The Celebrity Solstice was given a civic reception when it docked in Newcastle in 2014. The lord mayor wore his robes and chains and personally welcomed passengers to the city; such was the pageantry required for a destination to impress the cruise industry in the hope of sharing in some of its spoils.

Thousands lined the waterfront in Darwin, Brisbane and Sydney to glimpse the Ovation of the Seas — the largest cruise liner to operate in Australia — when it first docked in those cities.

This month those same ships, along with about a dozen more, were ordered to leave Australian waters without ceremony.

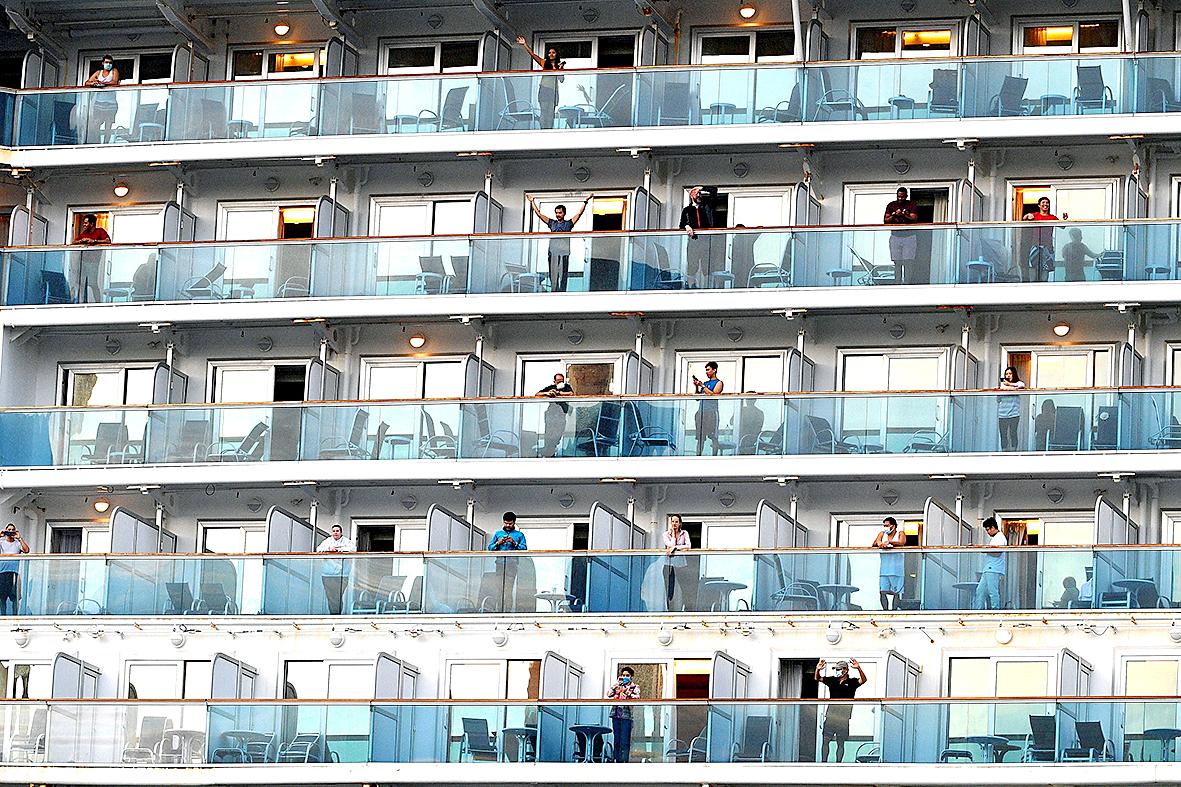

Photo: AFP

More than 700 passengers from one ship alone, the ill-fated Ruby Princess, have been infected with COVID-19, and at least 21 have died. Almost 200 crew members among the 1,000 who were still on board at Port Kembla on Tuesday have tested positive, and the ship’s final cruises are now the subject of a criminal investigation, at least one private lawsuit and a potential class action.

Both Celebrity Solstice and Ovation of the Seas have also been linked to coronavirus cases and at least one death each, and the banishment of these floating cities marks an unprecedented and sudden rebuke for an industry that has grown rapidly in size and influence during the past two decades.

More than 1.35 million Australians took an ocean cruise in 2018 — a tenfold increase since 2002. During that period, governments and local councils around the coastline have hatched plans to dredge waterways and construct passenger terminals to accommodate larger liners and more frequent visits. Many of those proposals are now in limbo, amid uncertainty about when — or if — the cruise industry will recover.

Photo: AFP

The industry has for several years been agitating for another Sydney terminal to allow for increased traffic during peak season and to cater for larger ships that cannot dock at existing berths in Sydney Harbor.

The New South Wales government had been considering two sites — at Yarra Bay and nearby Molineux Point on Botany Bay — and was understood to be on the verge of approving the project. The process has now been shelved for 18 months.

“We have got new people coming to the campaign every day now,” says Maria Poulos from the Save Yarra Bay Coalition, which opposes the proposal.

Photo: EPA-EFE

“I thought we would lose momentum after that announcement, but what’s happened is we’ve had an increase in membership. Obviously there’s been attention on the business practices of the cruise industry and the cosy relationships governments have with the cruise industry.”

Poulos says the coronavirus situation has highlighted the need for sustainable, environmentally-friendly tourism and argues the state should consider a cap on cruise ships in Sydney.

‘A BAD NEIGHBOR’

The remarkable growth in cruise tourism in Australia has occurred at the same time as several uncomfortable revelations about the cruise industry — onboard incidents such as the death of Dianne Brimble in 2002, virus outbreaks amplified by the confined quarters and concerns about pollution and environmental practices.

Attracting cruise visits has often been sold by proponents as an economic panacea that outweighs environmental and community concerns.

But those who live near terminals are often much less enthusiastic.

“The cruise industry has been a very bad neighbor for residents in White Bay and Balmain,” says Darcy Byrne, the mayor of Sydney’s Inner West council.

Residents of Balmain have long complained about pollution and noise from liners parked at White Bay since the area was opened as the city’s second cruise terminal in 2013. Because there is no shore-to-ship power at the berth, vessels sitting idle in the harbor are powered by bunker fuel. Regulations to lower bunker fuel emissions were first put in place in Sydney Harbor in 2015.

“The thing that’s always rankled is that we were told the reason we had to have a cruise ship terminal at White Bay was because the industry was going gangbusters and it was such a crucial part of our economy and our tourism sector,” Byrne said.

“If you’re going gangbusters you can surely afford some basic environmental protection so you don’t burn bunker fuel near people’s homes.”

Byrne said communities where terminals were proposed should “heed the lessons from Balmain.” They included the need for environmental protections and to ensure communities impacted by development then had some stake in the economic benefits.

“Don’t let the facility open there without proper environmental protections being in place in the first place,” Byrne says. “We all accept that tourism is vital and important and I’m personally very scared about the impact on our wider economy. But there’s been essentially zero economic benefit for the main street in Balmain and our local economy for having the passenger terminal there for the past five years. We basically didn’t get a single dollar of economic benefit out of it.”

‘DO WE EVEN WANT THEM?’

On the Gold Coast, the local council has developed an unconventional plan to attract the cruise industry to a region with no deepwater harbor. The city wants to build a 1.2km jetty from The Spit to allow ships to dock in the ocean and passengers to disembark on the glitter strip.

The Queensland tourism minister, Kate Jones, said last week that earmarked projects such as the Gold Coast terminal were likely to be delayed, but the local mayor, Tom Tate, has indicated his desire to proceed with the planning process.

Steve Gration, from the community group Save Our Spit, said the council’s feasibility studies had raised serious questions about the terminal’s viability and ability to attract investment, even before the coronavirus outbreak.

Gration said the coronavirus situation meant any planning would now need to be revised.

“If they weren’t coming before, how many [cruise ships] are going to come now, and do we want them? Do we even want them coming to a place that is predominantly tourism and education centered ... do we want our workforce to be decimated by these diseases on the small chance that passengers might spend a few dollars on a Surfers Paradise T-shirt? I don’t think the risk is warranted.

Gration said the order by the Queensland premier, Annastacia Palaszczuk, for cruise ships to leave the state was a signal that support for the industry was “at an all-time low.”

“I think there was a clear indication in that moment that the honeymoon period of cruise ships and Queensland, they’re not in the good books.”

A new cruise terminal at Luggage Point in Brisbane is due to open in October. The Port of Brisbane has said that, given the state has a temporary ban on cruising in place, it is “too early to understand” when the first ships will dock and how the facility will be affected in the long term.

‘PEOPLE WILL GET BACK OUT TO SEA’

Most in the cruise industry and other observers believe it is too early to properly understand how the sector will be changed, and how quickly it can recover, from the impact of the coronavirus crisis.

“Cruise travel, you would expect to be sitting right towards the end, if not the very last thing, that is reactivated again, given the difficulties Australia has faced with the cruise sector,” the tourism minister, Simon Birmingham, has said.

Remarkably, some reports suggest an increase in the number of cruise bookings for next year, as passengers use credits to reschedule voyages canceled due to the coronavirus crisis.

“Cruising has been embraced by so many Australians over the past 10 years and I believe that once it is safe for us to socially integrate and travel, people will get back out to sea,” says Jill Abel, the chief executive of the Australian Cruise Association, the industry’s cooperative marketing arm.

“The work that we have done with local and state governments developing access to regional ports around the country will definitely be an asset in getting Australian cruise passengers out to the regional areas that they may not have planned to visit prior to this. Cruise will therefore play a vital role in the recovery of local tourism in communities that have done it tough since Christmas.”

Abel says the industry hopes to resume discussions with governments about future infrastructure needs “when the timing is right in the future.”

The managing director of the Cruise Lines International Association, Joel Katz, says infrastructure planning should be a long-term process and take into account developments many years into the future. He says Clia member cruise lines introduced new screening protocols within 48 hours of the WHO declaring a public health emergency, and the cruise industry was the first to voluntarily suspend operations worldwide.

“Australians in particular have a passion for cruising, which is reflected in this region having the highest market participation rate of any major established cruise market in the world,” Katz says.

“The cruise industry is deeply connected to the Australian community and to the Australian economy, and we believe our industry has the resilience and responsibility to overcome the challenges ahead.

“Clia is now working with its members, medical experts and global health authorities on the changes our industry will need to make in our future operations in order to move forward and be successful in a world impacted by COVID-19.”

Jacques Poissant’s suffering stopped the day he asked his daughter if it would be “cowardly to ask to be helped to die.” The retired Canadian insurance adviser was 93, and “was wasting away” after a long battle with prostate cancer. “He no longer had any zest for life,” Josee Poissant said. Last year her mother made the same choice at 96 when she realized she would not be getting out of hospital. She died surrounded by her children and their partners listening to the music she loved. “She was at peace. She sang until she went to sleep.” Josee Poissant remembers it as a beautiful

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades

Lori Sepich smoked for years and sometimes skipped taking her blood pressure medicine. But she never thought she’d have a heart attack. The possibility “just wasn’t registering with me,” said the 64-year-old from Memphis, Tennessee, who suffered two of them 13 years apart. She’s far from alone. More than 60 million women in the US live with cardiovascular disease, which includes heart disease as well as stroke, heart failure and atrial fibrillation. And despite the myth that heart attacks mostly strike men, women are vulnerable too. Overall in the US, 1 in 5 women dies of cardiovascular disease each year, 37,000 of them

Politically charged thriller One Battle After Another won six prizes, including best picture, at the British Academy Film Awards on Sunday, building momentum ahead of Hollywood’s Academy Awards next month. Blues-steeped vampire epic Sinners and gothic horror story Frankenstein won three awards each, while Shakespearean family tragedy Hamnet won two including best British film. One Battle After Another, Paul Thomas Anderson’s explosive film about a group of revolutionaries in chaotic conflict with the state, won awards for directing, adapted screenplay, cinematography and editing, as well as for Sean Penn’s supporting performance as an obsessed military officer. “This is very overwhelming and wonderful,” Anderson