Patrick Lee (李紹榮) doesn’t know what blockchain is. The 71-year-old artist knows what it can do, however, and is eager to be at the forefront, or rather a guinea pig, for the fast-evolving technology that only extended its reach into the art world last year.

“It’s a new marketing channel,” Lee says. “I know it divides my work into many shares so more people, or people who couldn’t afford it before, can own part of it.”

If Lee is a guinea pig, it helps that he has an experimenter he fully trusts — his friend Lai Chih-hsing (來智行) is CEO of TokenBacon, a Taiwanese startup that says it has developed the world’s first blockchain interface that allows anyone to instantly and affordably tokenize their property, either physical or intellectual, instead of having to rely on blockchain experts.

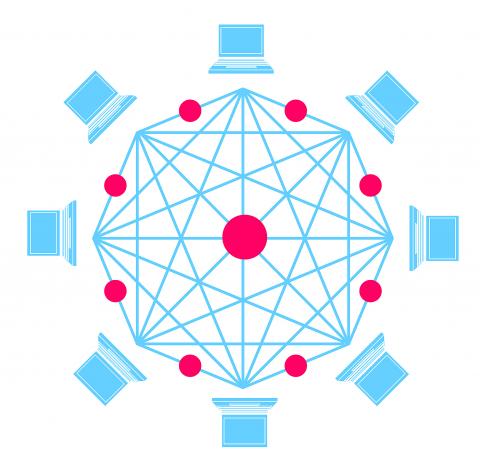

Photo courtesy of Pixabay

Blockchain is, simply put, a time-stamped digital record of data that is managed across a cluster of computers instead of being centralized in one entity. All records of past modifications and transactions are transparent, thus one cannot change the information without leaving a trace.

There’s nothing more important in the art market than authenticity and intellectual property rights, and keeping such a record serves as a digital certificate that can always be traced back to the creator or collector who blockchained the artwork. If the artwork is fake, the unfortunate buyer can trace it back to the person who originally created the certificate. Lai says that anything can be tokenized with TokenBacon’s technology.

“Even your girlfriend’s photo,” Lai says, though it’s up to the market to determine if it has any value.

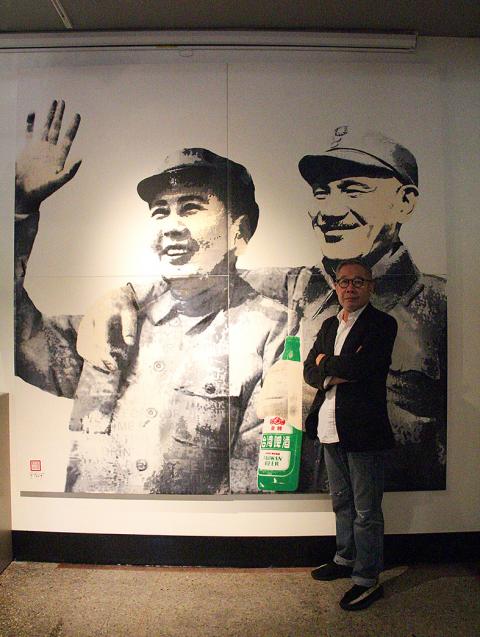

Photo courtesy of TokenBacon

Lee’s iconic print A Time to Drink, which shows longtime adversaries Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) and Mao Zedong (毛澤東) drinking Taiwan Beer, has been divided into 396,000 digital tokens worth US$1 each, with every token carrying the blockchained information of authenticity. This not only makes Lee’s art more affordable, as someone can buy a fraction of the painting in token form, but also prevents his work from being copied or altered as any changes will be reflected in the blockchain.

BLOCKCHAIN AND THE ART INDUSTRY

Lai says that while people saw the possible uses for blockchain when it first appeared, its uses were mostly limited to digital currency and smart contracts since the technology was so new. Even last year, he says, TokenBacon would not have been able to create their product as it would take too much time and money to tokenize just one piece of property.

Last September, about 30 percent of Andy Warhol’s 14 Small Electric Chairs became the world’s first artwork to be tokenized and sold on blockchain. Lai says that such feats have been mostly one-off projects due to the time and cost to accomplish the feat. Furthermore, they say their technology is the first to be able to easily take the blockchain information and manifest it as a small photo of Lee’s painting, serving as a concrete “certificate” of authenticity for the artwork.

“Before, if you wanted to divide a painting into many shares, you had to find a lawyer to notarize each portion before distributing it,” TokenBacon regional manager Sunny Lin (林善理) says.

Hannah Liu (劉家榮), a spokesperson for Art Emperor (帝圖), which runs online galleries, art sales as well as online and offline auctions, says that most auctioned pieces are extremely high-priced works that have stood the test of time — meaning that the creator is unlikely to be alive. These works have gone through many hands, requiring expert authentication. In this case, it’s impossible to achieve blockchain’s purported ethos of decentralization since a central authority is still needed.

Liu says blockchain is promising, but there are still many kinks that need to be ironed out for traditional dealers to embrace it. For example, much of the information on pricing, profits and collectors remains top secret among dealers. Rival auction houses, for example, will not be willing to share their information with each other, making transparency difficult. Just a photo online is not enough to convince people to buy, as it might not be exactly the same in tone as the original. In addition, paintings will deteriorate — especially Chinese ink paintings, and someone would need to reflect those changes in the blockchain.

TokenBacon acknowledges that blockchain cannot solve these issues, instead envisioning a new ecosystem developing where they just provide the technology, with another company providing secure storage, and another in charge of authentication or marketing, for example. This can streamline and make transparent the selling process while proving authenticity, and all subsequent transactions will be recorded.

Liu says that the technology will benefit contemporary artists such as Lee or those who make digital art, since they are still creating new works that don’t have such obscured pasts.

Huang Chi-wen (黃其玟), whose Chi-Wen Gallery focuses on new media artists, is excited about blockchain’s possibilities and is watching its development closely.

“People were unsure of Web sites when they first came out, but now it’s a necessary tool for every business,” she says. “I see blockchaining becoming just as essential in the future.”

For example, if someone wants to own a video, they buy the file and the rights to play it in public. The gallery gives them a certificate of authentication, but the work is still a copy of the original. If the video is blockchained, however, not only does it prevent unauthorized copies, each copy becomes a unique piece with the certificate built in.

“It can even add value to the piece since the collector is buying the new technology as well,” Huang says.

Huang says it will take time for the technology to mature and to educate their collectors and artists about it. Today, art galleries still serve as authorities of quality and value, even though the Internet has enabled anyone to be a creator. Even if anyone can blockchain their creations and sell them, Huang does not see the role of the gallery fading.

ART AS INVESTMENT

The New York Times reported on the rise of using art as loan collateral in 2016, and while baby boomers are still the major players in the scene, the same year an American Attitudes Toward Art survey showed that 41.9 percent of millenials regard art buying as a good investment. They don’t need to have the painting; just owning a share of it is a good investment since its monetary value is less likely to depreciate.

Lee doesn’t mind if people treat art like stocks — he sees it as a way to get more young people interested in art. If you own part of something, you’ll likely do some research and learn to appreciate what you own, he says.

TokenBacon is pondering different ways to provide extra value to shareholders, for example owners of a certain share of Chang Ta-chien’s (張大千) Bird Among Red Leaves (紅葉小鳥), which the company has tokenized, can receive a professionally replicated print of the iconic painting. Another way is to give them free tickets to art shows or events. Lee, however, doesn’t want to speculate too much.

“This technology is still in its infancy and experimental stages, and I want to just let it develop freely. Nobody knows what shape it’s going to take in the end,” he says. “Don’t think. Just do it.”

Collectors who want to keep expanding their collection can also benefit from the technology, Lai says, by selling percentages of their existing collections to buy new art.

“People’s desires are bottomless,” he says. “They don’t want to outright sell their old paintings because they have sentimental value. So they put a few up on blockchain, and from the earnings, invest in a new painting, which could increase in value and make them even more money.”

Lee believes that tokenized artwork should be transferred to a third party for keeping, although those who own a share can request to view it. Lai sees it as the beginning of a “token economy,” where people are happy to own percentages of things without actually having them. It’s like investing in stocks — there’s no way an someone can come to own the entire TSMC corporation, Lai says, but people still buy shares of it.

“Now you can just focus on your investment without worrying about how to preserve the art,” Lai says.

BENEFITTING OTHER CREATORS

As a former music industry executive, Lai says a big problem was that a song’s creators — the musicians, the composer, arranger and so on, wouldn’t be paid if, for example, the record company decided to sign a contract with a major KTV chain to use their songs.

Blockchain can be applied to any intellectual property, including the news industry. By blockchaining and tokenizing an article, it prevents it from being copied or modified without attribution. It could even be set so that platforms would need to pay a tiny amount just to cite the information, solving the problem of losing one’s intellectual property in the Internet free-for-all.

This also protects all the creators of one article — the photographer, the editor, the writer may all be able to get a portion of the proceeds each time the article is shared or cited instead of the company reaping all the benefits. It also eliminates the issue of employees making the same salary despite the difference in quality of their work.

“Say I wrote a song 10 years ago. If I blockchained it, then every time someone listens to it, sings it or plays it in public, I make money. There’s no getting around it,” Lai says. “Even if I make NT$0.01 from each use, it adds up. We are returning the right to information back to the individual.”

Of course, there are risks with every new technology, and Lai says blockchain is no different; the danger lies in what humans choose to use it for.

“Blockchain solves a lot of problems, but never underestimate swindlers,” Lai says. “We don’t know what’s going to happen. We just provide a platform, and the rest of it is up to the user. But a government cannot block all the roads just to prevent car accidents.”

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) invaded Vietnam in 1979, following a year of increasingly tense relations between the two states. Beijing viewed Vietnam’s close relations with Soviet Russia as a threat. One of the pretexts it used was the alleged mistreatment of the ethnic Chinese in Vietnam. Tension between the ethnic Chinese and governments in Vietnam had been ongoing for decades. The French used to play off the Vietnamese against the Chinese as a divide-and-rule strategy. The Saigon government in 1956 compelled all Vietnam-born Chinese to adopt Vietnamese citizenship. It also banned them from 11 trades they had previously

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

As devices from toys to cars get smarter, gadget makers are grappling with a shortage of memory needed for them to work. Dwindling supplies and soaring costs of Dynamic Random Access Memory (DRAM) that provides space for computers, smartphones and game consoles to run applications or multitask was a hot topic behind the scenes at the annual gadget extravaganza in Las Vegas. Once cheap and plentiful, DRAM — along with memory chips to simply store data — are in short supply because of the demand spikes from AI in everything from data centers to wearable devices. Samsung Electronics last week put out word