Oct. 28 to Nov. 4

Naosuke Tomita was a retired major general when he left Japan; by the time he arrived in Taiwan on Nov. 1, 1949, he was known as Pai Hung-liang (白鴻亮). His companion, captain Kunimitsu Aratake, also assumed a new identity as Lin Kuang (林光).

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) leader Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石), who had been staying in Taipei’s Yangmingshan since June, met with Tomita on Nov. 3, according to a single-sentence entry in his diary. They met again on Nov. 13, where they “drank tea and chatted freely.”

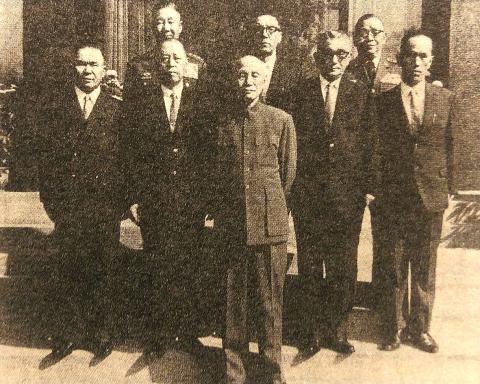

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

This was the tail end of the Chinese Civil War, and Chiang headed back to China for one last time on Nov. 14. Tomita and Aratake followed him a few days later, and were assigned to the frontlines in western China.

Tomita would become the leader of what would be known as the White Group (白團), a clandestine team of Japanese military advisers to the KMT. After the war, he remained in Taiwan even after the White Group disbanded in 1969, dying on vacation in Tokyo in 1979. Half of his ashes were kept in Japan, with the other half being stored upon his request at Haiming Temple (海明寺) in New Taipei City’s Shulin District (樹林).

CHIANG’S MOTIVES

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Aside from the Communists, the Japanese were probably Chiang’s most hated enemies, as the two sides fought for eight years in China. So it seems unusual that Chiang would ask for their help after the war, especially when the KMT actively tried to root out all Japanese influence among the Taiwanese, who they described as “deeply poisoned” by foreign imperialism.

The common explanation is that the Japanese soldiers wanted to repay Chiang for his kindness toward Japan, as he did not ask for war reparations and allowed Japanese civilians and soldiers to leave China and Taiwan peacefully.

“But when you really start digging, you start wondering, were these people really operating under such pure and naive motives and principles?” writes Tsuyoshi Nojima in the introduction to his book, The Last Imperial Soldiers: Chiang Kai-shek and the White Group (最後的帝國軍人:蔣介石與白團).

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

In fact, Chiang’s connection with Japan goes beyond his conflict with them, as he attended military school in Tokyo and served in the Imperial Japanese Army from 1909 to 1911 before returning to China to help overthrow the Qing Dynasty.

Nojima writes that Chiang was impressed by the Japanese army’s rigorous and spartan training, which played a key role in the establishment of the White Group. The Chinese army was weak in comparison, and he believed that military education was one of the main differences.

This belief persisted even after the Japanese defeat.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“Politically, Japan was the KMT’s former enemy, and anti-Japanese sentiments were still high among the Chinese,” Nojima writes. “Chiang could not act openly, but as the situation worsened for the KMT [against the Communists], survival was a priority. Thus, asking the Japanese for military assistance after he retreated to Taiwan was his secret plan out of all his secret plans.”

UNITED AGAINST THE RED DEVILS

Despite commanding the China Expeditionary Army during the Japanese invasion of China and being responsible for countless atrocities, General Yasuji Okamura was found not guilty by the Shanghai War Crimes Tribunal after World War II. Instead, Chiang recruited him as a military adviser.

The day after Japanese surrender, Okamura pondered the future of East Asia in his diary, writing: “Right now, the only hope is for China to be strong and prosperous. For Japan, the losers, all we can do is provide technical help and share our experience.”

Among the KMT officers sent to discuss the Japanese surrender ceremony with Okamura was Tsao Shih-cheng (曹士澂), who would later become the White Group’s contact person in Taiwan. Nojima postulates that the idea of “working with Japanese soldiers to fight the communists” was likely sown during this time.

Tsao’s role was kept top secret until he handed his personal account of the White Group formation to historian Chen Peng-jen (陳鵬仁), who passed it on to Nojima. Tsao headed to Japan in April 1949 nominally to work at the Republic of China Embassy. But he had a secret mission to work with the Japanese military to find ways the KMT could turn the tide against the Communists.

Tsao’s first idea was to recruit Japanese soldiers into a “International Anti-Communist United Army,” but he scrapped the plan in fear of angering the US. Instead, he suggested forming a military consultant group, which Chiang approved in July 1949.

On Sept. 10, 1949, the two sides signed the cooperation agreement with the goal of “defeating the Red Devils,” with Tsao as the KMT representative and Tomita as his counterpart. Okamura signed his name as the guarantor. To avoid detection, the words “military” and location of service were blotted out in the contract. The members were offered a lucrative salary with additional money provided to their families.

Tomita, who was hailed as a military genius during his cadet years and fought in southern China during the war, was appointed leader of the group. He shaved off his mustache — considered a uniquely Japanese feature — and adopted the surname Pai (白), which means “white,” to contrast with their “red” enemies. This also gave rise to the group’s name.

Tomita and Aratake surveyed the KMT troops at the frontlines and submitted a report to the KMT top brass in Chongqing, who highly valued their opinion and engaged them in many discussions. However, the exercise was futile. They were ordered to fly to Taiwan on Nov. 28, 1949, and Chongqing fell two days later. On Dec. 10, Chiang also fled to Taiwan, never to set foot in China again.

The rest of the White Group had arrived in Taiwan just a few days before Chiang, beginning their work immediately.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

June 23 to June 29 After capturing the walled city of Hsinchu on June 22, 1895, the Japanese hoped to quickly push south and seize control of Taiwan’s entire west coast — but their advance was stalled for more than a month. Not only did local Hakka fighters continue to cause them headaches, resistance forces even attempted to retake the city three times. “We had planned to occupy Anping (Tainan) and Takao (Kaohsiung) as soon as possible, but ever since we took Hsinchu, nearby bandits proclaiming to be ‘righteous people’ (義民) have been destroying train tracks and electrical cables, and gathering in villages

Dr. Y. Tony Yang, Associate Dean of Health Policy and Population Science at George Washington University, argued last week in a piece for the Taipei Times about former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) leading a student delegation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that, “The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world” (“Ma’s Visit, DPP’s Blind Spot,” June 18, page 8). Yang contends that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has a blind spot: “By treating any

Swooping low over the banks of a Nile River tributary, an aid flight run by retired American military officers released a stream of food-stuffed sacks over a town emptied by fighting in South Sudan, a country wracked by conflict. Last week’s air drop was the latest in a controversial development — private contracting firms led by former US intelligence officers and military veterans delivering aid to some of the world’s deadliest conflict zones, in operations organized with governments that are combatants in the conflicts. The moves are roiling the global aid community, which warns of a more militarized, politicized and profit-seeking trend

This year will go down in the history books. Taiwan faces enormous turmoil and uncertainty in the coming months. Which political parties are in a good position to handle big changes? All of the main parties are beset with challenges. Taking stock, this column examined the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) (“Huang Kuo-chang’s choking the life out of the TPP,” May 28, page 12), the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) (“Challenges amid choppy waters for the DPP,” June 14, page 12) and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) (“KMT struggles to seize opportunities as ‘interesting times’ loom,” June 20, page 11). Times like these can