Red brick has been a key feature of Taiwan’s built environment since the 1895-1945 period of Japanese rule. The elegance of several colonial-era landmarks — including the Red House (西門紅樓) in Taipei’s Ximending and Kaohsiung’s Wude Hall (高雄武德殿), also known as Takao Butokuden — derives in large part from the use of red bricks in conjunction with concrete.

Possibly the oldest red-brick building standing in Taiwan is Oxford College (牛津學堂). Commissioned by George Mackay, a Presbyterian missionary from Canada, it was completed in 1882. It’s now a museum on the campus of Aletheia University (真理大學), in a neighborhood dotted with century-old red-brick structures in New Taipei City’s Tamsui District (淡水).

During the Japanese era and for some years afterward, few people could afford to build a house entirely of bricks. Even now, in the countryside it isn’t difficult to find single-storey abodes where the external walls are brick from ground level to waist height only. The upper section is sometimes wood, but more often wattle (a woven lattice of bamboo slats) and daub (a mixture of mud, rice husks, and pig dung).

Photo: Steven Crook

By the time central Taiwan was ravaged by catastrophic floods in August 1959, the country had become somewhat more prosperous. Rebuilding efforts began as soon as the waters receded, but were stymied by a shortage of bricks.

Even though the authorities urged brickworks to step up production, huge demand caused brick prices to rise. Seeing an opportunity, the founders of what’s now called Jinshuncheng Bagua Kiln (金順成八卦窯) in Changhua County’s Huatan Township (花壇) established a new brickworks on a plot of land 1.5km east of Huatan Railway Station.

The Huatan area has the right kind of clay for making bricks, and Jinshuncheng Bagua Kiln was neither the first nor the last brickworks to operate in the township. The “bagua” in its name comes from its shape, which is said to resemble the common octagonal depiction of the Eight Trigrams (symbols used in Taoist cosmology).

Photo: Steven Crook

NOTABLE LANDMARK

As far as industrial-heritage enthusiasts are concerned, this landmark is notable because it’s the last remaining Hoffmann-type kiln in central Taiwan.

This design, patented by Friedrich Hoffmann of Germany in 1858, makes it possible to fire bricks nonstop. For this reason, these brickworks are sometimes called “Hoffmann continuous kilns.”

Photo: Steven Crook

Previously, an entrepreneur operating a traditional kiln had to waste several days loading it with unfired bricks before the firing process could begin. Loading can never be rushed, as ware has to be stacked in a way that makes efficient use of the available space, yet not so tightly that hot air can’t circulate.

In a Hoffmann-type brickworks, a fire is kept burning in the central oblong bunker, fuel being added through hatches on the roof. Jinshuncheng Bagua Kiln ran mainly on timber from the forests in Taiwan’s interior. Wood scraps and rice chaff were secondary fuels.

Heat was directed to whichever part of the tunnel-like wraparound chamber needed it. Partitions weren’t necessary: When full heat was being applied to one batch of bricks (typically 1,700 to 1,800 for this kiln), heat escaping to one side ensured that a just-fired batch didn’t cool too quickly, while hot air drifting to the other side slowly preheated the next batch.

Photo: Steven Crook

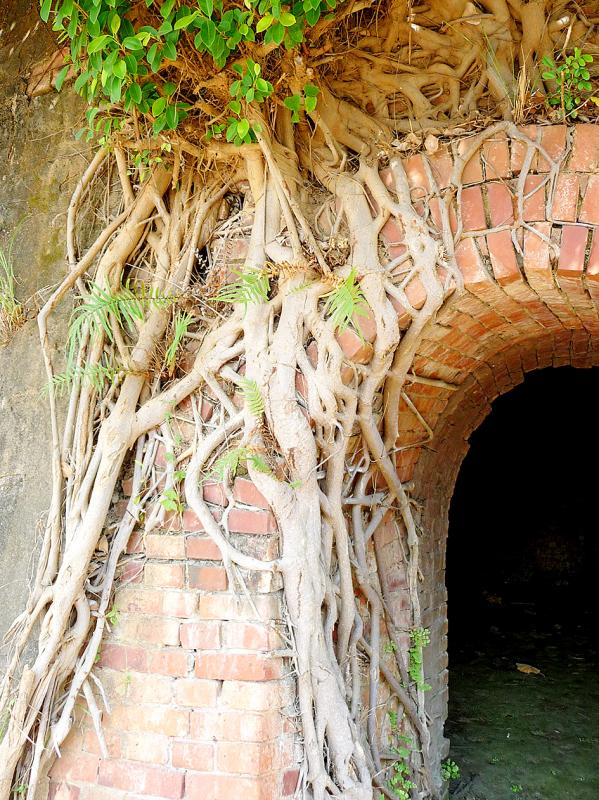

Bricks were loaded and removed through 22 arched apertures on the sides. Most are intact, and through them explorers can access the kiln’s interior.

The interplay of light and shadow inside attracts photography enthusiasts. Do tread carefully: The floor is littered with brick fragments, there’s some trash, and it can get muddy after rain.

The top of the smokestack (which bears the date “1961”) broke off at some point in the past, and steel buttresses hold up sagging sections of roof. Overall, however, the kiln looks as if it’ll survive for a good while yet.

Despite reinforced concrete now being the preferred construction material, considerable numbers of bricks are still made in Taiwan. In the last decade, annual production averaged more than 700 million. The great majority were fired in electric kilns.

As the government took steps to protect the country’s forests, procuring sufficient wood to fuel Jinshuncheng Bagua Kiln became more difficult. The kiln fired its last bricks sometime in the 1980s — no one seems to know the precise date.

The kiln has been listed as heritage site by Changhua County Government since 2010, yet little has been done to present it as a tourist attraction. The only information board isn’t very legible, let alone informative, even if you can read Chinese. There are no set opening hours, and when I visited it looked as if the surrounding weeds hadn’t been trimmed for a long time.

If you’re seeking a more touristy experience in Huatan, you can also visit Shunda Brick Kiln (順達窯業). Originally a conventional manufacturer of bricks and tiles established in 1965, this business converted itself into a teaching/DIY-art activity facility after the demand for bricks slumped. To find out more, or to contact them before going, visit: www.facebook.com/sdyourbrick/.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.