It’s strange watching Silence knowing that the entire film was shot in Taiwan despite the story being set in southern Japan. The bulk of Martin Scorsese’s latest work is set in villages or indoors (and in a wooden cage), but every time they show a scene of the lush coast or rolling hills, one can’t help but wonder which part of Taiwan it was shot in.

You feel that you recognize some of the locales — that mountain scene must be Yangmingshan, that rocky coastline looks like Jinguashi — but you are not entirely sure because you’ve never been to southern Japan. Though strangely discordant, the feeling soon disappears as the stunning cinematography and compelling storytelling take over.

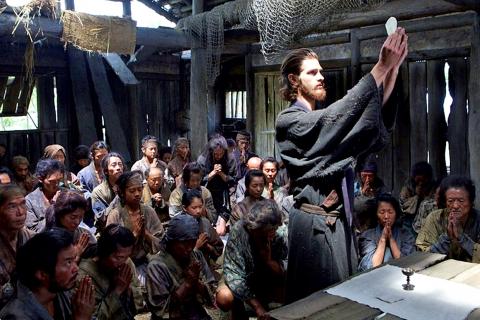

Years in the making, Scorsese’s passion project tells the story of two Jesuit priests (Andrew Garfield and Adam Driver) who arrive in 17th century Japan. Christians were being persecuted and executed, but believers continued to practice in secret. The plot follows the priests’ attempt to find their mentor (Liam Neeson), who is rumored to have apostatized and is living as a Japanese.

Photo courtesy of atmovies.com

It is is based on the 1966 novel of the same name by Shusaku Endo, who wrote from the rare perspective of a Japanese Roman Catholic. Endo himself is said to have endured religious discrimination in Japan.

Unsurprisingly, the story is heavily skewed toward the Western and Christian perspective, but that doesn’t mean it’s not enjoyable. Despite running 161 minutes, there’s enough emotion, tension, conflict and change of pacing in the film that there are few lulls.

The graphic composition of a few scenes remain memorable days after watching the film — a bird’s eye view of three priests, dressed in black, walking horizontally across the screen on a pure white stairway, a lone ship crashing through an ocean of dark blue. These can be incredibly detailed — during a cremation scene, the pyre is placed right in front of a rock, upon which the waves crash.

Silence comes in many symbolic forms throughout the film — the silence of God in response to the priest’s prayers, the silence of the people who risk death to practice in secret, and the silence of those who choose to internalize their faith instead of dying for it. It’s a trial for Father Rodrigues (Garfield), whose faith, which defines a way of life and all that he has known, is tested and he must decide how to move forward in a world where all odds are against him. This unyielding faith is what drives the film, as the tests become increasingly brutal. There’s a moral issue here — to what extent do you hold onto your faith when not only yours, but other people’s lives are at stake? Apostasy is just a formality here, and can be achieved by simply trampling on an image of Jesus. Does committing the act really mean you have turned your back on God?

We hold our breaths as things get worse, we wonder when Rodrigues is going to snap, and we question if we would ever have this kind of resolve.

While the Japanese characters are featured prominently with much dialogue that presents their reasons for wanting to rid the country of Christianity, it’s obvious that Scorsese wanted to portray them in a stark contrast to the priests’ holy characters. They are the bad guys who are merely obstacles to Rodrigues’ spiritual journey, and you don’t have much room to think otherwise.

You have the wretched, cowardly guide (Kubozuka Yousuke) who repeatedly betrays the heroes, the cruel and sarcastic translator (Asano Tadanobu) and finally the inquisitor (Ogata Issey), who is downright conniving and will do anything to achieve his goals. His high-pitched tone of voice, insincere facial expressions and irritating mannerisms make him immediately unlikeable, removing any chance for one to really ponder the Japanese perspective. This is unfortunate because there are some pretty intriguing metaphorical and philosophical exchanges between him and Rodrigues.

And the only “good” Japanese are the impoverished and oppressed villagers, the Hidden Christians, living in misery and revering the priests as saviors. They also seem like the only Japanese who were converted, a point which could have been explored more. We know what drives the priests, but what compels these villagers to choose death over spitting on a cross? What were their lives before the crackdown on Christianity?

The impressive thing is that these thoughts and comments only popped up after the film, indicating that it was a solid piece of entertainment. It’s a story that digs deep and can be deeply personal, even controversial, and each person will leave the theater with different questions.

One last thing: apparently Garfield and Driver were supposed to be talking in Portuguese-accented English. It didn’t work at all. Neeson, for his part, didn’t even try.

The canonical shot of an East Asian city is a night skyline studded with towering apartment and office buildings, bright with neon and plastic signage, a landscape of energy and modernity. Another classic image is the same city seen from above, in which identical apartment towers march across the city, spilling out over nearby geography, like stylized soldiers colonizing new territory in a board game. Densely populated dynamic conurbations of money, technological innovation and convenience, it is hard to see the cities of East Asia as what they truly are: necropolises. Why is this? The East Asian development model, with

June 16 to June 22 The following flyer appeared on the streets of Hsinchu on June 12, 1895: “Taipei has already fallen to the Japanese barbarians, who have brought great misery to our land and people. We heard that the Japanese occupiers will tax our gardens, our houses, our bodies, and even our chickens, dogs, cows and pigs. They wear their hair wild, carve their teeth, tattoo their foreheads, wear strange clothes and speak a strange language. How can we be ruled by such people?” Posted by civilian militia leader Wu Tang-hsing (吳湯興), it was a call to arms to retake

Desperate dads meet in car parks to exchange packets; exhausted parents slip it into their kids’ drinks; families wait months for prescriptions buy it “off label.” But is it worth the risk? “The first time I gave him a gummy, I thought, ‘Oh my God, have I killed him?’ He just passed out in front of the TV. That never happens.” Jen remembers giving her son, David, six, melatonin to help him sleep. She got them from a friend, a pediatrician who gave them to her own child. “It was sort of hilarious. She had half a tub of gummies,

The wide-screen spectacle of Formula One gets a gleaming, rip-roaring workout in Joseph Kosinski’s F1, a fine-tuned machine of a movie that, in its most riveting racing scenes, approaches a kind of high-speed splendor. Kosinski, who last endeavored to put moviegoers in the seat of a fighter jet in Top Gun: Maverick, has moved to the open cockpits of Formula One with much the same affection, if not outright need, for speed. A lot of the same team is back. Jerry Bruckheimer produces. Ehren Kruger, a co-writer on Maverick, takes sole credit here. Hans Zimmer, a co-composer previously, supplies the thumping