On October 7, the Evergreen Maritime Museum (長榮海事博物館) in Taipei marked its tenth anniversary. The artifacts collected and displayed here explore various aspects of humanity’s interaction with the oceans, and will appeal to anyone interested in history or engineering or both.

Located where Ketagalan Boulevard and Zhongshan South Road (中山南路) meet with Renai Road (仁愛路) and Xinyi Road (信義), the museum couldn’t be any more central. It faces the Presidential Office, and NTU Hospital Metro Station is a 10 minute walk away.

The museum belongs to the Chang Yung-fa Foundation, created by and named for the tycoon who established the Evergreen Group (長榮集團), a Taiwanese conglomerate that includes a global shipping business and the airlines EVA Air and UNI Air.

Photo courtesy of Evergreen Maritime Museum

MODEL BOATS

Chang Yung-fa (張榮發, 1927–2016) began working on ships when he was 18, and bought his first vessel in 1968. When his businesses began to flourish, long before he considered opening a museum, Chang began collecting maritime relics. He was particularly interested in models of boats and ships, and for many visitors these fabulously detailed mockups are the most memorable part of the museum.

More than a score of models represent ships that have been part of Evergreen’s fleet. The company was one of the first to embrace containerization, and for a period it was the world’s top container shipping line. With around 200 vessels, it remains among the world’s top six shippers in terms of market share.

Photo: Steven Crook

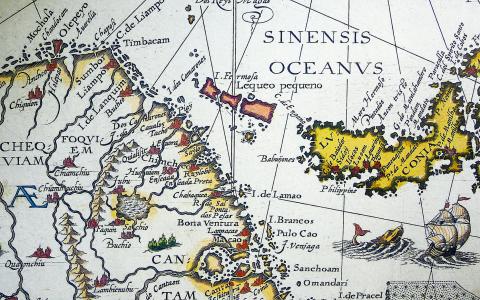

Thankfully, the museum goes far beyond corporate propaganda. In keeping with its stated mission — “to preserve and present the history, art and science of boats and ships, in the hope of generating public interest in maritime culture” — the museum also displays maps of historical importance, oil paintings and items like a collapsible liferaft, which younger visitors like to climb aboard. The only facet of human activity on the oceans which the museum doesn’t cover is piracy.

During his lifetime, Chang donated his collection of 4,500 items to the museum. Around 600 of them are now on display.

Of the four vessels displayed in the lobby, the two most interesting are a traditional fishing boat made and used by the indigenous inhabitants of Taiwan’s Orchid Island (Lanyu, 蘭嶼), and an authentic Arabian dhow. A Dubai-based friend of Chang’s helped him arrange the building of the dhow in the mid-1990s.

Photo: Steven Crook

Visitors are advised to proceed from the lobby to the fifth floor, then work their way downstairs. This way, they’ll begin with humanity’s most ancient watercraft. Among them are a coracle from the British Isles, an inflated goat skin (a way of crossing rivers in Assyria), a Maori waka, a Taiwanese bamboo raft and the kind of flat-bottomed coastal boat still common in the Philippines.

Also represented are oar-powered triremes like those that fought sea battles in the Mediterranean as recently as the 18th century, and Viking longships. Unlike many seacraft, which need space and time to turn around, the latter could reverse out of a tight spot at the drop of a horned helmet. Whereas most wooden ships are carvel-built, meaning the hull planks are fastened edge to edge, longships were clinker-built, the edges of hull planks overlapping each other, like weatherboard on the side of a house.

Several of the models on this floor, including those of the Mayflower and the Golden Hind, were individually ordered by Chang and crafted by renowned Japanese miniature-ship builder Toshio Uchiyama. Others were purchased at auctions.

Photo: Steven Crook

Here I learned that junk (the name given to a type of ancient Chinese sailing ship) is properly pronounced “yoonk.” The word may be of Chinese or Old Javanese origin. Because of their shallow draft, junks were ideal for sailing up rivers and along coastlines (like Taiwan’s west coast) littered with shoals and sandbars. Their sails were often made of bamboo slats rather than cloth.

Visitors can also find the Great Eastern, one of three ships designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel (an engineer better known for railways, and named the second-greatest Briton ever in 2002 poll organized by the BBC). The largest ship ever when launched in 1858, the Great Eastern could sail from the UK to Australia and back without refuelling, carrying 4,000 passengers. For economic reasons it never did, however, instead crossing the Atlantic several times, then finding greater success after being converted to a telegraph cable-laying ship.

Another display is devoted to “king boats” — highly decorated vessels burned for religious reasons during triennial rituals at various places in southern Taiwan — complete with a model “king boat” by Tseng Shu-min (曾樹銘). To craft this replica, Tseng drew on his experience making real “king boats” in Donggang (東港) in Pingtung.

Photo: Steven Crook

There is a replica of one of the most important carvel-built ships in history, Santa Maria, the flagship when Columbus crossed the Atlantic Ocean in 1492. The story of the Vasa, a Swedish warship that was fabulously expensive for its era, is less well known. It sank on its maiden voyage in 1628, but was salvaged in 1961 and turned into a tourist attraction.

TITANIC RELIC

The oddest relic on this floor is of dubious authenticity, yet compelling. A notebook-sized piece of wooden planking, it bears a message purportedly scratched by John Jacob Astor IV as he faced certain death during the sinking of the RMS Titanic in 1912.

Astor, a member of one of the richest families in the US, and his wife were returning to New York after a honeymoon in Europe. After the ship collided with an iceberg, Astor’s pregnant wife, maid and nurse boarded a lifeboat; all three survived, thanks to the “women and children first” principle. Astor, it is said, then etched this goodbye. Since it was discovered on a beach in Canada, this collectible has changed hands several times, yet the Astor family has never accepted it as genuine.

The third floor is divided between Maritime Taiwan and Marine Paintings. The grandest of the maritime-themed paintings is titled The Japanese Fleet Offshore with Mount Fuji Rising Beyond. In the 1890s, British artist William Wyllie was commissioned by the Imperial Japanese Navy to produce a large painting of its fleet with the country’s most famous landscape. The watercolor displayed in Taipei is a study Wyllie did while working on the version in oils that still belongs to Japan’s royal family.

A 1983 oil painting showing USS Intrepid attacked by Japanese kamikaze planes is notable for the tiny mermaid, looking on from the surface of the sea.

Much of the equipment displayed on the second floor (Navigation and Exploration) was taken from ships being retired from Evergreen’s fleet. Here, you’ll learn about working conditions on modern ships, reflecting Chang’s wish to encourage young people to pursue careers in the merchant marine.

Sailors are away from home for months on end, and now loading and unloading are done so quickly there’s little time to explore ports of call. Nonetheless, salaries are attractive. A third officer working for Evergreen typically earns NT$130,000 per month; container-ship captains make a lot more than that. Venturing out onto the high seas is nowhere near as perilous as it used to be, but for skilled seafarers, there are substantial rewards.

Steven Crook has been writing about travel, culture, and business in Taiwan since 1996. Having recently co-authored A Culinary History of Taipei: Beyond Pork and Ponlai, he is now updating Taiwan: The Bradt Travel Guide.

Next week, candidates will officially register to run for chair of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). By the end of Friday, we will know who has registered for the Oct. 18 election. The number of declared candidates has been fluctuating daily. Some candidates registering may be disqualified, so the final list may be in flux for weeks. The list of likely candidates ranges from deep blue to deeper blue to deepest blue, bordering on red (pro-Chinese Communist Party, CCP). Unless current Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) can be convinced to run for re-election, the party looks likely to shift towards more hardline

Last week the story of the giant illegal crater dug in Kaohsiung’s Meinong District (美濃) emerged into the public consciousness. The site was used for sand and gravel extraction, and then filled with construction waste. Locals referred to it sardonically as the “Meinong Grand Canyon,” according to media reports, because it was 2 hectares in length and 10 meters deep. The land involved included both state-owned and local farm land. Local media said that the site had generated NT$300 million in profits, against fines of a few million and the loss of some excavators. OFFICIAL CORRUPTION? The site had been seized

Sept. 15 to Sept. 21 A Bhutanese princess caught at Taoyuan Airport with 22 rhino horns — worth about NT$31 million today — might have been just another curious front-page story. But the Sept. 17, 1993 incident came at a sensitive moment. Taiwan, dubbed “Die-wan” by the British conservationist group Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), was under international fire for being a major hub for rhino horn. Just 10 days earlier, US secretary of the interior Bruce Babbitt had recommended sanctions against Taiwan for its “failure to end its participation in rhinoceros horn trade.” Even though Taiwan had restricted imports since 1985 and enacted

Enter the Dragon 13 will bring Taiwan’s first taste of Dirty Boxing Sunday at Taipei Gymnasium, one highlight of a mixed-rules card blending new formats with traditional MMA. The undercard starts at 10:30am, with the main card beginning at 4pm. Tickets are NT$1,200. Dirty Boxing is a US-born ruleset popularized by fighters Mike Perry and Jon Jones as an alternative to boxing. The format has gained traction overseas, with its inaugural championship streamed free to millions on YouTube, Facebook and Instagram. Taiwan’s version allows punches and elbows with clinch striking, but bans kicks, knees and takedowns. The rules are stricter than the