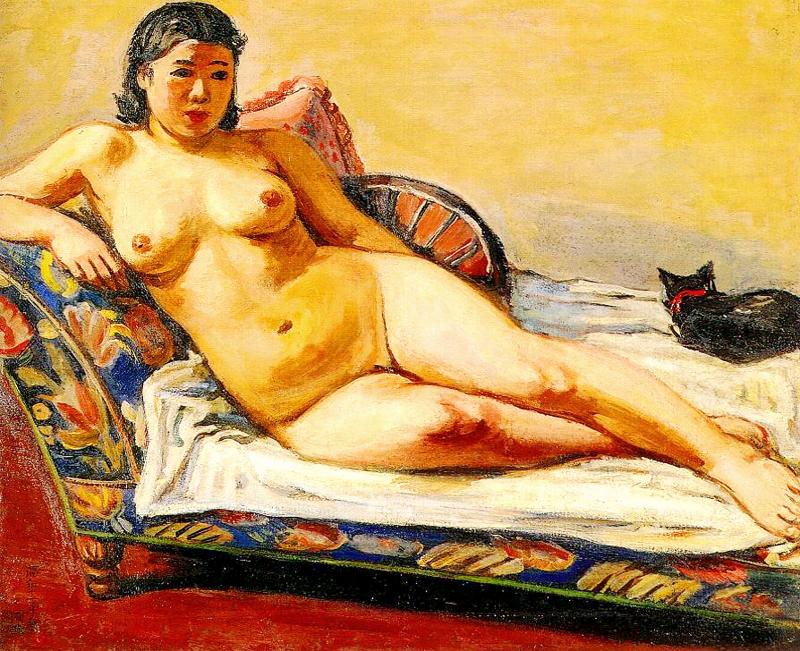

Taiwan’s artist community was outraged when the authorities banned Lee Shih-chiao’s (李石樵) Reclining Nude (橫臥裸婦) from the 1936 Taiyang Art Exhibition (台陽美術展覽會).

The Taiwan Daily News (台灣日日新報) reported that after hours of deliberation, the officials censored the piece for “contravening public morals.”

Although the government did have rules on publicly displaying nude art, the state-run Taiwan Fine Art Exhibition regularly featured naked women, allowing more revealing pieces each year. On the same page, the newspaper ran a scathing criticism of the decision by an anonymous artist.

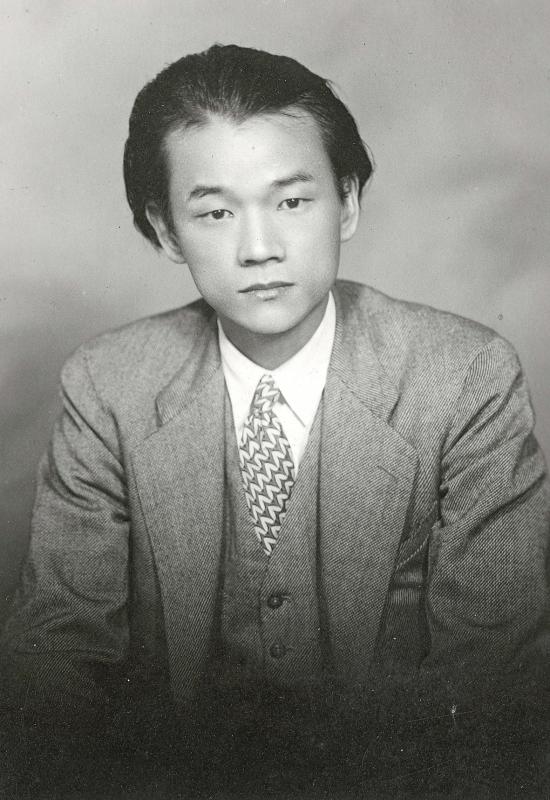

Photo courtesy of Lee Shih-chiao Art Museum

“This is completely laughable … If they really thought [Reclining Nude] contravened public morals, they should clearly point out why. If someone feels that such imagery incites lewd thoughts, it just means that they already had a dirty mind. If this painting cannot be exhibited, that means all the famous nude paintings should all be accused of obscenity! I feel that this incident is blasphemous toward art itself, and will hamper the development of Taiwan’s art scene,” the artist wrote.

The colonial authorities declined to comment. The kerfuffle actually boosted public interest in the exhibition, and crowds packed the halls for its entire duration.

Lee, who was born on July 13, 1908, was a recent graduate of the Tokyo School of Fine Arts then, but he would go on to become one of Taiwan’s most influential painters.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

ACCEPTANCE OF NUDITY

While the nude figure had been a staple of Western art since antiquity, in Asia it was still considered obscene to publicly display such artwork up to the late 19th century.

The first time nude art caused a stir in Japan was in 1896, when Seiki Kuroda exhibited a life-size portrait of a woman he completed while studying in France. Critics slammed the piece as corrupting social mores, and a livid Kuroda declared that Japan’s art scene would never be respected by the world with such backward attitudes. Since the country was in the middle of its modernization process, Kuroda’s argument won. By the time of the launch of the Imperial Art Exhibition in 1919, nude paintings were a common sight.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

By contrast, Taiwanese society remained conservative even under Japanese rule. The first notable nude piece by a local artist was Huang Tu-shui’s (黃土水) Sweet Dew (甘露水), which was selected to the Imperial Art Exhibition in 1921 and featured in the Taiwan Daily News (台灣日日新報).

Chen Meng-fan (陳孟凡) writes in The Social Problem of Female Nude Paintings in the Public during the Japanese Colonial Period (日治時期裸體畫公開化的社會爭議) that society in general saw the nude figure as something deeply private.

“It should never be shown in public, nor did it have any artistic or aesthetic value. Anything that showed naked women was considered pornography,” Chen writes.

While nude pieces were not exhibited in Taiwan initially, local papers would include them in their reports about the Imperial Fine Arts Exhibition, which directly conflicted with Taiwanese social values, Chen writes.

In 1907, the colonial police promulgated regulations regarding nude art, noting that “Taiwan’s customs and values are different, and the policy should be adapted to local conditions … Whether a nude piece is harming social mores should be judged by whether it inspires lewd and inappropriate thoughts in the viewer.”

The regulations banned art depicting sexual acts, art that showed private areas from any angle and art that depicted naked figures in positions that even suggested the position of their genitals.

In 1925 and 1926, Japanese art critic Shunkichi published several op-eds in the Taiwan Daily News arguing that such conservative attitudes will stunt the development of art appreciation among Taiwanese, which directly conflicted with the colonial government’s aim to “educate” and raise the cultural level of their subjects.

The government launched the Taiwan Fine Arts Exhibition in 1927. Although the government explicitly forbade any art that “undermined public morality,” four nude pieces made the cut for the inaugural show at Kabayama Elementary School (today’s National Police Agency headquarters).

The subjects in all four paintings covered their private parts with either a towel or their hands, or just featured their backs. However, an article in the Taiwan Daily News noted that the police rejected at least one overly-revealing nude painting.

Each subsequent show included at least one nude piece. Chen writes that the artists became bolder as time went on, continuously submitting pieces that challenged the regulations. This prompted the authorities to reiterate the rules after the 1930 exhibition, but the ban was evidently much looser as two artworks in the 1936 exhibition clearly showed the subjects’ private areas.

POLITICAL MOVE?

In 1934, local artists and intellectuals formed the Taiyang Art Research Association (臺陽美術協會) and launched their own annual exhibition. The founding members included heavyweights such as Chen Cheng-po (陳澄波), Lee Mei-shu (李梅樹) and Yang San-lang (楊三郎). Lee Shih-chiao was still in Japan at the time, but he was closely involved with the association and submitted works to their shows.

The artists were puzzled as to why Lee’s painting was rejected. Although it did technically breach the regulations by showing the subject in full frontal nudity, those rules had long been relaxed, and more explicit works had been allowed into the Taiwan Fine Art Exhibition.

The subject’s reclining position, which the officials cited as one of the reasons for rejecting it, didn’t appear to be the real problem either. Between 1927 and 1935, the state-run art show featured nine paintings with naked or semi-naked women in the same pose.

Chen writes that the censorship was most likely due to political factors. Although some experts maintain that Taiyang was purely an art organization, others, such as artist Hsieh Li-fa (謝里法) believed otherwise.

“The Taiyang Exhibition enables Taiwanese to look at Taiwanese art from their own perspective, rather than from the Japanese point of view via the Taiwan Fine Arts Exhibition,” a character states in Hsieh’s novel, La Grande Chaumiere Violette (紫色大稻埕), “Taiwanese must have autonomy over their own aesthetics, so they can control their cultural lifeline. Only in this way do we have a future as a people.”

A 1934 Taiwan Daily News article about the launch of the Taiyang Exhibition stressed that it “was not founded to resist the Taiwan Fine Art Exhibition. It is meant to support the government effort and push Taiwan’s art scene forward together.”

But the fact that the Taiyang artists continued to make similar statements even in 1940 showed that the perception remained that they were trying to subvert government control of Taiwan’s art scene.

Furthermore, while the Taiwan Fine Art Exhibition’s judges were made up mostly of Japanese officials and artists, the Taiyang Exhibition was run entirely by Taiwanese. Chen says that the banning of Reclining Nude was likely a political statement by the authorities against Taiwanese trying to run their own show.

Proof that the censorship had nothing to do with obscenity was further cemented a few months later when the Taiwan Fine Art Exhibition displayed a painting by Ryuzaburo Umehara depicting a naked woman in almost the exact same position.

Lee went on to have a long career before he died in 1995, painting countless more nude women without further issue.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Jacques Poissant’s suffering stopped the day he asked his daughter if it would be “cowardly to ask to be helped to die.” The retired Canadian insurance adviser was 93, and “was wasting away” after a long battle with prostate cancer. “He no longer had any zest for life,” Josee Poissant said. Last year her mother made the same choice at 96 when she realized she would not be getting out of hospital. She died surrounded by her children and their partners listening to the music she loved. “She was at peace. She sang until she went to sleep.” Josee Poissant remembers it as a beautiful

For many centuries from the medieval to the early modern era, the island port of Hirado on the northwestern tip of Kyushu in Japan was the epicenter of piracy in East Asia. From bases in Hirado the notorious wokou (倭寇) terrorized Korea and China. They raided coastal towns, carrying off people into slavery and looting everything from grain to porcelain to bells in Buddhist temples. Kyushu itself operated a thriving trade with China in sulfur, a necessary ingredient of the gunpowder that powered militaries from Europe to Japan. Over time Hirado developed into a full service stop for pirates. Booty could

Lori Sepich smoked for years and sometimes skipped taking her blood pressure medicine. But she never thought she’d have a heart attack. The possibility “just wasn’t registering with me,” said the 64-year-old from Memphis, Tennessee, who suffered two of them 13 years apart. She’s far from alone. More than 60 million women in the US live with cardiovascular disease, which includes heart disease as well as stroke, heart failure and atrial fibrillation. And despite the myth that heart attacks mostly strike men, women are vulnerable too. Overall in the US, 1 in 5 women dies of cardiovascular disease each year, 37,000 of them

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades