A critically acclaimed family drama about Korean immigrants in the US is being touted as an Oscar contender after “Parasite” broke down barriers to non-English-language movies winning the highest-profile accolades.

Based on Korean-American director Lee Isaac Chung’s own experiences growing up in rural America in the 1980s, Minari won both the audience and grand jury prizes for US dramas at this year’s Sundance Film Festival.

After a sold-out Asian premiere last week at the Busan film festival, Asia’s largest, Hollywood trade outlet Variety reported the film’s stars — including Korean-American actor Steven Yeun — will campaign for acting categories at the Academy Awards.

Photo: YouTube screen grab

But the critical success of Minari comes with Asian-American experience still vastly underrepresented in Hollywood, which has generally preferred to focus on Americans’ experiences of Asia, particularly in war, or Asian-set fantasies such as Mulan.

The slew of awards for Parasite represented a nod towards international diversity, said Brian Hu, a film professor at San Diego State University, “not American diversity, which still requires a lot more work.”

“It would be hugely historical for a Korean American film to be nominated” for the Oscars, he said.

Photo: YouTube screen grab

Despite their shared Korean roots, the two movies are very different: Minari is an American film shot almost entirely in Korean, featuring Asian-American experiences, while Parasite, a dark parable about the gulf between rich and poor in Seoul, was solely a South Korean production.

CHILDHOOD REVISITED

Minari stars Yeun — best known for his role in the Walking Dead zombie television series — as Jacob, a young, Korean-born father who moves his family to an all-white town in rural Arkansas in pursuit of a better life.

Photo: YouTube screen grab

He wants to start his own farm but his wife is skeptical and feels isolated, while their seven-year-old son, David — a character inspired by director Chung’s younger self — finds himself increasingly torn between two cultures. Yeun is renowned for his bilingual talent, receiving a best supporting actor prize from the Los Angeles Film Critics Association for his Korean-language performance in the acclaimed thriller, Burning.

In Minari, Yeun often speaks Konglish, a style of sometimes-broken English used by Korean speakers, for which he said he channeled his own immigrant parents who took him to the US when he was five. The film reflected his own experience growing up as an immigrant in Michigan, he said, especially “this feeling of belonging nowhere, just caught in between the gaps of places”.

“You’re not Korean. You are not American. You kind of just fit in this weird space where you don’t feel grounded anywhere,” he told an online press conference at the Busan festival. “It reminds me of my family and why we, you know, held each other so tight because that’s all we really had.”

‘STEREOTYPICAL REPRESENTATIONS’

The four Oscars for Parasite included Best Picture and Best Director, but nominations for any of the Minari actors would be the first for any Korean in the performance categories at the Academy Awards.

Film experts and activists say there has been very limited Asian-American presence in Hollywood, with many Asian roles even played by white actors.

In one notorious example of “yellowface,” Luise Rainer won the 1937 Best Actress Oscar for playing a Chinese character in The Good Earth. More recently, the casting of Emma Stone as a part-Hawaiian, part-Chinese character in 2015’s Aloha sparked controversy.

“Talented Asian and Asian-American actors have existed since the silent film era,” said Terry K Park, a lecturer in Asian American Studies at the University of Maryland, College Park.

“But they haven’t been given the same opportunities to inhabit even stereotypical representations of their own identities, let alone complex ones.”

But films like Parasite and Minari could open doors to other subtitled movies and actors of Asian descent, experts say.

It was “extremely curious that Hollywood, located in LA, with a significant presence of Asian Americans, so long denied their very existence,” said John Lie, a sociology professor at the University of California, Berkeley. The mainstream US “dream factory” clung on to “an older vision of America long after it was relevant”, he said, while cable TV dramas have become “not only more interesting but also more multiethnic”. “So Hollywood is belatedly catching up.”

When Taiwan was battered by storms this summer, the only crumb of comfort I could take was knowing that some advice I’d drafted several weeks earlier had been correct. Regarding the Southern Cross-Island Highway (南橫公路), a spectacular high-elevation route connecting Taiwan’s southwest with the country’s southeast, I’d written: “The precarious existence of this road cannot be overstated; those hoping to drive or ride all the way across should have a backup plan.” As this article was going to press, the middle section of the highway, between Meishankou (梅山口) in Kaohsiung and Siangyang (向陽) in Taitung County, was still closed to outsiders

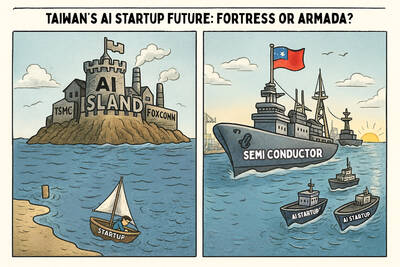

President William Lai (賴清德) has championed Taiwan as an “AI Island” — an artificial intelligence (AI) hub powering the global tech economy. But without major shifts in talent, funding and strategic direction, this vision risks becoming a static fortress: indispensable, yet immobile and vulnerable. It’s time to reframe Taiwan’s ambition. Time to move from a resource-rich AI island to an AI Armada. Why change metaphors? Because choosing the right metaphor shapes both understanding and strategy. The “AI Island” frames our national ambition as a static fortress that, while valuable, is still vulnerable and reactive. Shifting our metaphor to an “AI Armada”

US President Donald Trump may have hoped for an impromptu talk with his old friend Kim Jong-un during a recent trip to Asia, but analysts say the increasingly emboldened North Korean despot had few good reasons to join the photo-op. Trump sent repeated overtures to Kim during his barnstorming tour of Asia, saying he was “100 percent” open to a meeting and even bucking decades of US policy by conceding that North Korea was “sort of a nuclear power.” But Pyongyang kept mum on the invitation, instead firing off missiles and sending its foreign minister to Russia and Belarus, with whom it

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has a dystopian, radical and dangerous conception of itself. Few are aware of this very fundamental difference between how they view power and how the rest of the world does. Even those of us who have lived in China sometimes fall back into the trap of viewing it through the lens of the power relationships common throughout the rest of the world, instead of understanding the CCP as it conceives of itself. Broadly speaking, the concepts of the people, race, culture, civilization, nation, government and religion are separate, though often overlapping and intertwined. A government