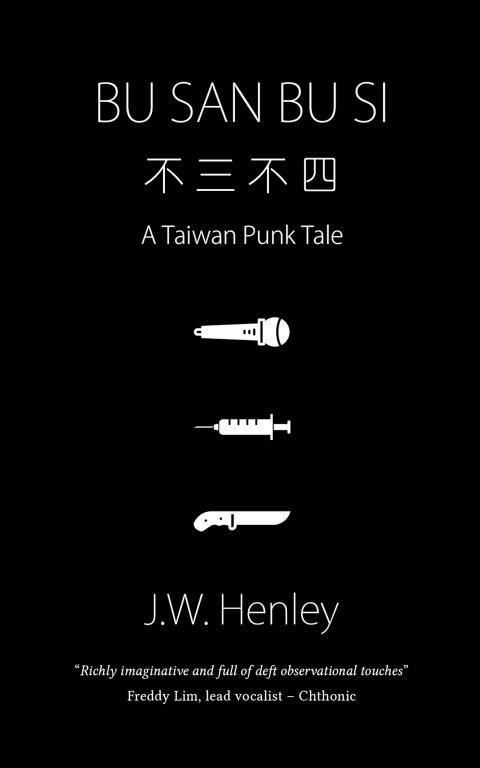

Bu San Bu Si (不三不四) or “not three, not four” — a Mandarin expression used to describe society’s misfits and lowlifes — is the second novel by Canadian freelance writer and heavy metal rocker Joe Henley. Having spent the last 12 years in Taipei playing with metal and punk bands and chronicling the scene for publications such as this newspaper, Henley takes his readers where we otherwise would not venture — to live music venues that are “perpetually covered in mildew mold” and recording studios with “years of stale sweat ... soaked into the walls.” Yet despite being about Taiwan’s underground punk music scene, the novel speaks to anyone who has experienced the pressure of conforming to a dominant culture that he or she finds stifling.

While Henley’s first novel, Sons of the Republic, featured a well-to-do Taiwanese-American protagonist who squanders his money from his penthouse in Taipei’s posh Xinyi District, the characters in Bu San Bu Si are born into a world where they are expected to slug it out at desk jobs to support blue-collar parents who operate night market stands or work the night shift at hospitals. Henley deftly delves into their psyche and motivations, providing us with a glimpse into a world that’s rarely written about in English.

TOUGH LUCK

Henley’s protagonist, 20-year-old guitarist Xiao Hei, wears a beat-up leather jacket, even during the sweltering heat of Taipei’s summer, and eschews his responsibility as a “golden son” who is supposed to provide for his mother. He drifts away from childhood friends and aspiring musicians who have all “faded away into civilian life.” Having never traveled outside of Taiwan, Xiao Hei has lofty dreams of performing in countries whose names he reads on the labels of liquor bottles. But he drinks, gets into fist fights and constantly shows up late for band practice.

Xiao Hei’s actions may seem reprehensible and inexcusable. But, as readers learn, advice like “just be yourself” or “follow your dreams” is nonsensical. As Henley fleshes out in brilliant and grotesque prose, employing transliterations — and, of course, plenty of swear words — in Mandarin and Hoklo (more commonly known as Taiwanese), life isn’t easy for people like Xiao Hei, who was raised by a single, alcoholic mother who herself came from a troubled family. For Xiao Hei, shunning traditional Confucian values, pursuing his dream and simply being himself come with consequences that eventually get him mixed up with Taipei’s criminal underworld.

However, it’s not just gangsters who are corrupt. Like Sons of the Republic, the line separating criminals and law enforcement is blurred. As former gangster and bar owner Jackie Tsai tells Xiao Hei: “It’s a wicked little game, the law.” This is a lesson that is repeatedly knocked into Xiao Hei’s skull — literally and figuratively — starting from when he and his bandmates are publicly humiliated by politicians seeking to make an example of them. The men in “suits and ties” accuse the band of desecrating “Chinese values” and “aping the decadence of the invasive Western culture.” This is ironic because Westerners barely feature in the novel and it’s obvious that “Chinese values” are nothing but a hollow rallying call for politicians to further their own agendas, or parents to control their children.

At the heart of this fissure is a generational gap. Like most Taiwanese born after the end of Martial Law, Xiao Hei is cognizant of the fact that his mother grew up in a vastly different society, one in which aspiring for something other than a stable job was absurd. As Henley writes, “he knew she had beasts in her head she did her best to chase away — old beasts of older generations.” Politics lurks in the background of the novel, beyond the grasp of Xiao Hei and his bandmates. Xiao Hei fails to show up at a gig during the Sunflower Movement, thinking of “protest songs” as silly though the names of his band’s songs include Remember 228 and KMT, Suck My Dick.

Unlike in his first novel, Henley does not fixate on what Taiwanese identity means. Instead, a feeling of fatalism permeates Bu San Bu Si. Motions driving events are set in place by people more powerful than Xiao Hei and there is little that he and his friends can do to stop them. They are nothing more than “tiles on the mahjong board moved by the hands of the players.”

Though there is a good dose of blood-drenched imagery, the plot moves forward largely through the metaphorical demons that play out in Xiao Hei’s head. There is a simultaneous sense of acceptance of his place in society and a yearning for something bigger and better. Though Xiao Hei isn’t the most sympathetic character, it is his desire to make his mark on society that distinguishes him from those around him.

The novel’s backdrop is a Taipei described as “cockroach-infested” and a “basin-bound smog bowl.” This grittiness crushes down on Xiao Hei and sucks the life out of him but the experience of daily toil also feeds him with what will become the inspiration for his artistry. Henley paints a complex portrait of ordinary Taiwanese — outcasts, doomsdayers, dreamers — with a raw simplicity that’s relatable. Although the author might be reluctant to admit it, his message ultimately comes across as an age-old one, that sometimes, simply being yourself does, in fact, go a long way, and there’s nothing wrong with reiterating that.

>> The Bu San Bu Si launch party will take place at 3pm on May 13 at Vinyl Decision, 6, Ln 38, Chongde St, Taipei City (台北市崇德街38巷6號). The author will be holding a Q&A session and copies of the book will be on sale for NT$400. For more information, visit: fb.com/events/1976225935940623

US President Donald Trump may have hoped for an impromptu talk with his old friend Kim Jong-un during a recent trip to Asia, but analysts say the increasingly emboldened North Korean despot had few good reasons to join the photo-op. Trump sent repeated overtures to Kim during his barnstorming tour of Asia, saying he was “100 percent” open to a meeting and even bucking decades of US policy by conceding that North Korea was “sort of a nuclear power.” But Pyongyang kept mum on the invitation, instead firing off missiles and sending its foreign minister to Russia and Belarus, with whom it

When Taiwan was battered by storms this summer, the only crumb of comfort I could take was knowing that some advice I’d drafted several weeks earlier had been correct. Regarding the Southern Cross-Island Highway (南橫公路), a spectacular high-elevation route connecting Taiwan’s southwest with the country’s southeast, I’d written: “The precarious existence of this road cannot be overstated; those hoping to drive or ride all the way across should have a backup plan.” As this article was going to press, the middle section of the highway, between Meishankou (梅山口) in Kaohsiung and Siangyang (向陽) in Taitung County, was still closed to outsiders

Many people noticed the flood of pro-China propaganda across a number of venues in recent weeks that looks like a coordinated assault on US Taiwan policy. It does look like an effort intended to influence the US before the meeting between US President Donald Trump and Chinese dictator Xi Jinping (習近平) over the weekend. Jennifer Kavanagh’s piece in the New York Times in September appears to be the opening strike of the current campaign. She followed up last week in the Lowy Interpreter, blaming the US for causing the PRC to escalate in the Philippines and Taiwan, saying that as

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has a dystopian, radical and dangerous conception of itself. Few are aware of this very fundamental difference between how they view power and how the rest of the world does. Even those of us who have lived in China sometimes fall back into the trap of viewing it through the lens of the power relationships common throughout the rest of the world, instead of understanding the CCP as it conceives of itself. Broadly speaking, the concepts of the people, race, culture, civilization, nation, government and religion are separate, though often overlapping and intertwined. A government