July 8 to July 14

By the time US aid to Taiwan officially terminated in July 1965, the Americans had provided about US$1.4 billion in economic assistance over 15 years, supporting a large number of vital industries — including power, transportation, construction and telecommunications. It also covered various education projects and professional training.

But one seldom-discussed aspect of US aid in Taiwan is its influence on the local literary scene, which was apparently strong enough to spawn several academic studies on the topic.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The late Richard McCarthy, who ran the US Information Services (USIS) between 1958 and 1962, said in a Library of Congress interview: “I think the most notable thing about the time I was [in Taiwan] was the work that we did with young writers and artists.”

Under McCarthy, the USIS sponsored and translated a significant number of works by young Taiwanese writers, and also published books featuring local avant-garde artists.

McCarthy said that a reason for doing so was to compete with the “outpouring of works” from Beijing’s Foreign Languages Press. Like their Chinese counterparts, the USIS-sponsored works were “designed for distribution to the rest of the world.”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

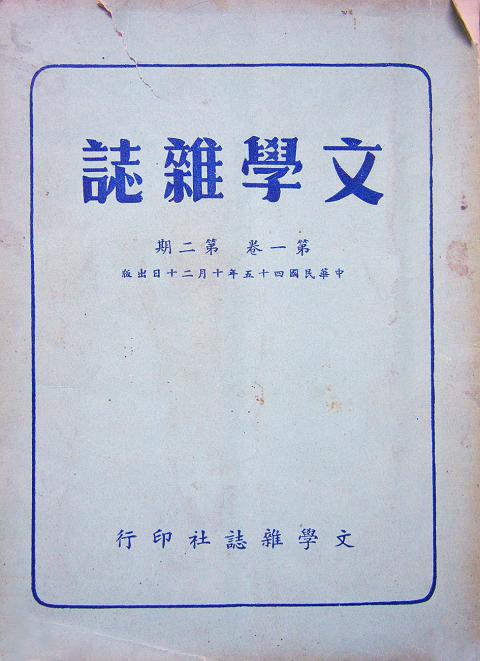

The USIS also sponsored the magazines Literary Review (文學雜誌) and Modern Literature (現代文學) to provide an outlet for young modernist writers.

Tsai Shih-jen (蔡世仁) writes in Study on the Influence of US Aid Literary Institutions on Taiwan’s Literature Field in the 1960s (1960年代美援文藝體制與台灣文壇關係研究): “While the government sought to foster an anti-communist literary scene in the 1960s, [McCarthy] took further action and worked closely with Taiwanese writers.”

TRANSLATION SERVICES

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

McCarthy majored in American literature in college and was also fluent in Mandarin, having first served as vice-consul in China in 1947.

In Taiwan, McCarthy worked closely with Lucian Wu (吳魯芹), who worked at USIS and taught at National Taiwan University’s Department of Foreign Languages. Wu essentially served as McCarthy’s adviser on Taiwanese literature, Tsai writes.

Due to the still-developing economy and authoritarian rule, it was almost impossible to privately translate and publish Taiwanese works in English; nor was it easy to run a literary magazine. But the USIS had the resources and personnel to complete such tasks.

Photo courtesy of National Museum of Taiwan Literature

“Taiwan in the 1960s did not have the means to produce and market foreign-language translations of local literature,” Tsai writes. “But under the Cultural Cold War, the US government under the backing of US Aid published Taiwanese works for foreign audiences. This was a very precious opportunity for Taiwan … but it’s also proof of US intervention in Taiwan’s literary scene.”

Shortly after McCarthy’s arrival, he set up Heritage Press, which translated and published eight modern Taiwanese novels and anthologies during the 1960s.

The first was New Chinese Poetry, edited and translated by noted poet and essayist Yu Kuang-chung (余光中). Other notable names include Nieh Hua-ling (聶華苓), who translated her own anthology, and Chen Jo-hsi (陳若曦), whose Spirit Calling: Five Stories of Taiwan (招魂) was published just a year after she graduated from college.

“Although McCarthy’s goal was to compete with Beijing — in other words, combat communism — it was the first time anyone systematically launched Taiwan’s modern works into the international literary scene,” Tsai writes.

SPONSORING LITERATURE

In 1956, Wu and several other writers founded Literary Review, which featured up-and-coming talent such as Kenneth Pai (白先勇) and the aforementioned Nieh and Chen. The magazine struggled financially until Wu convinced McCarthy to sponsor it, writes Yu in a 1983 China Times (中國時報) article.

However, Wang Mei-hsiang (王梅香) writes in the study ‘Literary Review’ and ‘Modern Literature’ Under the US Aid Literary Institution (美援文藝體制下的《文學雜誌》與《現代文學》) that Literary Review was founded under American influence from the beginning. The evidence lies in McCarthy’s annual report for 1960, where he notes that the magazine was founded by a local publisher “at our suggestion.”

“The magazine was designed originally to recruit Chinese writers from all over the world to show that Free China is the center of the Chinese literary scene,” McCarthy adds.

Wang writes that this was part of a larger effort to attract ethnic Chinese in Southeast Asia to continue their studies in Taiwan instead of China.

“The consensus seemed to favor USIS Taipei’s support for the magazine, for all responding posts agreed that Literary Review is valuable as a medium to reach the overseas Chinese elite,” a USIS survey on the publication states.

The survey also notes that the magazine would provide an alternative to leftist publications, noting that communists in Malaysia, for example, “frequently exploited [literature] for their own ends.”

After Literary Review folded in 1960, Modern Literature carried on the mantle with US support. Although these magazines had ulterior motives, they did influence the development of Taiwan’s literary scene at the time, providing opportunities for many young writers whose names are still known today.

“To USIS, the political, educational and propaganda qualities of these two magazines were far more important than their literary nature,” Wang writes. “Taiwan’s post-war British-American modernist literature scene was actually born from US cultural propaganda. While the Americans were thinking of politics, Taiwan’s intellectuals pursued literature. They worked together under different motives.”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

The Taipei Times last week reported that the rising share of seniors in the population is reshaping the nation’s housing markets. According to data from the Ministry of the Interior, about 850,000 residences were occupied by elderly people in the first quarter, including 655,000 that housed only one resident. H&B Realty chief researcher Jessica Hsu (徐佳馨), quoted in the article, said that there is rising demand for elderly-friendly housing, including units with elevators, barrier-free layouts and proximity to healthcare services. Hsu and others cited in the article highlighted the changing family residential dynamics, as children no longer live with parents,

Oct 20 to Oct 26 After a day of fighting, the Japanese Army’s Second Division was resting when a curious delegation of two Scotsmen and 19 Taiwanese approached their camp. It was Oct. 20, 1895, and the troops had reached Taiye Village (太爺庄) in today’s Hunei District (湖內), Kaohsiung, just 10km away from their final target of Tainan. Led by Presbyterian missionaries Thomas Barclay and Duncan Ferguson, the group informed the Japanese that resistance leader Liu Yung-fu (劉永福) had fled to China the previous night, leaving his Black Flag Army fighters behind and the city in chaos. On behalf of the

I was 10 when I read an article in the local paper about the Air Guitar World Championships, which take place every year in my home town of Oulu, Finland. My parents had helped out at the very first contest back in 1996 — my mum gave out fliers, my dad sorted the music. Since then, national championships have been held all across the world, with the winners assembling in Oulu every summer. At the time, I asked my parents if I could compete. At first they were hesitant; the event was in a bar, and there would be a lot

Smart speakers are a great parenting crutch, whether it be for setting a timer (kids seem to be weirdly obedient to them) or asking Alexa for homework help when the kids put you on the spot. But reader Katie Matthews has hacked the parenting matrix. “I used to have to nag repeatedly to get the kids out of the house,” she says. “Now our Google speaker announces a five-minute warning before we need to leave. They know they have to do their last bits of faffing when they hear that warning. Then the speaker announces, ‘Shoes on, let’s go!’ when