There was, as there often is in Taiwan’s countryside, the rumble and screech of a distant karaoke. But once the singing session had finished and the sound had died away, it was blissfully quiet. In Taiwan, silence is an even more precious commodity than proximity to nature.

Sheltering from the sun under a viewing platform atop Yunlin County’s Hushan Main Dam (湖山主壩), I turned away from the reservoir just in time to see a Crested serpent eagle rise above the barrage. It hovered for a few moments, then dived out of sight. I don’t think I scared it away. It hadn’t even glanced in my direction. Most likely, it’d spotted a rodent or a tasty-looking lizard.

This was my third visit to this corner of Yunlin County, but the first since 2007. Back then, I’d visited at the behest of environmentalists opposed to the dam project. Some of them were concerned that, by increasing the region’s supply of water, the reservoir would make possible even greater industrialization along the coast. Others were birding enthusiasts who feared for the future of the Fairy pitta, a spectacular but (according to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species) vulnerable avian.

Photo: Steven Crook

The Chinese name of the Fairy pitta (八色鳥) translates as “eight-color bird” It has white, green, yellow, and red plumage on its underside; two shades of blue on its wings; plus black and brown on its head. It’s somewhat larger than the Eurasian tree sparrows common throughout Taiwan.

The Fairy Pitta is far from numerous — estimates for the total global population range from 1,500 to 7,000 — yet it’s found in several parts of East and Southeast Asia. Much of what has been described as the species’ “most important breeding site” now lies underwater, or was seriously impacted by the construction of the three conjoined dams at Hushan. According to figures published on the Web site of Taiwan’s Public Television Service Foundation, the number of Fairy Pittas in the area fell from 150 to 160 before ground was broken to fewer than 60 in 2011.

I’ve not been able to find more recent data, even though in late 2008 the government established the 1,737-hectare Yunlin Huben Fairy Pitta Major Wildlife Habitat (雲林湖本八色鳥野生動物重要棲息環境) to preserve the bird’s habitat and related forest ecosystems. Naturalists were further dismayed that the project would inundate Youcinggu (幽情谷), a narrow ravine home to rare plants and 21 of Taiwan’s 37 amphibian species.

Photo: Steven Crook

Other opponents worried that the dams (total length 1,621m) could collapse during an earthquake, sending a wall of water through the communities that lie downstream. I asked the contractor about this, and was told that a key feature is a cut-off wall whose characteristics, among them density, are deliberately similar to the surrounding soil and geology. Therefore, if there’s a serious tremor, the cut-off wall will “resonate” (shake) with the ground, reducing the risk of cracking and water leakage.

In April 2016, the dam’s sluice gate was closed and the reservoir began to fill up. The body of water thus created has a surface area of just over 2km square. However, earthworks are ongoing, because the authorities determined that a second intake-outlet will reduce expenditure on silt removal.

When I arrived at Hushan Reservoir Management Center (湖山水庫管理中心), having pedaled up the hill from Douliu (斗六), a security guard told me I couldn’t take my bike any further. The roads immediately north and south of the reservoir that I’d seen on satellite photos were off limits to all outside vehicles. I had no choice but to join the joggers and senior couples strolling along the top of the barrage and taking in the view over Douliu.

Photo: Steven Crook

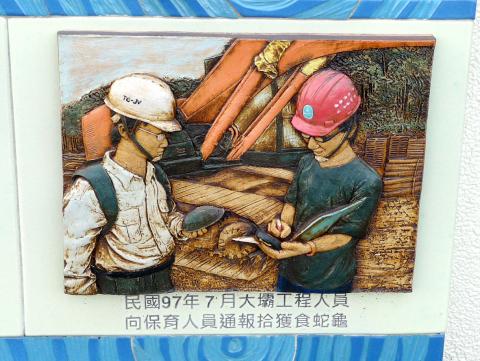

The management center is at the southern end of the dam, and near it dozens of colorful ceramic relief images decorate the walls. Each picture is accompanied by a short piece of text in Chinese. Some describe the equipment used to construct the dam, while others focus on local history and ecology. Among the creatures depicted are the Crab-eating mongoose and the Yellow-margined box turtle; both species are protected in Taiwan.

Most people stay close to the management center. Before I’d reached the midway point, I was enjoying complete solitude. After the encounter with the eagle, I walked to the northern end of the barrage, but not beyond. A sign told me not to go any further, and the road was surveilled by CCTV.

Looking from that spot down over the front of the dam, I noticed an array of more than 1,000 photovoltaic panels. It was an encouraging yet also mystifying sight: Visible evidence of the progress Taiwan is making when it comes to renewable energy — but there was enough empty flat land around this solar power station to add several hundred more panels.

Photo: Steven Crook

I returned to my bike and freewheeled down to the tiny village at the base of the dam. Called Changzihkeng (檨子坑), it’s home to a local god with a backstory unlike any other deity.

As far as I’ve been able to find out, the General Who Protects Changzihkeng (保坑大將軍), began his existence as a statue decorating a restaurant-nightclub in Taipei in 1996. Within months, the business had closed down because police raids had found minors inside. When the owner returned to his native Yunlin, he took the statue with him.

Some say the rifle-toting statue — which you can’t miss if you go into the village — depicts an Indian soldier. To my eyes, he looks more like a man from a Mediterranean country in a uniform similar to those worn by Confederate troops in the US Civil War.

Photo: Steven Crook

The cult seems to have started after the owner’s parents fell ill. They prayed to the general and credited their recovery to him. One account mentions a Singaporean conscript who died while training in the area, but my language skills and cultural knowledge are insufficient to grasp the connection. I’m intrigued by these vague story-threads, yet unsurprised. When I travel around Taiwan, I often go home with more questions than answers.

Steven Crook has been writing about travel, culture, and business in Taiwan since 1996. He is the co-author of A Culinary History of Taipei: Beyond Pork and Ponlai, and author of Taiwan: The Bradt Travel Guide, the third edition of which has just been published.

One of the biggest sore spots in Taiwan’s historical friendship with the US came in 1979 when US president Jimmy Carter broke off formal diplomatic relations with Taiwan’s Republic of China (ROC) government so that the US could establish relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Taiwan’s derecognition came purely at China’s insistence, and the US took the deal. Retired American diplomat John Tkacik, who for almost decade surrounding that schism, from 1974 to 1982, worked in embassies in Taipei and Beijing and at the Taiwan Desk in Washington DC, recently argued in the Taipei Times that “President Carter’s derecognition

This year will go down in the history books. Taiwan faces enormous turmoil and uncertainty in the coming months. Which political parties are in a good position to handle big changes? All of the main parties are beset with challenges. Taking stock, this column examined the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) (“Huang Kuo-chang’s choking the life out of the TPP,” May 28, page 12), the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) (“Challenges amid choppy waters for the DPP,” June 14, page 12) and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) (“KMT struggles to seize opportunities as ‘interesting times’ loom,” June 20, page 11). Times like these can

June 23 to June 29 After capturing the walled city of Hsinchu on June 22, 1895, the Japanese hoped to quickly push south and seize control of Taiwan’s entire west coast — but their advance was stalled for more than a month. Not only did local Hakka fighters continue to cause them headaches, resistance forces even attempted to retake the city three times. “We had planned to occupy Anping (Tainan) and Takao (Kaohsiung) as soon as possible, but ever since we took Hsinchu, nearby bandits proclaiming to be ‘righteous people’ (義民) have been destroying train tracks and electrical cables, and gathering in villages

Dr. Y. Tony Yang, Associate Dean of Health Policy and Population Science at George Washington University, argued last week in a piece for the Taipei Times about former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) leading a student delegation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that, “The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world” (“Ma’s Visit, DPP’s Blind Spot,” June 18, page 8). Yang contends that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has a blind spot: “By treating any