Chen Hsin-yao (陳芯瑤) says the time has come for disabled artists to refuse pity as a default response to disability.

“Disability is an aid, not an impediment,” the ceramicist, 32, tells the Taipei Times.

At nine months, Chen was diagnosed with retinoblastoma, a rare form of eye cancer. After numerous surgeries and relapses, doctors removed her left eye when she turned five. She made a full recovery, graduated from the National Taiwan University of Arts’ Department of Crafts and Design and now maintains a studio in Taipei.

Photo: Davina Tham, Taipei Times

Chen makes brightly-colored functional pottery pieces that she decorates with animal motifs. Her dishes depict mischievous monkeys, languid cats and families of hens and chicks are hand-formed and hand-painted. She also makes kaleidoscopic hand-dyed textiles.

Chen credits her grueling childhood illness with helping her to put subsequent life challenges in perspective.

“When you have already encountered such a huge challenge in your life, what other problems can there be that you do not dare to face?” she says.

Photo courtesy of Chen Hsin-yao

For artist, activist and scholar Sandie Yi (易君珊), her disability directly inspires her creations.

“I make art not despite having a disability, [but] because of disability,” Yi says.

Yi, 37, was born with two fingers on each hand and two toes on each foot. She makes body adornments that reimagine medical prosthetic devices, which traditionally seek to correct the body’s form and function. Yi’s adornments express self-defined notions of beauty and accentuate distinctive features of the disabled body.

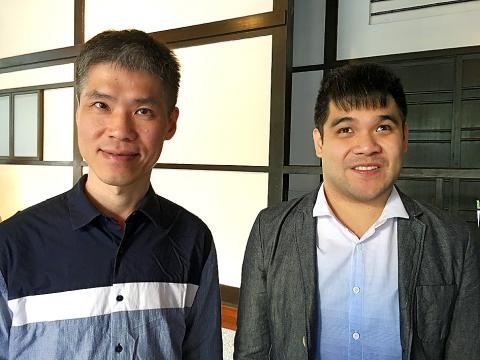

Photo: Davina Tham, Taipei Times

Past artworks include a pair of knit gloves customized for her hands and shoes that embellish, rather than hide, the shape of her feet with stones or horn-like protuberances rising from between her toes.

Yi, who is pursuing a doctorate in disability studies at the University of Illinois at Chicago, only started identifying as a “disabled person” when she was 25. This might sound unusual since she has been living with a congenital condition. But Yi is drawing on the progressive and increasingly accepted social model of disability, which posits that disability is a socialized condition resulting from an interaction between an individual and the environment.

Put plainly, people with impairments are only disabled insofar as they face discriminatory attitudes and systemic barriers in society.

Photo: Kuo Cheng-chang

DISABILITY CULTURE

Yi, who was born in Taiwan and schooled in the US from age 15, grew into this awareness after encountering disability culture in the US.

Yi says that her disability isn’t so much a medical problem as it is a problem that resides in social attitudes.

Photo: Louisa de Cossy

Chen’s experiences with the healthcare system in Taiwan demonstrate another way in which disability is socially constructed.

According to the government’s classification of disabilities, having only one eye is not considered a visual impairment, despite the condition significantly reducing Chen’s field of vision and affecting her sense of balance.

“When I was much younger, my father once tried to help me apply for disability status,” Chen says. “I think at the time, people did not have as much empathy. The social worker actually told my father, ‘Wait until her other eye loses vision and then come and apply again.’”

Photo: Kuo Cheng-chang

Chen finally received her disability status in university, after realizing that she could work around the bureaucratese if she classified her disability as a facial injury resulting from the loss of one eye, rather than a visual impairment.

AUDIENCE EXPECTATIONS

After a lifetime of confronting callous and ignorant attitudes, Chen and Yi exude confidence when discussing their disabilities. As artists, this also extends to the way that they want their work to be received.

“I am totally not interested in how to teach or how to ask non-disabled people to understand disabled bodies, because I feel like it’s too much emotional labor on us to... always have to convince the non-disabled people,” Yi says.

Yi considers her disability to be a “very important experience” that cannot be extricated from her identity.

“For me, I make art about my body as a political statement. It’s not about trying to convince people that, yeah, we are beautiful, we are functional or we can do just as well as you non-disabled people... I’m not interested in doing that. I am interested in using my disability as an aesthetic element,” she says.

But Yi acknowledges that disability is performed in different ways.

She points to the “overcoming narrative” as a trope commonly used by disabled artists in Taiwan. In this narrative, a performer’s impairment is highlighted so that they can be shown overcoming that impairment to produce a work of art.

For example, a deaf singer wearing a hearing aid belts out a popular tune, or a musician with no hands nevertheless dexterously manipulates a piano.

A flag-bearer of such performances is the Mixed Disabled Performing Arts Troupe (混障綜藝團). Its continued popularity can be attributed to the fact that the feel-good performances deliver inspiration and a satisfying emotional pay-off for audiences.

Through her own experiences, Chen has also come to see a dichotomy in the way artists feature their disability in their art. The first type, she says, prefers to play the sympathy card and constantly emphasize how difficult it was to create a work when they are trying to sell it.

“The second type is more like myself, whereby we will not proactively mention our differences,” Chen says.

Chen and Yi are not critical of the artists or audiences who partake in this “overcoming narrative,” recognizing that earning a livelihood from art often requires practical considerations. Many performers are simply giving audiences what they expect.

But both women are also assured of the alternative paths they have chosen, as it upholds their artistic integrity.

Chen says that her headstrong personality and her brush with mortality have only lifted the artistic standards that she aspires to. Describing herself as a perfectionist, she says that she does not want people to buy her pottery out of pity, but hopes that her work can stand on its own.

For Yi, an artistic practice that is grounded in the “overcoming narrative” is limiting, as it can literally reduce the artistic vision to a medical diagnosis.

She recalls translating for a Taiwanese artist during a meeting with a gallery owner in Chicago. The visiting artist explained that she has muscular dystrophy and created her pieces “little by little.” After an expectant pause, Yi realized that the artist had no intention of articulating any artistic vision.

That said, she is not surprised at the lack of a disability discourse in Taiwan’s art scene.

“I feel like I do get to make art and talk about my art more in the States,” Yi says. “Whenever I go back to Taiwan, I feel like I put on a different hat.”

Yi usually finds herself playing the role of disability activist, art administrator and disability studies scholar in Taiwan.

“The fact is there are a lot of barriers within arts and culture venues, so I feel like before we can really talk about forming a disability arts movement in Taiwan, we have to address accessibility as the core issue first,” Yi says.

BASIC BARRIERS

At the urging of disability rights groups, the government has in recent years introduced measures to ensure that the disabled community faces fewer obstacles to accessing cultural resources.

Current efforts are focused on making basic accessibility features such as wheelchair access and captions a fixture in arts and culture venues.

At the government’s encouragement, art institutions are also starting to tailor cultural programming for disabled audiences. For example, the National Museum of Taiwan Literature last week announced the launch of community resource boxes offering sensory experiences to facilitate blind and deaf visitors’ engagement with works of literature. The museum worked with representatives from the disabled community to design the boxes.

Most in the disabled community feel that such improvements are necessary and long overdue.

Huang Yu-hsiang (黃裕翔) won a Golden Horse award in 2012 for portraying himself in Touch of the Light (逆光飛翔), a movie about a blind music student who is a piano prodigy. Even years after the movie brought his daily challenges and experiences to a mainstream audience, he agrees that Taiwan still has a long way to go when it comes to accessibility.

“It’s always felt like Taiwan is slow at improving on accessibility. For the visually impaired to have environments where there are no barriers, I think there is still a lot of room for improvement,” Huang says.

Yang Sheng-hung (楊聖弘), a psychologist who is visually impaired, says that while accessibility in Taipei’s arts and culture venues has improved compared to a decade ago, there is still a great discrepancy between the city and rural areas.

He says the key is for non-disabled audiences and arts and culture providers to understand the needs of disabled people.

“We must understand that disabled people are just people. As long as it is part of the human condition to enjoy leisure activities and aesthetic experiences, this will not change just because someone is disabled,” Yang says.

The conversation about disability in Taiwan is relatively new, and the surest way to bring about real change is to pay attention to what members of the disabled community themselves are saying and doing.

“The way that disabled people have interacted with each other, the way that we have cared for each other, this interdependency relationship can be the base for us to nourish a set of vocabulary and understanding when we live, when we create, when we work with each other,” Yi says.

June 23 to June 29 After capturing the walled city of Hsinchu on June 22, 1895, the Japanese hoped to quickly push south and seize control of Taiwan’s entire west coast — but their advance was stalled for more than a month. Not only did local Hakka fighters continue to cause them headaches, resistance forces even attempted to retake the city three times. “We had planned to occupy Anping (Tainan) and Takao (Kaohsiung) as soon as possible, but ever since we took Hsinchu, nearby bandits proclaiming to be ‘righteous people’ (義民) have been destroying train tracks and electrical cables, and gathering in villages

Dr. Y. Tony Yang, Associate Dean of Health Policy and Population Science at George Washington University, argued last week in a piece for the Taipei Times about former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) leading a student delegation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that, “The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world” (“Ma’s Visit, DPP’s Blind Spot,” June 18, page 8). Yang contends that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has a blind spot: “By treating any

Swooping low over the banks of a Nile River tributary, an aid flight run by retired American military officers released a stream of food-stuffed sacks over a town emptied by fighting in South Sudan, a country wracked by conflict. Last week’s air drop was the latest in a controversial development — private contracting firms led by former US intelligence officers and military veterans delivering aid to some of the world’s deadliest conflict zones, in operations organized with governments that are combatants in the conflicts. The moves are roiling the global aid community, which warns of a more militarized, politicized and profit-seeking trend

This year will go down in the history books. Taiwan faces enormous turmoil and uncertainty in the coming months. Which political parties are in a good position to handle big changes? All of the main parties are beset with challenges. Taking stock, this column examined the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) (“Huang Kuo-chang’s choking the life out of the TPP,” May 28, page 12), the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) (“Challenges amid choppy waters for the DPP,” June 14, page 12) and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) (“KMT struggles to seize opportunities as ‘interesting times’ loom,” June 20, page 11). Times like these can