When a 35-year-old Japanese man married a hologram of teenage virtual idol singer Hastune Miku in November last year, the news felt to me like a turning point for humanity. Beautiful girls have always been objects of desire, but we’re now in an age when technology and social alienation can together stoke the flames of fantasy into something never seen before.

In Bishojo: Young Pretty Girls in Art History, a new exhibition at the Museum of National Taipei University of Education (MoNTUE), that modern fantasy is given historic context. Two-hundred years of Japanese visual culture reveal the dynamic roles that bishojo (literally “pretty young girls”) have played as consumers and products, as symbols of tradition and progress, as objects for others’ aesthetic pleasure and subjects with their own psychological complexity.

That’s serious food for thought, but MoNTUE is likely also banking on Bishojo’s content being approachable enough to attract an audience outside of the usual museum-going milieu. Visiting in the opening week, I spotted several groups of unchaperoned teenage girls, as well as two bright-eyed elementary school boys with their mother. “So cute!” cooed two 30-something-year-old women as they left the exhibition.

Photo courtesy of Museum of National Taipei University of Education

GIRLS’ GENERATION

Men and women alike will pay to see a pretty girl, so Bishojo turns out to be as much about consumerism as it is about art history. The line between high and low culture is ripe for breaching with this subject matter, and curator Takeshi Kudo of the Aomori Museum of Art exploits that for entertainment and scholarship.

Several artworks are a nod to the massive industry around shojo manga, or comics aimed at young girls — think Sailor Moon and Cardcaptor Sakura. Others comment on lolicon (“Lolita complex”) culture, which services sexual attraction to prepubescent girls. And lest you think these are exclusively modern-day perversions, the number of Edo-era woodblock prints of beautiful women in bijinga (literally “pretty person picture”) genre will put that notion to rest.

Photo courtesy of Museum of National Taipei University of Education

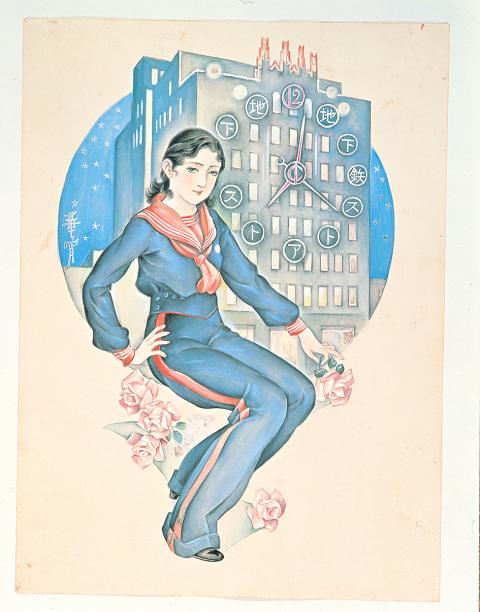

The connection between girlhood and consumerism is most evident in a remarkable archive of early 20th-century commercial illustrations from shojo magazines assembled in the basement of the museum, which is also the recommended starting point for the exhibition.

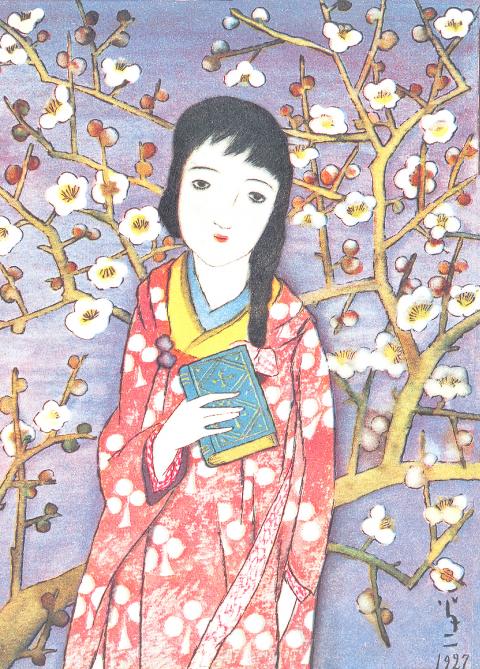

Riding a wave of shojo culture that peaked in the 1930s, artists like Yumeji Takehisa and Kasho Takabatake created portraits of attractive young women who exude glamor, sophistication and adventure, but also innocence, friendship and domestic virtue in turn. Even now, there’s a lot to admire in their rich colors and finely-drawn features, many of which exhibit Western markers of beauty such as fair hair.

In the wake of Hannah Montana, there’s been a lot of hand-wringing about the growing commercialization of tween girls (aged between 9 and 12) in contemporary society. But curatorial notes make it clear that even in pre-World War II Japan, girls saw the women in shojo magazines as aspirational figures and followed them for the latest fashions. As it turns out, tweens have long had purchasing power.

Photo courtesy of Museum of National Taipei University of Education

INNER WORLDS

This awareness of young girls as a distinct social and consumer class forms the basis for approaching the other five sections in the exhibition, each of which examines a particular representation of girls in visual culture. For example, character designs for Hatsune Miku — the aforementioned virtual idol singer designed never to age beyond 16 years — turn up in a section on feminine divinity and mysticism, in a nod to her potency as a modern-day priestess with a devoted following.

What’s crucial is that every section is charged with questions of agency and the power dynamic between artist, viewer and object of each artwork — invariably a girl. This conflict is ultimately what powers Bishojo as a whole.

A section titled Into the Minds of Young Girls delves most directly into the inner worlds of our young female protagonists. Yoshitoshi Kanemaki’s hand-carved wooden sculptures with multiple faces have been described as glitch-like, but could also resemble four-faced Buddhas. His figures in Congratulations Caprice and Wheel Calmato 2nd portray the ambiguous emotions and mental states of a bride and young girl respectively.

Hisaji Hara applies a distinctly Japanese sense of eroticism to black-and-white photographic reenactments of paintings by the Polish-French artist Balthus (whose second wife was Japanese). Subtly altering hemlines and gazes, he creates a brand of psychological intrigue utterly unlike that of the original works. The girls may be in school uniforms, but so are the boys, and it’s not entirely clear who’s in control.

In recent years, Yoshitomo Nara’s paintings of young girls with short hair and piercing eyes have been reduced to decorations on the covers of notebooks available at any Eslite stationery section. Here, they regain some conceptual integrity as his caustic, vulgar and violent characters are a gleeful counterpoint to the immaculate female figures in the basement — and just as commercially successful.

The exhibition also contains guidance on how to view more voyeuristic artworks, which describes many of the early ukiyoe or woodblock prints, with a critical eye. Curatorial notes refer to art historian Wakakuwa Midori’s observation that the point of an artwork depicting a courtesan or female nude is the “subtle momentum produced in her physicality when a woman is drawn by something” and “one-sidedly bearing the viewer’s gaze.”

There is no doubt an effort to delve into complex portrayals of girlhood in Bishojo. Yet however well-rounded these depictions are, what nags at me as I make my way through the exhibition is the absence of more female creators.

That makes Shoen Uemura, one of Japan’s most important artists who remained prominent throughout the mid-19th to mid-20th centuries, a welcome inclusion. Sei Shonagon, painted in the nihonga style following traditional Japanese artistic conventions, depicts an accomplished author and court lady who lived in the 11th century. Another notable female artist is Yuko Fukase, whose young girl with a bob and an unwavering stare in ALICE provides a direct challenge to viewers’ gazes.

There are inconclusive arguments around the extent to which an artist’s identity actually matters in our appreciation of the artwork. But when gender is the focus, it’s hard not to wonder how a gender imbalance in the artists’ line-up affects the range of viewpoints presented. Art may not have been a realistic livelihood for most women in pre-modern Japan — that’s why Uemura was exceptional, among her other merits — but the fact that female contemporary artists also remain poorly represented is harder to understand.

These are important omissions, but they ultimately do not constitute a critical failure for Bishojo which remains a thought-provoking and entertaining excavation of a form of visual culture that many of us take for granted.

One of the biggest sore spots in Taiwan’s historical friendship with the US came in 1979 when US president Jimmy Carter broke off formal diplomatic relations with Taiwan’s Republic of China (ROC) government so that the US could establish relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Taiwan’s derecognition came purely at China’s insistence, and the US took the deal. Retired American diplomat John Tkacik, who for almost decade surrounding that schism, from 1974 to 1982, worked in embassies in Taipei and Beijing and at the Taiwan Desk in Washington DC, recently argued in the Taipei Times that “President Carter’s derecognition

This year will go down in the history books. Taiwan faces enormous turmoil and uncertainty in the coming months. Which political parties are in a good position to handle big changes? All of the main parties are beset with challenges. Taking stock, this column examined the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) (“Huang Kuo-chang’s choking the life out of the TPP,” May 28, page 12), the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) (“Challenges amid choppy waters for the DPP,” June 14, page 12) and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) (“KMT struggles to seize opportunities as ‘interesting times’ loom,” June 20, page 11). Times like these can

JUNE 30 to JULY 6 After being routed by the Japanese in the bloody battle of Baguashan (八卦山), Hsu Hsiang (徐驤) and a handful of surviving Hakka fighters sped toward Tainan. There, he would meet with Liu Yung-fu (劉永福), leader of the Black Flag Army who had assumed control of the resisting Republic of Formosa after its president and vice-president fled to China. Hsu, who had been fighting non-stop for over two months from Taoyuan to Changhua, was reportedly injured and exhausted. As the story goes, Liu advised that Hsu take shelter in China to recover and regroup, but Hsu steadfastly

You can tell a lot about a generation from the contents of their cool box: nowadays the barbecue ice bucket is likely to be filled with hard seltzers, non-alcoholic beers and fluorescent BuzzBallz — a particular favorite among Gen Z. Two decades ago, it was WKD, Bacardi Breezers and the odd Smirnoff Ice bobbing in a puddle of melted ice. And while nostalgia may have brought back some alcopops, the new wave of ready-to-drink (RTD) options look and taste noticeably different. It is not just the drinks that have changed, but drinking habits too, driven in part by more health-conscious consumers and