More than a decade ago, Ho Hsiao-mei (何曉玫), a professor at Taipei National University of the Arts (TNUA, 國立臺北藝術大學) and an award-winning choreographer, had the idea that local dance fans, families and friends should be able to see the work of Taiwanese professionals who have made their careers with companies abroad — without having to travel far themselves.

What she came up with was the “Meimage Dance New Choreographer Project” (鈕扣New Choreographer 計畫), a platform run under her own dance troupe, which would produce a showcase once a year featuring works choreographed and danced by expats home on their annual vacations.

It was natural, of course, that many of these, if not the majority, would be people that Ho knew from TNUA, either graduates or those who had studied for a while at the university, but over the years the programs have also featured collaborations with Taiwan-based designers or artists as well as some foreign artists — which helped forged connections for future partnerships.

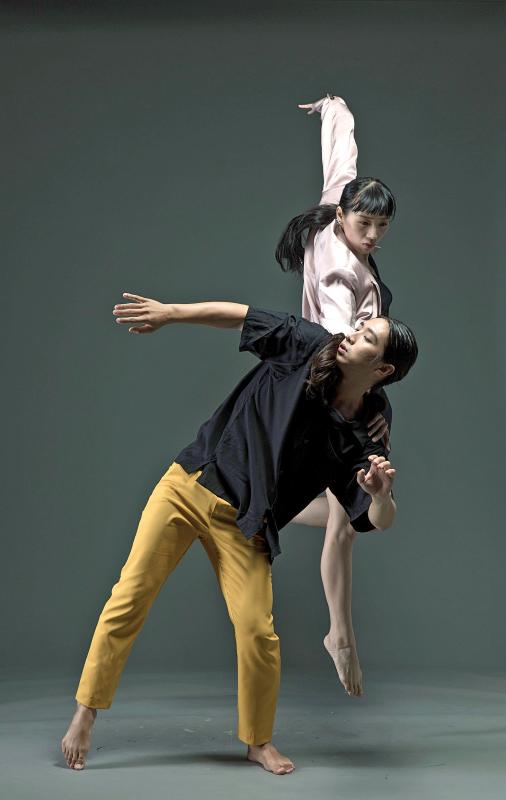

Photo courtesy of Terry Lin

One of her original aims with the project was to bring dancers working overseas and those in Taiwan closer.

She has definitely succeeded, although sometimes in unexpected ways. For example, Romanian dancer/choreographer Constantin Georgescu came with Yuan Shang-jen (袁尚仁) to perform in Yuan’s Dialogue (對話) for the 2013 edition, and since then has become a regular collaborator with the Kaohsiung City Ballet (KCB, 高雄城市芭蕾舞團).

To celebrate the platform’s 10th anniversary, Ho and her team are presenting three programs over the course of this weekend and next, programs that were both shaped and inspired by the COVID-19 pandemic — as well as technology — that are altering the world we live in.

Photo courtesy of Terry Lin

Asked if she had thought when she started the platform that it would prove to be an annual hit, Ho said “never.”

“Honestly never thought about it, and then this year, I just thought: ‘Wow,’” she said in a telephone interview on Wednesday.

“For the first 10 years, I invited dancers who would be coming back [anyway] — this way we don’t have to pay for airfare — and we were doing this for the local audiences,” she said before adding that looking toward the next 10 years she might make some changes, as “the whole environment, the whole situation is changing, there are more opportunities, more financing for us to do things.”

Photo courtesy of Terry Lin

The first set of shows at the Umay Theater in Huashan 1914 Creative Park (華山1914文化創意產業園區) this weekend consist of four pieces, each by a pair of dancers, one locally based and the other overseas, creating a dialogue based on their different experiences, Ho said.

“When this [COVID-19] started, I talked to the dancers about what do we do if we cannot go out or come back,” she said, adding that this became the theme for the works.

In some ways the pandemic has highlighted a common problem that Taiwanese dancers face, she said. Those working abroad might want to come back, but wonder if they can make a living, while local groups might want to go out and perform abroad, but face financial and logistical difficulties.

However, the pandemic did make this year’s production more difficult, not just due to travel restrictions, but because some of the dancers who might have wanted to come home this summer could not adjust their schedules to allow for a 14-day quarantine on either side of their trip.

The solution was technology: not only did the partnerships use various social media apps to collaborate via the Internet, some will be performing live onscreen with their partners during the shows.

Ho was also inspired to use the Internet to broaden the platform’s audience base, reaching out to dance groups in southern Taiwan, Singapore and Australia, with invitations to use livestreaming to see the shows.

Originally she wanted to include a projection system in the theaters so that the performers and audiences in Taipei could also see the viewers in other places, “but we didn’t have enough money to do it,” she said.

The idea of not having live performances this year was never an option, she just wanted to open the doors for more Internet audiences.

“Live performance is the most important thing,” she said. “But maybe through these connections we can build more connections with dance groups elsewhere.”

This weekend’s shows, subtitled Shuangpaikou (雙排扣, double-breasted), have been divided into Program A and Program B, each featuring two pairs of works, and with each program presented twice.

The choreographers are a mix of old and new faces, or in one case, a very familiar face in a new role.

“I put them [the partnerships] together. Some really melded, with other pairs, each did basically their own thing,” Ho said.

Program A, which will be performed at 6pm each day, features Fajiao zhong (發酵中, fermenting), a work-in-progress by Chou Chang-ning (周章佞) and Lin Yen-ching (林燕卿), and Yishi (遺室, old buildings) by Wally Hsu Cheng-wei (許程崴) and Hung Tsai-hsi (洪綵希).

Program B, which will be performed at 8pm, features Ameizi yu zhenjie (阿媚仔與珍姐, A-Meizi and Zhenjie) by Su Pin-wen (蘇品文) and Tung Po-lin (董柏霖), and Shenghuo jilu (生活紀錄, record of a life) by Lin Ju-ju (林祐如) and Liang Shih-huai (梁世懷).

On Saturday and Sunday next week, the action shifts to the National Experimental Theater, for a show subtitled Kou zuoban (扣作伴, fastened together), featuring The Passing Measures, choreographed by the husband and wife team of Vakulya Zoltan and Lee Chen-wei (李貞葳), and Elysium (極樂世界), choreographed by Tu Lee-yuan and set on three dancers.

Ho said that she had been surprise by how well the pairings have turned out, given that some of the dancer/choreographers have very different backgrounds in terms of dance styles and career choices.

One example she cited was Chou, who retired after 25 years with the Cloud Gate Dance Theatre (雲門舞集), whom she paired with Lin Yen-ching, an original member of Brighton, England-based Hofesh Shechter Company before joining the London-based Akram Khan Company, where she still works as a rehearsal director.

“Yen-ching and Chang-ning are so different. At this point in time Chang-ning has dramatically changed, she was used to working with the same choreographer ... I think she has been asking ‘who am I, what can I dance,’ while Yin-ching is constantly changing, she is not satisfied with working with the same choreographers over and over again, that is just the kind of person she is,” Ho said.

The other participants range from freelancers, to members of classical or contemporary ballet troupes, to those who have founded their own companies. Some have appeared in earlier Next Choreographer Project shows, others are making their first appearance.

Newcomer Wally Hsu founded Hsu Chen Wei Dance Company (許程崴製作舞團) in 2016, while New York City-based Hung, who was in the 2016 show, has worked with the Australian Dance Theater, Tasdance and Chunky Move Dance Company, and is now a member of the contemporary troupe Abarukas.

Tung, a former dancer with London-based Company Wayne McGregor, was in the 2017 show and was paired with newbie Su, who has worked as a freelance dancer as well as being artistic director of Kua Bo Dance Theatre (看嘸舞蹈劇場).

Lin Ju-ju is another newbie freelancer with a contemporary background, while her collaborator Liang, who was in last year’s show, is a classically trained soloist with the Seoul-based Universal Ballet … and he will be making a virtual appearance this year.

Lee, who was in the first production in 2011 and then appeared again in 2014, is a Batsheva Dance Company alumnus turned freelancer who now works with Voetvolk Lisbeth Gruwez in Brussels, as well as her husband, Hungarian dancer/actor Zoltan. She could not make it back to Taipei, so Zoltan will be dancing their piece with Hung Peiyu (洪佩瑜) while Lee appears on screen.

Tu Lee-yuan, formerly with GoteborgsOperans Danskompani in Sweden, was in the 2017 platform, and this year is the only one to create a piece for other dancers while staying off-stage himself.

“He came in January to audition dancers, and then came back in June or early July to work with them,” Ho said, referring to Liang Jing-yu (梁淨喻), Hsieh Chih-ying (謝知穎) and Tseng Luo-ting (曾淯婷).

All of the works required dialogue — in the creation process and with their audiences — and Ho said they will hopefully form part of a new dialogue about the relationship between dance and other arts with society.

After all, “the most important thing about dance is sharing,” she said.

Tickets for tomorrow’s shows are sold out, but there are still some seats for Program B at 8pm on Sunday, as well as next weekend’s shows.

One of the biggest sore spots in Taiwan’s historical friendship with the US came in 1979 when US president Jimmy Carter broke off formal diplomatic relations with Taiwan’s Republic of China (ROC) government so that the US could establish relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Taiwan’s derecognition came purely at China’s insistence, and the US took the deal. Retired American diplomat John Tkacik, who for almost decade surrounding that schism, from 1974 to 1982, worked in embassies in Taipei and Beijing and at the Taiwan Desk in Washington DC, recently argued in the Taipei Times that “President Carter’s derecognition

This year will go down in the history books. Taiwan faces enormous turmoil and uncertainty in the coming months. Which political parties are in a good position to handle big changes? All of the main parties are beset with challenges. Taking stock, this column examined the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) (“Huang Kuo-chang’s choking the life out of the TPP,” May 28, page 12), the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) (“Challenges amid choppy waters for the DPP,” June 14, page 12) and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) (“KMT struggles to seize opportunities as ‘interesting times’ loom,” June 20, page 11). Times like these can

June 23 to June 29 After capturing the walled city of Hsinchu on June 22, 1895, the Japanese hoped to quickly push south and seize control of Taiwan’s entire west coast — but their advance was stalled for more than a month. Not only did local Hakka fighters continue to cause them headaches, resistance forces even attempted to retake the city three times. “We had planned to occupy Anping (Tainan) and Takao (Kaohsiung) as soon as possible, but ever since we took Hsinchu, nearby bandits proclaiming to be ‘righteous people’ (義民) have been destroying train tracks and electrical cables, and gathering in villages

Dr. Y. Tony Yang, Associate Dean of Health Policy and Population Science at George Washington University, argued last week in a piece for the Taipei Times about former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) leading a student delegation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that, “The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world” (“Ma’s Visit, DPP’s Blind Spot,” June 18, page 8). Yang contends that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has a blind spot: “By treating any