The men in the audience clapped and the women ululated as the band finished singing: it would have been commonplace except the venue was in Iran and the group on stage were all women.

The catchy rhythmic music they played that balmy night is known as bandari.

Its lyrics are from ancient folkloric songs, passed down the generations and familiar to many at the concert in an amphitheater in the southern port of Bandar Abbas.

Photo: AFP

Only this time, it was being performed by women in front of a mixed crowd.

“It feels as if you have been seen at last” by “a new part of society,” said band member Noushin Yousefzadeh, who plays the oud, the Middle Eastern lute. “All that training has paid off at last.”

Dressed in traditional clothing, the band was taking part in a state-organized festival to showcase “Persian Gulf music” and, as well as singing, also played their instruments.

Photo: AFP

Before long, the audience was ecstatically singing along with the four-piece band.

Such public expressions of joy are usually frowned upon by officials in Iran, which has been under strict Islamic rule for more than 40 years.

Formed in late 2016 after a conversation at the beach between two of the women, the band is called Dingo, which in the local dialect refers to the first wobbly steps taken by infants.

Photo: AFP

The show — staged last year — was only the second time they had performed in front of a mixed audience.

The first occasion was at the Shiraz Oud Festival in July 2018.

“These festivals are a great opportunity because in normal circumstances we cannot sing in front of men,” said drummer Faezeh Mohseni.

MANY RESTRICTIONS

When performing for all-female audiences, Mohseni sings solo.

But, informed only a few days before the festival that they had been selected and would be singing to both men and women, the band hastily re-arranged its routine.

“We had to spend all those days rehearsing so that all of us could sing in chorus,” said Malihe Shahinzadeh, who plays the pippeh, a type of local drum.

Public singing by women is not a clear-cut affair in the Islamic republic.

No law specifically forbids it, according to Sahar Taati, a former director at the music department of Iran’s Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance, known as Ershad.

Nonetheless, most clerics believe that the sound of female singing is haram — or forbidden — because it can be sensuously stimulating for men and lead to depravity, she added.

Secular music is generally frowned upon by Shiite clergy, who see it as entertainment that distracts from religion.

Its ban, decreed soon after the 1979 Islamic revolution, was gradually lifted, firstly for “revolutionary” music, meant to galvanize troops in the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq war.

Then, the emphasis was put on traditional Iranian music, in contrast to western variants deemed “decadent” by the authorities, who waged a war against “cultural invasion”.

After moderate Hassan Rouhani was elected president in 2013, succeeding ultraconservative Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, staging musical events became somewhat easier.

There are, however, still a myriad of restrictions. Ershad must approve concerts and it remains almost impossible for a female singer to perform alone, except in front of other women.

But “women can sing to mixed audiences if two or more women sing together, or a female solo singer is accompanied by a male singer whose voice is always at least as strong as hers,” said Taati.

That’s how a Persian adaptation of the musical Les Miserables was performed in Tehran in the winter of 2018-2019, with female solos supported by the voice of another singer in the wings.

BANDARI ABROAD

The members of Dingo, who are all in their mid-20s to mid-30s, had tried a number of times to arrange performances for mixed audiences themselves.

But it was difficult to coordinate and in the end “we just gave up,” said Negin Heydari, a former member, who plays the kasser, a smaller drum usually played together with the dohol and pippeh.

So now, whenever authorities arrange festivals and shows like this one in their home town, they apply and hope they will be selected, even if it means not knowing until the last minute if they have been.

But, the exhilaration of playing for mixed audiences is worth all the uncertainty and long hours of practice — in the “Dingo room”, a sound-proof den in the courtyard of one of their parents’ homes.

Heydari described how happy her husband of 10 years, Sassan, said he was to be able to see her perform live on stage at last.

The four musicians, two of whom have jobs, feel fully supported by their families and have many dreams for their band, from more performances inside Iran, to playing at venues abroad.

“We want to make Dingo international,” said Mohseni, while Shahinzadeh is eager for the rest of the world to hear the music of her hometown.

Their dedication paid off when they won a jury prize for their performance at last year’s festival, where they wore colorful outfits with sequins and gold embroidery, traditionally worn in southern Hormozgan province.

Since the concert, Negin Heydari has left the band because of “artistic differences”, and her place has been taken by guitarist Mina Molai.

Meanwhile, the COVID-19 pandemic, which has hit Iran particularly hard, has left a mark on Dingo’s progress in good and bad ways.

It has dampened the band’s hopes of recording an album and prevented rehearsals but also given rise to new ideas.

“The period of confinement has been an opportunity for me to research the music of our region and also to improve my playing technique,” said Shahinzadeh.

“Up until now, we’ve only been doing covers of the bandari folk repertoire, but now we’re thinking of creating original pieces,” she said.

TAXIS AND USBS

Despite the religious limitations, female solo singing can still be heard by men in Iran, especially if you catch a taxi in the capital, Tehran.

You may well come across a driver who plays Googoosh, a pre-revolution pop diva, who reemerged in North America in 2000 after years of silence in her homeland.

Another might reach for a USB memory stick with songs by the late sisters Hayedeh and Mahasti, icons of the music scene before 1979 who are buried in California.

You could also hear Gelareh Sheibani, a young songstress based on the US west coast whose tunes are finding their way to Iran over the internet.

That’s unless your cabbie prefers the Paris-based soprano Darya Dadvar, one of the few women to have sung solo in front of a mixed audience since the revolution.

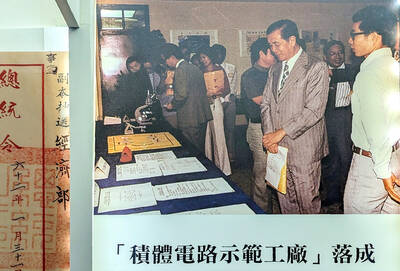

Oct. 27 to Nov. 2 Over a breakfast of soymilk and fried dough costing less than NT$400, seven officials and engineers agreed on a NT$400 million plan — unaware that it would mark the beginning of Taiwan’s semiconductor empire. It was a cold February morning in 1974. Gathered at the unassuming shop were Economics minister Sun Yun-hsuan (孫運璿), director-general of Transportation and Communications Kao Yu-shu (高玉樹), Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) president Wang Chao-chen (王兆振), Telecommunications Laboratories director Kang Pao-huang (康寶煌), Executive Yuan secretary-general Fei Hua (費驊), director-general of Telecommunications Fang Hsien-chi (方賢齊) and Radio Corporation of America (RCA) Laboratories director Pan

The classic warmth of a good old-fashioned izakaya beckons you in, all cozy nooks and dark wood finishes, as tables order a third round and waiters sling tapas-sized bites and assorted — sometimes unidentifiable — skewered meats. But there’s a romantic hush about this Ximending (西門町) hotspot, with cocktails savored, plating elegant and never rushed and daters and diners lit by candlelight and chandelier. Each chair is mismatched and the assorted tables appear to be the fanciest picks from a nearby flea market. A naked sewing mannequin stands in a dimly lit corner, adorned with antique mirrors and draped foliage

The consensus on the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) chair race is that Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) ran a populist, ideological back-to-basics campaign and soundly defeated former Taipei mayor Hau Lung-bin (郝龍斌), the candidate backed by the big institutional players. Cheng tapped into a wave of popular enthusiasm within the KMT, while the institutional players’ get-out-the-vote abilities fell flat, suggesting their power has weakened significantly. Yet, a closer look at the race paints a more complicated picture, raising questions about some analysts’ conclusions, including my own. TURNOUT Here is a surprising statistic: Turnout was 130,678, or 39.46 percent of the 331,145 eligible party

The election of Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) as chair of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) marked a triumphant return of pride in the “Chinese” in the party name. Cheng wants Taiwanese to be proud to call themselves Chinese again. The unambiguous winner was a return to the KMT ideology that formed in the early 2000s under then chairman Lien Chan (連戰) and president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) put into practice as far as he could, until ultimately thwarted by hundreds of thousands of protestors thronging the streets in what became known as the Sunflower movement in 2014. Cheng is an unambiguous Chinese ethnonationalist,