Barbara Brix admired her father, a doctor who passed on his love of history and literature. Until she learned years after his passing that he had been part of a Nazi death squad.

“I didn’t meet my father until I was six years old. When he came back from the war, he had lost both his legs,” said Brix, a 79-year-old German pensioner.

“He read Tolstoy, Dickens to me... He was kind of my spiritual mentor,” said the retired history teacher in her small apartment in an alternative district of Hamburg. “My father didn’t talk about it and I didn’t ask any questions, not even this simple question: ‘Dad, how did you lose your legs?’” said Brix.

Photo: AFP

After the 1950s, marked in West Germany by the strong desire to leave the past behind, the 1960s saw a tentative dialogue begin in many families, with young people demanding explanations from their parents.

Brix also mustered the courage to ask questions but did not get straight answers. She continued to believe that her father only worked as a doctor for the Wehrmacht, Germany’s regular wartime army. It was long after her father’s death in 1980 that a corner of the veil over his past lifted.

“It was just before I retired in 2006,” Brix recalled, her throat tight with emotion. “A historian friend, who was researching the Nazis in the Baltics, asked me, ‘Barbara, did you know that your father was a member of the Einsatzgruppen?’ It was naturally a shock,” she said.

Brix knew only bits of her father’s biography: Peter Kroeger, a native of Latvia’s German minority, joined the Nazi party in 1933 at the age of 21.

Having become a doctor, Kroeger entered the party’s military branch, the Waffen-SS, and in June 1941, when Adolf Hitler launched the invasion of the Soviet Union, he left his pregnant wife alone to go to the Eastern front.

‘DENAZIFICATION

The Nuremberg trials of top Nazis, whose 75th anniversary Germany is commemorating this year, marked the country’s first broad social reckoning with the war and its crimes. But most of those responsible for atrocities were never prosecuted in a West Germany at the forefront of the Cold War, the Allies being more concerned about the Soviet threat than past abominations.

Kroeger was questioned as a witness several times in the 1960s, without ever being personally worried about facing consequences, Brix learned from Germany’s Central Office for the Investigation of Nazi Crimes.

In colored filing cabinets, she has stored the documents collected over the years, notably from the federal archives, on Dr Kroeger: a certificate of belonging to the SS, stamped with the eagle and the Nazi swastika, a certificate of “denazification,” which allowed him to continue his profession.

In one photo, her father poses in the black uniform of the SS.

The Nazi death squads he joined were deployed in the wake of the German troops invading the vast territory of the Soviet Union. Four Einsatzgruppen or “task forces” alone would annihilate some 1.5 million Jews, even before the construction of the extermination camps in occupied Poland. The first pogroms committed by Baltic and Ukrainian auxiliaries, supervised by the SS, shot groups of men, women and children and buried them in giant pits. Trucks outfitted with mobile gas chambers were later used to kill more efficiently.

‘FIRST PROOF’

Brix has tried to trace the genocidal journey of Einsatzgruppe C and find out if her own father may have participated in atrocities.

“He must have known about the persecution [of Jews], but I could not imagine that my father, a doctor, could have been present at a mass killing,” she said.

It took a Dutch journalist researching Reinhard Heydrich, one of the architects of the Holocaust, to shed more light.

“He pulled a document in English from his briefcase. Then I saw my father’s full name,” Brix said. “This was the testimony of the commander of Commando 5 of the Einsatzgruppe C, who recounted the first large mass killing in Kiev.

“The commander said he tried to refuse to take part but it was impossible. So he said he called the doctor, my father, to make sure that everything would happen in a ‘hygienic’ and orderly way,” Brix added.

This was how she received the “first proof” that her father attended at least one mass killing. Brix also knows that her father was present in Kiev during the Babi Yar ravine massacre.

More than 33,000 Jews were executed Sept. 29-30, 1941 in the Ukrainian capital in what many historians call the largest single bloodbath of the Holocaust.

However she is unsure if he was at the scene of the crime.

The former teacher has in her twilight years intensified her research on World War II.

She is active in Germany’s “remembrance culture” in which the past is explored as a means of atoning for past crimes and teaching younger generations to learn history’s dark lessons. Brix is also part of a Franco-German association that brings together the descendants of Nazis and resistance fighters to do outreach in schools in the two countries.

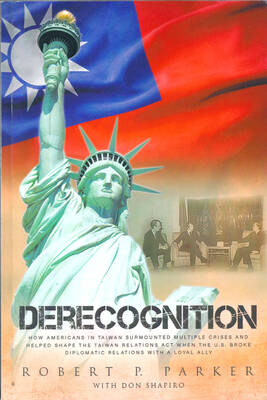

One of the biggest sore spots in Taiwan’s historical friendship with the US came in 1979 when US president Jimmy Carter broke off formal diplomatic relations with Taiwan’s Republic of China (ROC) government so that the US could establish relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Taiwan’s derecognition came purely at China’s insistence, and the US took the deal. Retired American diplomat John Tkacik, who for almost decade surrounding that schism, from 1974 to 1982, worked in embassies in Taipei and Beijing and at the Taiwan Desk in Washington DC, recently argued in the Taipei Times that “President Carter’s derecognition

This year will go down in the history books. Taiwan faces enormous turmoil and uncertainty in the coming months. Which political parties are in a good position to handle big changes? All of the main parties are beset with challenges. Taking stock, this column examined the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) (“Huang Kuo-chang’s choking the life out of the TPP,” May 28, page 12), the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) (“Challenges amid choppy waters for the DPP,” June 14, page 12) and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) (“KMT struggles to seize opportunities as ‘interesting times’ loom,” June 20, page 11). Times like these can

June 23 to June 29 After capturing the walled city of Hsinchu on June 22, 1895, the Japanese hoped to quickly push south and seize control of Taiwan’s entire west coast — but their advance was stalled for more than a month. Not only did local Hakka fighters continue to cause them headaches, resistance forces even attempted to retake the city three times. “We had planned to occupy Anping (Tainan) and Takao (Kaohsiung) as soon as possible, but ever since we took Hsinchu, nearby bandits proclaiming to be ‘righteous people’ (義民) have been destroying train tracks and electrical cables, and gathering in villages

Dr. Y. Tony Yang, Associate Dean of Health Policy and Population Science at George Washington University, argued last week in a piece for the Taipei Times about former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) leading a student delegation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that, “The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world” (“Ma’s Visit, DPP’s Blind Spot,” June 18, page 8). Yang contends that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has a blind spot: “By treating any