.

The thaw in bilateral ties proved short-lived, but “my father died a happy man,” Chung-in said.

The current diplomatic chill has spilled over into the Olympics in the form of a territorial dispute over the labelling of a set of islands — both at the Pyeongchang Olympics in 2018 and this year.

But Terashima says the “Olympism” that Sohn advanced thrives in the activism of Naomi Osaka today and the borderless bonds shared by speedskaters Nao Kodaira and Lee Sang-hwa, whose emotional embrace after their race at Pyeongchang, draped in the Japanese and Korean flags, moved many on both sides of the sea.

“My father liked to say that in war, whether you win or lose, if a bullet hits you, you die,” Chung-in said. “But that in sports, even if you lose, you can still be friends.”

Oct. 27 to Nov. 2 Over a breakfast of soymilk and fried dough costing less than NT$400, seven officials and engineers agreed on a NT$400 million plan — unaware that it would mark the beginning of Taiwan’s semiconductor empire. It was a cold February morning in 1974. Gathered at the unassuming shop were Economics minister Sun Yun-hsuan (孫運璿), director-general of Transportation and Communications Kao Yu-shu (高玉樹), Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) president Wang Chao-chen (王兆振), Telecommunications Laboratories director Kang Pao-huang (康寶煌), Executive Yuan secretary-general Fei Hua (費驊), director-general of Telecommunications Fang Hsien-chi (方賢齊) and Radio Corporation of America (RCA) Laboratories director Pan

The consensus on the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) chair race is that Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) ran a populist, ideological back-to-basics campaign and soundly defeated former Taipei mayor Hau Lung-bin (郝龍斌), the candidate backed by the big institutional players. Cheng tapped into a wave of popular enthusiasm within the KMT, while the institutional players’ get-out-the-vote abilities fell flat, suggesting their power has weakened significantly. Yet, a closer look at the race paints a more complicated picture, raising questions about some analysts’ conclusions, including my own. TURNOUT Here is a surprising statistic: Turnout was 130,678, or 39.46 percent of the 331,145 eligible party

The classic warmth of a good old-fashioned izakaya beckons you in, all cozy nooks and dark wood finishes, as tables order a third round and waiters sling tapas-sized bites and assorted — sometimes unidentifiable — skewered meats. But there’s a romantic hush about this Ximending (西門町) hotspot, with cocktails savored, plating elegant and never rushed and daters and diners lit by candlelight and chandelier. Each chair is mismatched and the assorted tables appear to be the fanciest picks from a nearby flea market. A naked sewing mannequin stands in a dimly lit corner, adorned with antique mirrors and draped foliage

The election of Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) as chair of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) marked a triumphant return of pride in the “Chinese” in the party name. Cheng wants Taiwanese to be proud to call themselves Chinese again. The unambiguous winner was a return to the KMT ideology that formed in the early 2000s under then chairman Lien Chan (連戰) and president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) put into practice as far as he could, until ultimately thwarted by hundreds of thousands of protestors thronging the streets in what became known as the Sunflower movement in 2014. Cheng is an unambiguous Chinese ethnonationalist,