It powers everything we do, yet remains one of our biggest mysteries.

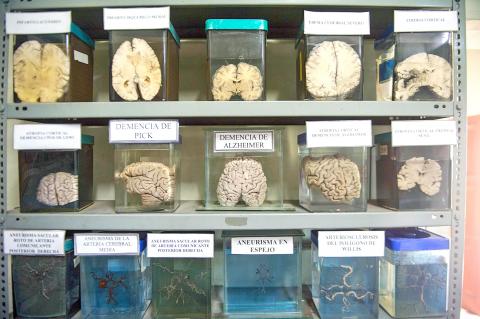

But thanks to an unusual Peruvian museum dedicated entirely to the brain, visitors can get up close and personal with the most complex organ in the human body.

The “brain library” at the Santo Toribio de Mogrovejo Hospital in Lima has a massive collection of diseased and healthy brains, giving researchers and also the general public a glimpse of what is going on inside our heads.

Photo: AFP / ERNESTO BENAVIDES

It is the only museum in Latin America, and one of the few in the world, with a large collection of brains that is regularly open to the public.

The hospital, which was founded more than three centuries ago, has a total of 2,912 brains collected over the years, nearly 300 of which are on display in a mind-opening exhibit.

Some 20,000 people visit the museum each year.

Photo: AFP / ERNESTO BENAVIDES

“Touch a real skull,” the museum invites them on arrival, proffering a specimen so visitors can feel the cranial bone structure and imagine how it holds two square meters of intricately folded brain matter.

The brains of this operation, so to speak, is neuropathologist Diana Rivas, who is hovering over an icy steel table choosing scientifically interesting specimens to add to the museum’s collection.

“This is where we do the autopsies. I handle them myself,” she tells AFP, barely looking up from the brain she is holding in her gloved hands.

She has just removed this particular specimen from a jar of formaldehyde.

It is about the size of a deflated football, and “has the consistency of a rubber eraser,” she says.

She examines the brain’s two hemispheres, which resemble giant walnuts, then carefully removes the thin layer of three membranes that hold them together, the meninges.

Once open, the organ’s fascinating geography is on full display: a labyrinth of gray and white tissue that holds the mysteries of thought, language and virtually every bodily function inside.

FOOD FOR THOUGHT

Rivas gives a lesson as she dissects.

“A human brain weighs between 1.2 and 2.4 kilos, depending on the height and weight of the person, and on the sex,” she says.

“Women’s are more evolved than men’s. What differentiates us is the evolution of language, which we use much more than men.”

The museum is divided into three parts: neuroanatomy, birth defects and brain damage caused by diseases such as cancer, Alzheimer’s and the Zika virus.

“We show students what a healthy brain looks like, and then a sick brain, like this one with cysticercosis, which causes convulsions,” she says, pointing to a brain stained with marks left by invading tapeworms.

The parasites are present in pork and can also be transmitted when people fail to wash their hands properly, she explains.

Offering more food for thought, she points to another sick brain affected by arteriosclerosis — the result of eating too much fatty food, which clogs the arteries, including the ones feeding the brain.

“This is to remind us not to get carried away with the hamburgers. It’s not good to abuse fatty foods,” she says, pointing out the brain’s blackened blood vessels.

Speaking of food, she warns that visitors need a strong stomach for some parts of the exhibit, such as a display on encephalocele.

The fatal birth defect happens when the “neural tube” that becomes the brain and spinal cord fails to develop normally during pregnancy, leaving the brain and the membranes around it hanging out through an opening in the baby’s skull.

“Around five percent of students are afraid when they see it. Some faint, others vomit,” Rivas says matter-of-factly.

The Nuremberg trials have inspired filmmakers before, from Stanley Kramer’s 1961 drama to the 2000 television miniseries with Alec Baldwin and Brian Cox. But for the latest take, Nuremberg, writer-director James Vanderbilt focuses on a lesser-known figure: The US Army psychiatrist Douglas Kelley, who after the war was assigned to supervise and evaluate captured Nazi leaders to ensure they were fit for trial (and also keep them alive). But his is a name that had been largely forgotten: He wasn’t even a character in the miniseries. Kelley, portrayed in the film by Rami Malek, was an ambitious sort who saw in

Last week gave us the droll little comedy of People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) consul general in Osaka posting a threat on X in response to Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi saying to the Diet that a Chinese attack on Taiwan may be an “existential threat” to Japan. That would allow Japanese Self Defence Forces to respond militarily. The PRC representative then said that if a “filthy neck sticks itself in uninvited, we will cut it off without a moment’s hesitation. Are you prepared for that?” This was widely, and probably deliberately, construed as a threat to behead Takaichi, though it

Among the Nazis who were prosecuted during the Nuremberg trials in 1945 and 1946 was Hitler’s second-in-command, Hermann Goring. Less widely known, though, is the involvement of the US psychiatrist Douglas Kelley, who spent more than 80 hours interviewing and assessing Goring and 21 other Nazi officials prior to the trials. As described in Jack El-Hai’s 2013 book The Nazi and the Psychiatrist, Kelley was charmed by Goring but also haunted by his own conclusion that the Nazis’ atrocities were not specific to that time and place or to those people: they could in fact happen anywhere. He was ultimately

Nov. 17 to Nov. 23 When Kanori Ino surveyed Taipei’s Indigenous settlements in 1896, he found a culture that was fading. Although there was still a “clear line of distinction” between the Ketagalan people and the neighboring Han settlers that had been arriving over the previous 200 years, the former had largely adopted the customs and language of the latter. “Fortunately, some elders still remember their past customs and language. But if we do not hurry and record them now, future researchers will have nothing left but to weep amid the ruins of Indigenous settlements,” he wrote in the Journal of