It’s impossible to write a book entirely in the Taokas language. There are only about 500 recorded words in the indigenous tongue, whose speakers shifted to Taiwanese generations ago while preserving certain Taokas phrases in their speech.

“When I first started recording the language around 1997, I really had to jog the memories of the elders to find anything,” says Liu Chiu-yun (劉秋雲) a member of the Taokas community and a language researcher.

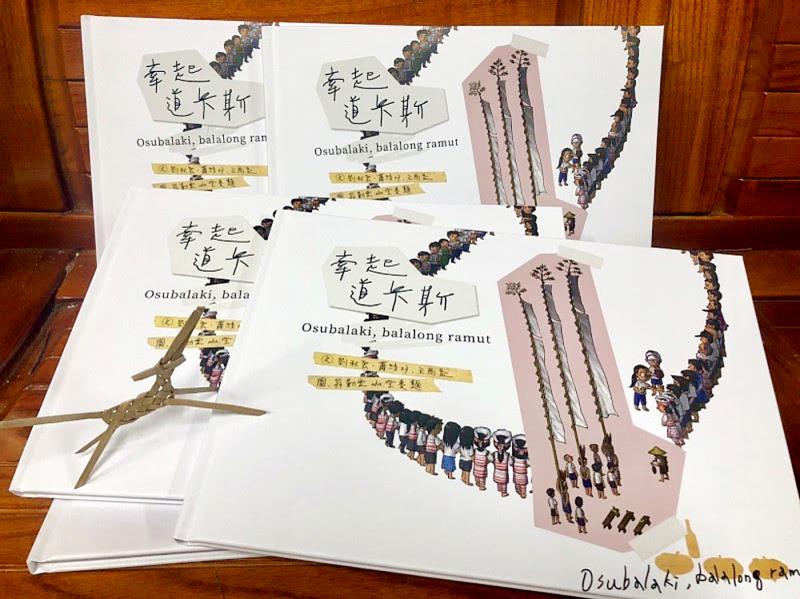

The Taokas last month unveiled a picture book, Osubalaki, Balalong Ramut the community’s first-ever commercial publication using the language. The lavishly illustrated book details their annual kantian festival, which was revived in 2002 after they stopped holding it in 1947 due to cultural suppression.

Photo courtesy of Weng Chin-wen

The main text is in Chinese and English, with Romanized Taokas words and dialogue sprinkled throughout. The book was gifted to all elementary and junior high schools in Miaoli as well as Singang (新港) residents. The Taokas are members of the Pingpu, or plains Aborigines, a community that has yet to be recognized by the government. They reside primarily in Miaoli and Nantou counties.

Kaisanan Ahuan, a Pingpu activist, says that many readers heard of his people for the first time through the book. He only learned that he was Taokas in college and has been studying the language for several years.

“It doesn’t matter if one can only speak simple phrases,” he says. “There’s a prayer during the kantian festival that must be recited in Taokas, otherwise we cannot proceed. It’s very important to us. And if people my age don’t use it, it will disappear.”

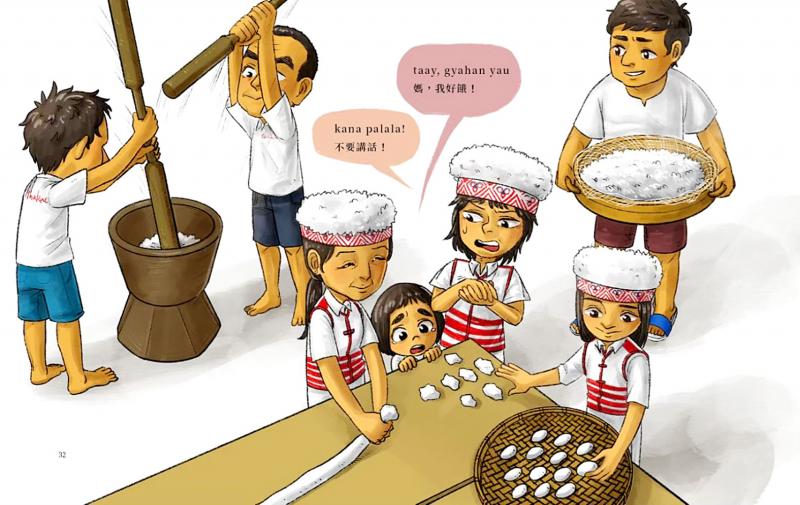

Photo courtesy of Weng Chin-wen

CULTURAL RESURRECTION

Kaisanan grew up in Puli Township (埔里) in Nantou County, where a significant number of Taokas migrated in the 1800s from their original homeland along the central coast. Aside from a few Taokas words he heard from elders, he knew nothing about his Taokas roots until he visited Singang in northern Miaoli, where the culture is better preserved.

Liu says the entire village spoke Hoklo when she was little, and although they would sprinkle Taokas into their speech, she didn’t know it was a different language.

Photo courtesy of Weng Chin-wen

“My aunt would say that my son is very obedient during long car rides and doesn’t samali (cry),” Liu says. “I thought that was Hoklo, but she was using Taokas.”

After recording what she could from elders, she began teaching it to whoever wanted to learn. However, because the Taokas have yet to gain official recognition, their language cannot be part of the public school curriculum.

In 2014, the Council of Indigenous Peoples began providing financial support to Pingpu groups to publish books in their own language. At first, the Taokas hung basic vocabulary signs around Singang, and in January last year the Taokas Cultural Association published its first dictionary.

Kaisanan, who heads the Central Taiwan Pingpu Indigenous Groups Youth Alliance, says the existence of Taokas is crucial to gaining recognition.

“Without [our own] language, it’s very hard to convince the government that we’re a separate group,” he says.

The book is a lively depiction of the preparations for the 2018 kantian festival. The most distinct feature are the male dancers with 30 meter-high bamboo flags tied to their backs. A few elders in the community even remember participating in it as children.

The book contains a photo from the Japanese colonial era of villagers posing with the giant flags. For many, it was the first time they had ever seen an image of the old festival. The authors found the photo in a book by late National Taiwan University anthropologist Hu Chia-yu (胡家瑜).

“Many people were quite moved when they saw the photo,” Liu says. “So the kantian that we heard elders speak of really did happen. Some villagers recognized people in the photo too.”

IMMERSIVE RESEARCH

Kaisanan says the Taokas chose the picture book format because it will appeal to a broader audience. The story revolves around the 2018 festival, so villagers will be familiar with it, as the illustrations accurately depict the real-life participants as well as local scenery.

Liu says that besides kantian, Taokas children have few opportunities or outlets to learn about their ancestral culture.

“It’s another way to preserve our language,” he says.

Before illustrating the book, Weng Chin-wen (翁勤雯) helped with the murals depicting traditional life that adorn the buildings and walls in Singang. She also completed a picture book in 2018 for the Pingpu Kahabu community’s muzaw a azem, a Lunar New Year festival.

For the Taokas project, Weng participated in the kantian festival and interviewed elders. But as a woman, she did not have access to certain preparations and rituals restricted to Taokas men.

Even Liu had never seen the complex process of tying the flagpoles to the dancers’ backs until she asked her cousin to film it for Weng last year. Using the footage, Weng repeatedly revised her illustrations until the elders deemed them accurate.

Kaisanan and Liu say they want to create more educational material in the future, partially to help their efforts to win government recognition.

“We hope that the government sees that we do have the resources and materials to teach [Taokas],” Kaisanan says.

Liu says she is happy about the “small progress” the community has made preserving Taokas over the past two decades, but she also worries about its future.

“Our population is small, and it’s not a language that can be used daily. The practical applications are very limited,” she says. “But we have to do what we can.”

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Lines between cop and criminal get murky in Joe Carnahan’s The Rip, a crime thriller set across one foggy Miami night, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Damon and Affleck, of course, are so closely associated with Boston — most recently they produced the 2024 heist movie The Instigators there — that a detour to South Florida puts them, a little awkwardly, in an entirely different movie landscape. This is Miami Vice territory or Elmore Leonard Land, not Southie or The Town. In The Rip, they play Miami narcotics officers who come upon a cartel stash house that Lt. Dane Dumars (Damon)

Today Taiwanese accept as legitimate government control of many aspects of land use. That legitimacy hides in plain sight the way the system of authoritarian land grabs that favored big firms in the developmentalist era has given way to a government land grab system that favors big developers in the modern democratic era. Articles 142 and 143 of the Republic of China (ROC) Constitution form the basis of that control. They incorporate the thinking of Sun Yat-sen (孫逸仙) in considering the problems of land in China. Article 143 states: “All land within the territory of the Republic of China shall