The Batongguan Traversing Trail (八通關越道路) was built during the Japanese era in order to provide a transportation link between the East and West, and a means to control the Aboriginal population in the mountains. Construction began in 1919 and the entire 125-kilometer project was completed just a year and a half later. It was used until 1944, when the financial strain of the war effort forced its abandonment.

THE WESTERN SECTION

Nowadays, 96 kilometers of the original trail remain, taking hikers from Dongpu (東埔) in Nantou County to Yuli (玉里) in Hualien County. The first few kilometers on the west can be crowded with day tourists walking up to see the stunning Yunlong Waterfall (雲龍瀑布), but the crowds thin out rapidly after this point.

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

The trail continues its slow, steady climb into the mountains. Hiking trails in Taiwan are often steep, following ridgelines and peaks, but the slope of the Batongguan is gentle, as it was designed to allow for cart traffic transporting goods. Around 15 kilometers in is one of the major landmarks and intersections on the trail: the Batongguan Meadow.

This was the site of one of the largest police stations on the Batongguan and played host to Japanese hikers of the past making the trek up to Taiwan’s highest mountain on a side trail that begins here. Nowadays, the outline of the site is still obvious, and the concrete entrance pillars are still standing amid the tall grass. Some hikers still use the same side trail today to reach Jade Mountain, the top of Taiwan. In fact, joining up with the Batongguan via Jade Mountain is an excellent alternative to starting in Dongpu.

The trail continues past an old gold mining site, eventually reaching a beautiful mountain pass covered in short Yushan cane bamboo where the trail crosses over the spine of the Central Mountain Range. Ruins of the Japanese police station Dashuiku (大水窟) can be visited, and a modern shelter constructed by Yushan (Jade Mountain) National Park is available here for hikers’ use.

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

THE CHALLENGING EASTERN SECTION

The western portion of the Batongguan is more heavily trafficked, as several of the major 100 Peaks routes make use of it. The eastern section, however, fell rapidly into disrepair after World War II and is still rarely visited. The National Park restored the trail and reopened it in 2005, but this section remains full of narrow sections, cliffs and detours, and as such is not suitable for beginners. However, it is worth exploring as the ruins are more abundant and better preserved on the east side.

The first major attraction here is the Tomas Police Station (托馬斯駐在所). Though no buildings remain, stone walls separating different tiers on the site are very well preserved, and bits of original fencing still stand. Old glass beer and sake bottles from the Japanese era litter the site. There are even ceramic insulators showing where telephone lines used to run, connecting remote mountain police stations with the rest of the island. The site is a testament to the resources the Japanese were willing to invest in controlling and exploiting every remote corner of Taiwan.

Photo courtesy of Ching-Hsien Hsu

Farther along, the trail disappears in a landslide and a river crossing is required in order to pick up the trail on the other side. This is yet another reason careful planning is required for anyone wanting to walk the whole Batongguan. In fact, earlier this year a solo hiker without GPS got lost at this spot and was only rescued after nine days.

More danger awaits a little farther down the path, just after the Yisila (意西拉) suspension bridges. Have your camera ready as you cross the river here: the newer suspension bridge sits adjacent to the original Japanese bridge, which is now only hanging on by a steel thread. Though the bridge deck is rotted away, the Formosan cypress towers still stand, and it is by far the best preserved of the original bridges on the Batongguan.

After crossing the new bridge, put away your camera, and all other valuables, as you prepare to cross what the author deems the most dangerous section of trail he has seen anywhere in Taiwan. Merely inches wide here, the trail sits on a 70-degree cliff face a hundred meters above the river below, with not a handhold in sight. One wrong step here means certain death, so tread carefully.

Photo courtesy of Ching-Hsien Hsu

A BUSTLING VILLAGE DEEP IN THE MOUNTAINS

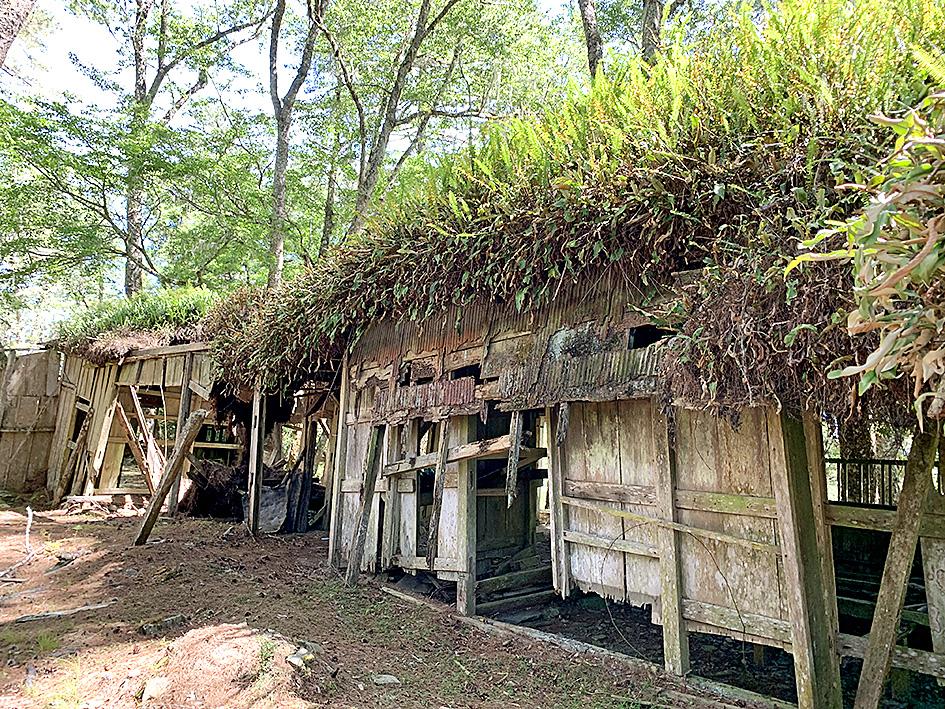

Continuing on, the trail reaches Dafen (大分), where many opt to spend two nights. Besides being a center for Formosan black bear research, there are hot (solar-powered) showers available sporadically in the new hiker’s shelter, and a half-day side trip can be made to the Huabanuo Fort (華巴諾砲台). This fort was the Japanese administration’s way of further extending its tentacles of power into Taiwan’s remote mountains. Unlike all the police stations on the main Batongguan trail, the original wooden structures are still standing here, including one that houses a massive iron cannon.

Dafen itself was once a major settlement, with over a dozen buildings ranging from a clubhouse to a martial arts hall to dormitories. Classes were held here for Bunun youth in the area until the Japanese forced the Aborigines to relocate to lower land in the 1930s. Today, only the concrete ammunition depot still stands, but the multi-tiered layout of the settlement remains relatively clear of vegetation, so it’s possible to walk around and get an appreciation of its size.

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

Though settlements like Dafen did offer services to the local Aboriginal population, it must be remembered that the main purpose of this trail was in fact to exert control over them and allow the Japanese to quickly quell any further rebellion. Reminders of this fact dot the eastern section of the Batongguan in the form of concrete pillars inscribed with Japanese characters commemorating various officials and policemen who were killed by Bunun in protest against Japanese rule, which prompted the construction of the trail itself.

The trail’s condition improves from Dafen eastward as it becomes more heavily trafficked again. This final section is especially picturesque, with the beautifully preserved herringbone-pattern stone walls of Tomiri Police Station (多美麗駐在所) and several towering new suspension bridges. Tourists reappear as one nears civilization again, since the last 14 km of trail are now designated as the Walami Trail (瓦拉米步道), a popular day hike or overnight hike.

The trail suddenly ends in asphalt at the beginning of Provincial Highway 30, which mostly follows the Batongguan route down to Yuli. In the 1970s, this highway was originally slated to cross the island from Yuli all the way to where Provincial Highways 18 and 21 meet near Jade Mountain, passing through Dafen and the Batongguan Meadow along the way. Instead, this part of Taiwan’s wilderness and the old Japanese trail were left intact as part of the planned Yushan National Park. Now, it remains accessible only on foot to those hikers who are prepared to dedicate a week of their lives exploring this historical and natural jewel.

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

Jan. 5 to Jan. 11 Of the more than 3,000km of sugar railway that once criss-crossed central and southern Taiwan, just 16.1km remain in operation today. By the time Dafydd Fell began photographing the network in earnest in 1994, it was already well past its heyday. The system had been significantly cut back, leaving behind abandoned stations, rusting rolling stock and crumbling facilities. This reduction continued during the five years of his documentation, adding urgency to his task. As passenger services had already ceased by then, Fell had to wait for the sugarcane harvest season each year, which typically ran from

It’s a good thing that 2025 is over. Yes, I fully expect we will look back on the year with nostalgia, once we have experienced this year and 2027. Traditionally at New Years much discourse is devoted to discussing what happened the previous year. Let’s have a look at what didn’t happen. Many bad things did not happen. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) did not attack Taiwan. We didn’t have a massive, destructive earthquake or drought. We didn’t have a major human pandemic. No widespread unemployment or other destructive social events. Nothing serious was done about Taiwan’s swelling birth rate catastrophe.

Words of the Year are not just interesting, they are telling. They are language and attitude barometers that measure what a country sees as important. The trending vocabulary around AI last year reveals a stark divergence in what each society notices and responds to the technological shift. For the Anglosphere it’s fatigue. For China it’s ambition. For Taiwan, it’s pragmatic vigilance. In Taiwan’s annual “representative character” vote, “recall” (罷) took the top spot with over 15,000 votes, followed closely by “scam” (詐). While “recall” speaks to the island’s partisan deadlock — a year defined by legislative recall campaigns and a public exhausted

In the 2010s, the Communist Party of China (CCP) began cracking down on Christian churches. Media reports said at the time that various versions of Protestant Christianity were likely the fastest growing religions in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The crackdown was part of a campaign that in turn was part of a larger movement to bring religion under party control. For the Protestant churches, “the government’s aim has been to force all churches into the state-controlled organization,” according to a 2023 article in Christianity Today. That piece was centered on Wang Yi (王怡), the fiery, charismatic pastor of the