An old saw blade has sat on architect Sun Chi-jung’s (孫啟榕) office desk for over a decade.

He found it lodged in a cypress column of a Japanese-era dormitory in Taipei he was tasked to preserve, during the height of a struggle between preservationists and developers who were trying to destroy these houses that sat on prime real estate.

“This is to remind myself to never, never let something like this happen again,” Sun says emphatically.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

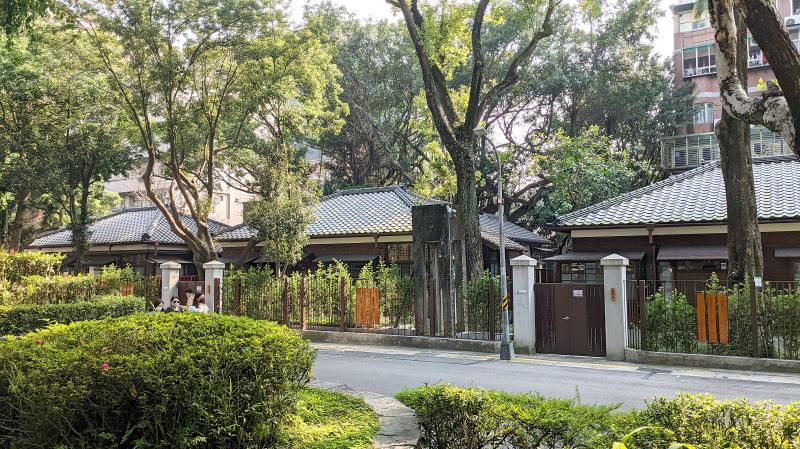

Today, Sun proudly shows visitors what has become of his initial efforts to preserve what is commonly known as the Qidong Street (齊東街) Japanese dorms, one of the best-preserved clusters of such buildings in Taipei. The latest to open to the public is the Taiwan Literature Base (台灣文學基地), launched in December last year.

Sun is responsible for two of the seven buildings in the Literature Base and the additional two behind it that make up the Taipei Qin Hall (台北琴道館) and the Taipei Calligraphy and Painting Garden (台北書畫院). His passion for saving the past is evident as he takes me on an hour-long tour of the area.

Sun repeatedly mentions how grateful he is to be able to participate in this project, and rattles off a list of names that made it possible. But one woman receives particular attention: Chu-Chen Pao-kuei (褚陳寶貴), the housewife-turned-activist and community organizer who spearheaded the charge to save these buildings before Sun came on board.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

“If not for Chu-Chen Pao-kuei, this place wouldn’t be here,” Sun says.

CALL TO ACTION

I meet Chu-Chen at the Literature Base, where she speaks at length about the area’s history, civic engagement, community building as well as historic and environmental preservation.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

“I didn’t know any of this stuff before,” she says. “I was just a very ordinary housewife. Now that I look back, I have no idea where my determination came from.”

These days, she’s no longer as involved as she is busy taking care of her husband who suffered a stroke, but she’s glad that young people are now helping run the Literature Base.

“The most important thing is to utilize the space meaningfully,” she says. “We’ve managed to preserve this beautiful place, but we need to attract visitors for it to be sustainable. That’s the task of the younger generation, and I fully support whatever they do.”

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Qidong Street has been active since the Qing Dynasty as a major throughway, and when the Japanese arrived, they built many traditional-style dorms in the neighborhood to house officials and civil servants. Surviving structures can be found scattered through the area, I detail many of them in a walking tour article published on Feb. 3.

After World War II, the Qidong Street dorms, mostly built between 1920 and 1940, housed Bank of Taiwan staff and other government officials. As Taipei’s development pushed eastward, the land here became immensely valuable real estate, and the bank sold it to developers around 2000.

Chu-Chen says when she heard that the whole block could be razed, the only thought on her mind was to “save the old trees.”

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

“I just wanted to continue living in a place where I would be woken up by the sounds of birds and insects in the morning,” she says. Her appreciation for the dorms came soon after.

Chu-Chen rallied her neighbors and founded the Qidong Street Cultural and History Office (齊東街文史工作室) to protect the dorms, and enrolled in community planning classes to learn how to carry out the out the fight.

The first demolition crew appeared in December 2002, but the residents banded together and managed to stop them before they got too far.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

MIDNIGHT DEMOLITION

The following spring, the Taipei City Department of Cultural Affairs agreed to protect the cluster of dorms, but even that didn’t stop the developers. The night before the buildings were to officially obtain their historic status, workers arrived in the middle of the night and completely flattened one of them.

As the vandalism continued, a furious Liao Hsien-hao (廖咸浩), who had just assumed his post as the city’s head of cultural affairs, personally arrived to put up notices and installed a metal security booth on the street.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Sun hopes that the city preserves the booth within the Literature Base. Even though it has no historic value, he says it is a testament to the struggle that happened here.

“It witnessed our determination to protect our cultural heritage,” he says.

Meanwhile, Chu-Chen launched a series of neighborhood classes for both adults and children to boost community cohesion. She needed strength in numbers to resist the threats of the developers, and she also wanted more locals to understand how precious these trees and dorms were. Whatever the subject was, whether it be yoga, harmonica, art or personal development, it would always include material about the neighborhood.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Many of these classes continue to this day. They also collected and recorded the history of this area and held exhibitions in the restored dorms. Chu-Chen says she has lost count of how many historic tours she’s led. Their efforts are on display at the Literature Base’s main exhibition hall.

Sun says his motivation is simple: he was fortunate enough to receive a good education and become an architect, and he wanted to give back by speaking for the voiceless.

“These include the trees, the buildings and the neighborhood mothers who love this place but don’t know how to save it,” he says.

In 2013, the first two buildings that he restored opened to the public. The following year, the Literature Base’s precursor, the Qidong Poetry Salon (齊東詩舍) also opened. Sun lost the bid to fix the remaining buildings to Hsu Po-yuan (許伯元), but speaks glowingly of Hsu’s work.

He gets emotional when he talks about other buildings that have been lost.

“I’m already 56, and there’s just so much more I can do,” he says. “But what I can’t do, my students can do. If they can’t, their students can try. We need to preserve what we can for future generations, as our cultural heritage belongs to them. How can we face the next generation if we destroy everything now and build high rises in their place?”

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

Every now and then, even hardcore hikers like to sleep in, leave the heavy gear at home and just enjoy a relaxed half-day stroll in the mountains: no cold, no steep uphills, no pressure to walk a certain distance in a day. In the winter, the mild climate and lower elevations of the forests in Taiwan’s far south offer a number of easy escapes like this. A prime example is the river above Mudan Reservoir (牡丹水庫): with shallow water, gentle current, abundant wildlife and a complete lack of tourists, this walk is accessible to nearly everyone but still feels quite remote.

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

It’s a bold filmmaking choice to have a countdown clock on the screen for most of your movie. In the best-case scenario for a movie like Mercy, in which a Los Angeles detective has to prove his innocence to an artificial intelligence judge within said time limit, it heightens the tension. Who hasn’t gotten sweaty palms in, say, a Mission: Impossible movie when the bomb is ticking down and Tom Cruise still hasn’t cleared the building? Why not just extend it for the duration? Perhaps in a better movie it might have worked. Sadly in Mercy, it’s an ever-present reminder of just