Sept. 17 to Sept. 23

Teng Sheng (鄧盛) stood before the Tokyo District Court on Feb. 5, 1979. Even though he had lost an eye, an arm and the hearing in his right ear while serving in the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II, it was his first time to visit Japan.

“The problem of compensation has not been resolved since the war. You’ve been wanting to come here and plead your case since then, correct?” the examiner asked.

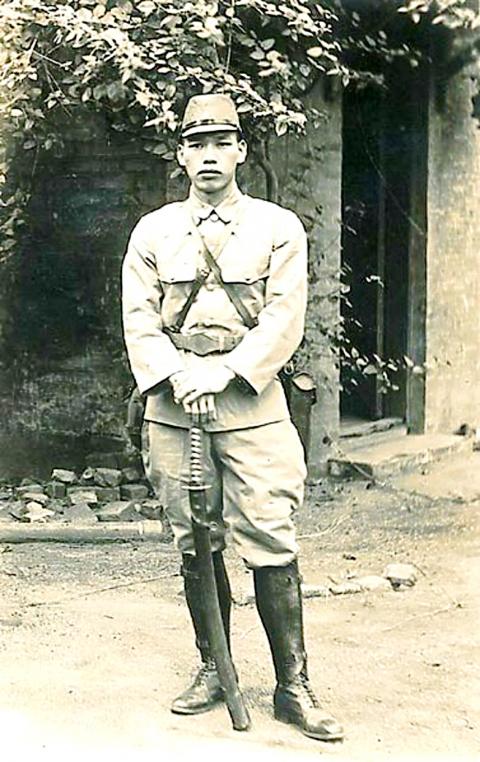

Photo: Chen Feng-li, Taipei TImes

“Yes. Ever since the war, I’ve wanted to,” Teng replied, recalling how he wrote a letter in 1952 to the Japanese Embassy immediately after it was established in Taipei. The Japanese replied that according to the Treaty of Taipei, all war claims “shall be the subject of special arrangements between the government of the Republic of China and the government of Japan” and there was nothing they could do since Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) announced at the end of the war that he would not seek war reparations from Japan.

It took years of lawsuits and campaigns for the Japanese to take any action, finally enacting a special law on Sept. 18, 1987, to pay 2 million yen to each former Taiwanese soldier severely wounded in battle as well as the families of those who perished. It was a fraction of the lump sum that Japanese soldiers received, who were also paid an annual allowance.

FARMING UNDER FIRE

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Japanese statistics released in 1973 show that 207,183 Taiwanese served in the Japanese Army between 1937 and 1945, with a total of 30,304 casualties. Although the Japanese did not conscript Taiwanese until January 1945, they managed to recruit them to help the war efforts through various means. According to the book War Experiences of the Taiwanese Soldiers of Japan (台灣人日本兵的戰鬥經驗), most of them were not official soldiers, but auxiliary forces performing tasks such as transporting arms and helping with agriculture in occupied areas.

Since official recruitment and conscription only happened at the tail end of the war, these soldiers were mostly tasked with defending Taiwan, and few entered the battlefield.

Teng was 16 in 1937 when the war between China and Japan formally broke out. From then on, he had to participate in youth group activities about once a month, which included military training and Japanese nationalist indoctrination.

In 1943, he was summoned to a local district office, where he was told to travel “south” as an agricultural technician for the army. He had just gotten married, and his father was aging. As the only son, Teng thought, he should be at home looking after his family.

“But I could not refuse,” Teng said. “Our education and training up to that point emphasized putting country first, that our bodies are meant to service the country and the emperor. I believed in this fully and even though I did not want to go, I felt that I had to. I did not have any thoughts of avoiding my duty.”

In July, 50 recruits gathered at the port of Kaohsiung. “Starting from today, you are members of the Imperial Army,” an officer announced. “You are to give your life for the emperor. Do not worry about your families as the country will take care of them.”

Teng’s destination was Rabaul in today’s Papua New Guinea. Upon arrival, they began clearing a former German coconut farm to plant vegetables. There was some bombing by the Allies at night, but everything was mostly peaceful. But the air raids intensified a few months later. Teng would hide when the fighters came, and continue farming after they left. In August 1944, Teng was tasked with transporting seeds and farm tools to another site. As the team leader, he stayed behind to count the goods, and on his way back to the forest shelter, Allied fighters appeared.

The last thing Teng remembers was a sharp pain in his shoulder; he later woke up in the hospital. He remained in Papua New Guinea until the end of the war, upon which he was taken by the Allies and sent back to Taiwan.

NOT ELIGIBLE

In 1972, the Japan broke diplomatic ties with Taiwan, and the Treaty of Taipei was terminated. This meant that Taiwanese who helped the Japanese with the war effort could fight for compensation. But the real turning point was in December 1974, when an Aboriginal soldier in the Japanese Army named Suniuo was found on the Indonesian island of Morotai, bringing the issue of former Taiwanese soldiers to the public eye.

While Suniuo received money from the Japanese, it was a pittance in comparison to what Japanese in the same situation received, which drew the attention of both Japanese and Taiwanese.

“If [Suniuo] receives compensation, then so should we,” Teng said. “We fought bravely under the Japanese flag alongside the Japanese — especially those of us who were tasked with transporting food to the soldiers. We didn’t stop even during the regular bombings. If the Japanese government doesn’t compensate us, then the trust and righteousness that Japanese teachers taught us is meaningless.”

Teng said it was difficult to get the Japanese to issue his war injury record. When he did finally receive it, they still refused to compensate him for his injuries.

When asked to state his feelings in court, Teng said: “It’s the fault of the Japanese that my body is like this now. I did not cause this. And when Japan lost the war, I was suddenly no longer a Japanese citizen. I don’t understand why those Japanese who suffered the same fate as me received help, while us Taiwanese got nothing.”

While the Japanese court appeared sympathetic during Teng’s hearing, in February 1982 it ruled that Taiwanese soldiers were not eligible for any compensation because they were no longer Japanese citizens. This actually drew more Japanese to their cause, and politicians started paying attention, even convincing more than 60 percent of the Japanese Diet members to sign a petition, finally leading to its 1987 decision.

“We could applaud the ‘humanitarian spirit’ of the Japanese, but as the [Taiwanese soldiers] are still not treated the same as their comrades, it can’t be considered humane … But this is a first step that has opened a door after decades of struggle…” wrote historian Yin Chang-yi (尹章義) for the China Times (中國時報) on Sept. 22, 1987.

But there wasn’t much progress afterward, and the issue has yet to be resolved.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Taiwan has next to no political engagement in Myanmar, either with the ruling military junta nor the dozens of armed groups who’ve in the last five years taken over around two-thirds of the nation’s territory in a sprawling, patchwork civil war. But early last month, the leader of one relatively minor Burmese revolutionary faction, General Nerdah Bomya, who is also an alleged war criminal, made a low key visit to Taipei, where he met with a member of President William Lai’s (賴清德) staff, a retired Taiwanese military official and several academics. “I feel like Taiwan is a good example of

March 2 to March 8 Gunfire rang out along the shore of the frontline island of Lieyu (烈嶼) on a foggy afternoon on March 7, 1987. By the time it was over, about 20 unarmed Vietnamese refugees — men, women, elderly and children — were dead. They were hastily buried, followed by decades of silence. Months later, opposition politicians and journalists tried to uncover what had happened, but conflicting accounts only deepened the confusion. One version suggested that government troops had mistakenly killed their own operatives attempting to return home from Vietnam. The military maintained that the

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades

Lori Sepich smoked for years and sometimes skipped taking her blood pressure medicine. But she never thought she’d have a heart attack. The possibility “just wasn’t registering with me,” said the 64-year-old from Memphis, Tennessee, who suffered two of them 13 years apart. She’s far from alone. More than 60 million women in the US live with cardiovascular disease, which includes heart disease as well as stroke, heart failure and atrial fibrillation. And despite the myth that heart attacks mostly strike men, women are vulnerable too. Overall in the US, 1 in 5 women dies of cardiovascular disease each year, 37,000 of them