Feb. 8 to Feb. 14

Lin Chih-chu (林之助) spent over three decades trying to convince critics that his art form, commonly known today as Eastern gouache, was rooted in Chinese art, not Japanese.

Born in 1917, Lin did learn his craft in Japan and made it into the prestigious Imperial Art Exhibition at the age of 24. But due to the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) anti-Japanese sentiment after they took over Taiwan following Japan’s defeat in World War II, Lin was criticized for promoting the art of the former colonizers. Although Eastern gouache was still allowed in the Taiwan Provincial Art Exhibition, Lin was unable to officially teach it.

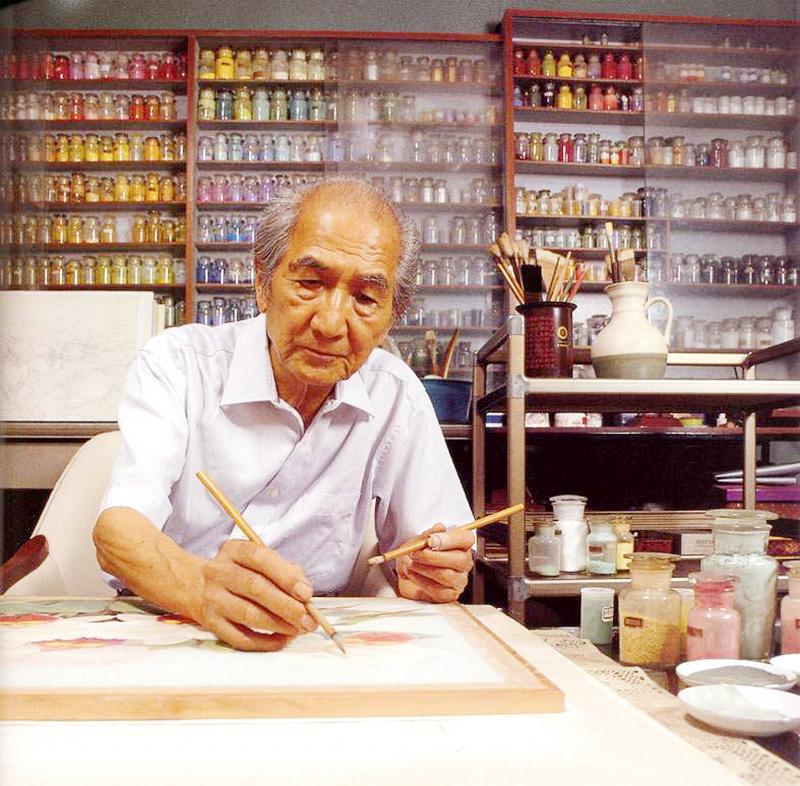

Photo: Taipei Times file photo

As public displeasure toward Japan grew after it broke relations with Taiwan in 1972, the provincial exhibition’s organizers banned Eastern gouache the following year.

“The materials, ink, paper and both mineral and soil pigment in Japanese painting are virtually identical to that of Chinese,” Lin argued. “The brush and coloring techniques are also rooted in Chinese art. Some people say the Tang Dynasty’s female figure paintings represent those of Japanese, but actually, it’s the Japanese female figure paintings that resemble those of the Tang Dynasty’s … Why do we have to reject this art form and let it disappear?”

Lin refused to give up. Finally in 1982, the government allowed his beloved art form back into the provincial exhibition under its own category with a new name that he coined in 1977: “glue color painting” (膠彩畫). Lin tirelessly promoted it until his death on Feb. 13, 2008.

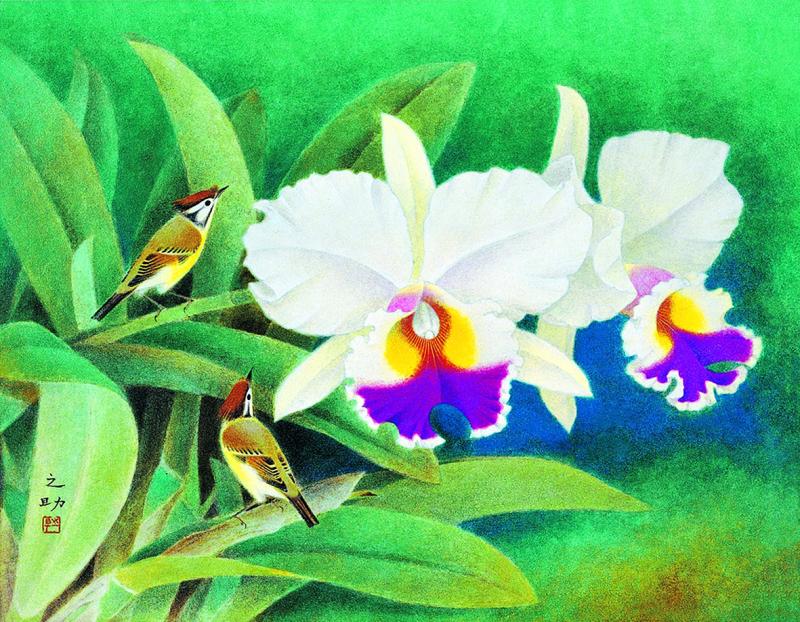

Photo courtesy of National Museum of History

EARLY SUCCESS

Lin’s family from Taichung had the wealth to send him to study in Tokyo at the age of 11. His father hoped that he would become a doctor, but Lin spent most of his time painting and playing sports.

According to art historian Liao Chin-yuan (廖瑾瑗), Lin announced that he would pursue art after finishing secondary school and, unlike many parents of that time, his father supported his decision.

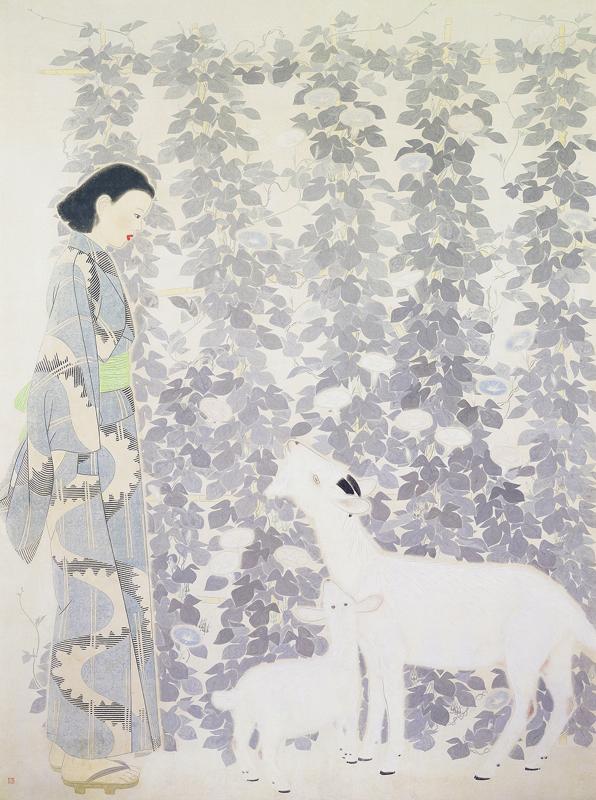

Photo courtesy of National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts

After finishing art school, Lin studied under renowned painter Kodama Kibou, whose 70 to 80 students competed against each other fiercely. In 1939, Lin sold his first work, Rice Shop (米店), to a well-known local restaurant. He tried to look for the shop many years later, but it had shut down and his painting was lost.

The following year was an eventful one for Lin. The day before his wedding to Wang Tsai-chu (王彩珠), whom he was introduced to on a trip back home, he learned that his work Coolness of the Morning (朝涼) was accepted into the Imperial Art Exhibition. That year’s exhibition was a special one, as it marked the 2,600th anniversary of Japanese imperial rule. When Lin arrived at the venue, he was shocked to learn that his painting was exhibited prominently in the first hall.

News of his success soon reached home. Under the invitation of prominent Taiwanese artists, Lin submitted a piece to the Taiyang Art Exhibition (台陽美術展) in 1941. World War II was raging, and Lin mulled heading back to Taiwan. Although Kodama tried hard to persuade him to stay, Lin set sail in September to discuss the matter with his father. While on the ship, news broke that Japan was ready to go to war with the Allies if they didn’t comply with the empire’s demands within a month. Lin sensed that his decision had already been made for him.

RESISTING OPPRESSION

Lin flourished in the Taiwan art scene, claiming top honors in the Governor General’s Office Art Exhibition three years in a row. He taught watercolor and sketching at Taichung Normal University (today’s National Taichung University of Education) after the war, and although they weren’t his preferred media, he was eager to cultivate the next generation of Taiwanese artists. He did demonstrate some basics of Eastern gouache, and a few enthusiastic students continued to learn from him after school hours.

Those who knew Lin say that he never steered any student toward the medium; he only taught those who approached him. But he soon gained a sizable group of disciples who submitted Eastern gouache paintings to various major exhibitions and met regularly to discuss and promote the artform.

Pushback against Eastern gouache began in the 1950s, when some began to question why it was included in the “national painting” category for the provincial exhibition when it was something passed down by the former Japanese colonizers. Lin tried to explain that the medium originated in China, but opposing voices only grew louder. In 1960, the organizers divided the national painting category into two — one for traditional brush painting and one for Eastern gouache — in an attempt to settle the dispute.

Lin wasn’t happy, but he accepted the situation — that is until the Eastern gouache was banned in 1973 from the provincial exhibition without any explanation or prior notice. In 1977, he announced that the medium would henceforth be called “glue color painting,” named after the watermedia to avoid any further controversy.

That June, he held the nation’s first glue color painting group exhibition at the Lungmen Gallery (龍門畫廊) and formed the Taiwan Glue Painting Association (台灣膠彩協會) in 1981. The following year, the artform was finally welcomed back to the provincial exhibition, and Lin commemorated the occasion with a massive piece featuring a peacock flaunting its feathers.

In 1985, he taught the first ever university-level Eastern gouache class at Tunghai University. With that, his mission to legitimize his beloved artform was complete.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Jacques Poissant’s suffering stopped the day he asked his daughter if it would be “cowardly to ask to be helped to die.” The retired Canadian insurance adviser was 93, and “was wasting away” after a long battle with prostate cancer. “He no longer had any zest for life,” Josee Poissant said. Last year her mother made the same choice at 96 when she realized she would not be getting out of hospital. She died surrounded by her children and their partners listening to the music she loved. “She was at peace. She sang until she went to sleep.” Josee Poissant remembers it as a beautiful

For many centuries from the medieval to the early modern era, the island port of Hirado on the northwestern tip of Kyushu in Japan was the epicenter of piracy in East Asia. From bases in Hirado the notorious wokou (倭寇) terrorized Korea and China. They raided coastal towns, carrying off people into slavery and looting everything from grain to porcelain to bells in Buddhist temples. Kyushu itself operated a thriving trade with China in sulfur, a necessary ingredient of the gunpowder that powered militaries from Europe to Japan. Over time Hirado developed into a full service stop for pirates. Booty could

Lori Sepich smoked for years and sometimes skipped taking her blood pressure medicine. But she never thought she’d have a heart attack. The possibility “just wasn’t registering with me,” said the 64-year-old from Memphis, Tennessee, who suffered two of them 13 years apart. She’s far from alone. More than 60 million women in the US live with cardiovascular disease, which includes heart disease as well as stroke, heart failure and atrial fibrillation. And despite the myth that heart attacks mostly strike men, women are vulnerable too. Overall in the US, 1 in 5 women dies of cardiovascular disease each year, 37,000 of them

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades