“Taiwan is Taiwan, Call Me Taiwanese” is the theme of the 13th Tsai Jui-Yueh International Dance Festival (第十三屆蔡瑞月國際舞蹈節), which will be held this weekend at Rose Historic Site (玫瑰古蹟), the Japanese-style house in Taipei that was Tsai’s China Dance Club for decades.

This year’s festival aims to celebrate Tsai’s legacy as well as commemorate the 70th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights with a selection of works that includes a new piece about the plight of refugees.

Tsai, who died in exile in Australia in 2005, was a pioneer of modern dance in Taiwan, but her legacy extends far beyond the usual confines of stage and theater; it serves as a reminder that dance, like other arts, can be a potent force for protest and social commentary, as well as cultural exchange.

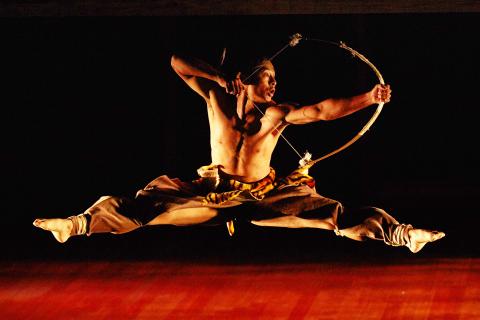

Photo courtesy of Pan Jia-huang

The Tainan-born Tsai, who went to Japan in 1937 at the age of 16 to pursue her dance studies, returned to Taiwan in 1946 and began teaching and performing, often for the newly arrived troops of the newly arrived Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) government.

She married Indonesian-born Chinese poet, professor and newspaper publisher Lei Shih-yu (雷石榆) in 1947, but in June 1949 he was arrested by the government for spying for the Chinese Communist Party and expelled from Taiwan.

A plan for Tsai, Lei and their son to reunite in Hong Kong was halted by the government, which first told Tsai she could not leave and later arrested and jailed her on Green Island for three years.

Photo courtesy of Liu Yan-nan

After her release, Tsai returned to Taipei, teaching and performing, despite being tightly monitored by security forces. She was not allowed to leave the country until 1983, when she moved to Australia to join her son, Roc Lei Ta-peng (雷大鵬), who was working there as a dancer.

She left the China Dance Club in the hands of two former students, her daughter-in-law, Ondine Hsiao (蕭渥廷), who now chairs the Tsai Jui-Yueh Dance Foundation, and her sister, Grace Hsiao (蕭靜文), whose founded her eponymous troupe in 1985 to both to perform her own work and preserve that of Tsai’s.

Even after Tsai’s departure, the studio remained ensnared in politics. The Taipei City Government had planned in 1994 to demolish it, but a campaign was launched to preserve it as a tribute to Tsai and her work. It was finally designated a municipal historic site on Oct. 22, 1999, but just four days later it burned down — while Tsai was on her only second visit back to Taipei since leaving — an arson case that has never been solved.

The rebuilt studio was finished in November 2003, and in 2005 it was renamed the Rose Historic Site in honor of one of Tsai’s most famous works, The Prison and the Rose. Three years later the first Tsai Jui-Yueh International Dance Festival was held.

For the festival performances, the sliding doors at the front of the house are pushed back so the front room and wooden walkway can serve as a stage, with the audience seated in the garden.

The festivals, held the first weekend in November, have always celebrated not only Tsai works, but those of her Japanese teacher, Ishii Baka, and choreographers whom Tsai admired or echoed her passion for socially relevant dance.

By continuing to promote her work, as well as those by other socially minded choreographers, the foundation hopes to promote social reform and democracy in Taiwan.

Reconstructing the works of Tsai and others help preserve the links between generations of dancers, reminding young Taiwanese dancers of their lineage, of the links between teachers and students, choreographers and performers, as well as how works can relate to humanity and social issues.

This year is no different. The nine works on the program include a new work, Refugee by Australian Elizabeth Dalman, who first met Tsai during a tour of Taiwan in 1971.

Tsai sent her son to Australia to study with Dalman and he later worked for her for four years at the Australian Dance Theatre.

Dalman said Ondine Hsiao asked her to create a work about the worldwide refugee problem.

“I was surprised that she asked me, because Taiwan does not have this problem,” Dalman said in a telephone interview last week. “Traveling in Europe I have seen the refugee and migrant problems, and Australia has a very brutal policy.”

“There are 68 million people forced out of their homes because of war, environmental degradation, famine — of these 25 million are refugees. Then there is the Rohingya crisis, and the refugee problem will probably get worse as climate change continues.”

After hearing people from Doctors Without Borders talk about the refugees in Nauru — those who have been stopped from reaching Australia and sent to a camp on that island nation — as “destroyed,” Dalman said she wanted to call her work “Flight for Life,” but there was already publicity material titling it Refugee, so she could not change it.

“I am using a Taiwanese actor and nine dancers, plus one of my dancers from my company [the Mirramu Dance Company], because I wanted a mix of people to show refugees are a worldwide problem,” she said.

The centerpiece of the program is Colombian-American Eleo Pomar’s 1967 classic Las Desenamordas, a powerful work about the repression of women, based on Spanish author and playwright Federico Garcia Lorca’s final play, The House of Bernard Alba, set to a score by John Coltrane.

Dalman was the link between Tsai and Pomar, as he was her mentor when she studied in the US in the 1960s, transitioning from ballet to modern dance, and Ondine Hsiao asked him to create a work for one of the first Tsai Jui-Yueh festivals after seeing one of his pieces during a trip to Australia in 2002.

Chasing (追), Tsai’s 1949 work inspired by the Thao, was one of the first modern dances to honor Taiwan’s Aboriginal culture and the nation’s landscape. It recounts the Thao legend of how a hunter was chasing a white deer and discovered Sun Moon Lake, leading the Thao to move from Alishan to the lake.

Three of the works are by Ishii Baka, created between 1925 and 1926, including White Gloves, set on three dancers and performed without music, and two works that will be performed by his grandson, one of which is a solo that is just one minute and 26 seconds long, Grace Hsiao said.

In addition to the actual performances, the festival includes an opening ceremony tomorrow morning and a seminar in the afternoon. Representatives from dozens of local non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are invited to the ceremony, which will include a prayer by a minister for Taiwan, as well as a procession that circles the studio site three times, with the NGO people carrying the banners of their groups.

More information on the festival and the Rose Historic Site can be found on the Tsai Jui-yueh Dance Research Institute’s Web site (sites.google.com/dance.org.tw/studio).

However, the times of the performances on the site are not correct. Grace Hsiao said the shows start at 7:45pm, not 7:30pm, because they have learned from experience to give the city garbage trucks, which arrive about 7:35pm, time to move through the alleys around the studio so their music does not disturb the performances.

It’s a good thing that 2025 is over. Yes, I fully expect we will look back on the year with nostalgia, once we have experienced this year and 2027. Traditionally at New Years much discourse is devoted to discussing what happened the previous year. Let’s have a look at what didn’t happen. Many bad things did not happen. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) did not attack Taiwan. We didn’t have a massive, destructive earthquake or drought. We didn’t have a major human pandemic. No widespread unemployment or other destructive social events. Nothing serious was done about Taiwan’s swelling birth rate catastrophe.

Words of the Year are not just interesting, they are telling. They are language and attitude barometers that measure what a country sees as important. The trending vocabulary around AI last year reveals a stark divergence in what each society notices and responds to the technological shift. For the Anglosphere it’s fatigue. For China it’s ambition. For Taiwan, it’s pragmatic vigilance. In Taiwan’s annual “representative character” vote, “recall” (罷) took the top spot with over 15,000 votes, followed closely by “scam” (詐). While “recall” speaks to the island’s partisan deadlock — a year defined by legislative recall campaigns and a public exhausted

In the 2010s, the Communist Party of China (CCP) began cracking down on Christian churches. Media reports said at the time that various versions of Protestant Christianity were likely the fastest growing religions in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The crackdown was part of a campaign that in turn was part of a larger movement to bring religion under party control. For the Protestant churches, “the government’s aim has been to force all churches into the state-controlled organization,” according to a 2023 article in Christianity Today. That piece was centered on Wang Yi (王怡), the fiery, charismatic pastor of the

Hsu Pu-liao (許不了) never lived to see the premiere of his most successful film, The Clown and the Swan (小丑與天鵝, 1985). The movie, which starred Hsu, the “Taiwanese Charlie Chaplin,” outgrossed Jackie Chan’s Heart of Dragon (龍的心), earning NT$9.2 million at the local box office. Forty years after its premiere, the film has become the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute’s (TFAI) 100th restoration. “It is the only one of Hsu’s films whose original negative survived,” says director Kevin Chu (朱延平), one of Taiwan’s most commercially successful