Every morning at 9am, the intersection of 86th and 40th streets in Mandalay is awakened by the clanging of jade bangles. Traders and brokers in longyis — checkered cloth wrapped around the waist to keep cool in the Myanmar heat — haggle with customers. They pull out large wads of cash amounting to hundreds of thousands of kyat (tens of thousands of New Taiwan Dollars), from their gunny sacks to make transactions. On the ground are cigarette butts, longan shells and maroon-colored stains — the result of chewing and spitting betel nut.

“Jingling the bangles helps to tell if the jade is real or fake,” says La Min May, whose grandfather, U Tin Oo (not to be confused with General Tin Oo), founded the Mandalay Jade Market in 1980. If there’s a sharp sound, chances are it’s real, good quality jade. Another way to tell is to use a flashlight to search for cracks and spots. More cracks mean lower value — useful knowledge to have if I ever land enough money to buy jade.

FEMALE-DOMINATED BUSINESS

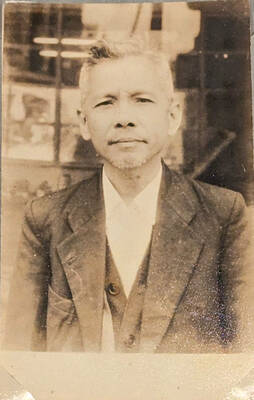

Photo: Dana Ter, Taipei Times

While the men toil and haggle, it’s Myanmar’s women who control the jade industry.

La Min May’s family owns a jewelry shop named after her, and she plans to take over the family business, now run by her mother, Daw Swe Swe Yu, upon graduation.

“I want to be a business woman, and you can most easily earn money in the jade business,” says the 21-year old college student.

Photo: Dana Ter, Taipei Times

Last month, Aung San Suu Kyi’s government passed a moratorium on jade mining permits in northern Myanmar’s resource-rich Kachin state. The decision to freeze renewals of existing permits and suspend the licensing of new ones is due to a couple of reasons: the environmental harm caused by mining, exploitative work conditions and widespread corruption. A report published by Global Witness last year revealed that numerous jade companies were linked to high-ranking ministers in the former junta who were profiting from the trade.

That being said, jade from previous digs are still allowed to be sold at markets. La Min May tells me that so far, business hasn’t been adversely affected. Around 40,000 people pass through the market each day — a sign that jade sales are still going strong. She says that people are buying more now before prices skyrocket.

When I ask La Min May if she thinks the moratorium will have any long-term effects on the industry, she says she isn’t too worried. She believes the moratorium won’t last too long — the country is too reliant on the jade trade.

Photo: Dana Ter, Taipei Times

Though the market is packed, no one is shoving. We inch our way to the jade grinding and polishing area where workers sit on plastic stools, hunched over machines. Another section sells raw jade — a popular option among Chinese buyers who bring it back to China to cut and sell for a profit. There are also individual stores selling jade pendants and necklaces.

Soft-spoken at first, La Min May comes to life when discussing various types of jade. Jadeite, she says, is the more desirable of the two types of jade, the other being nephrite. Ice-colored jadeite found near Myanmar’s two rivers are among the most valuable.

So far, La Min May has traveled to Thailand, Hong Kong and Macau to attend jade trade shows and she’s bent on finding ways to expand her family business overseas.

Photo: Dana Ter, Taipei Times

ALL IN THE FAMILY

On another occasion, I meet with Daw Khin Lay Myint, vice chairwoman of the Gems & Jewelry Entrepreneurs Association at her gems wholesale shop, Thazin Pann, which is now run by her daughter, Su Mon Toe.

Khin Lay Myint is adorned in jade — earrings, bangles and several pendants affixed to her blouse. Her shop — with jade tea sets and jewelry made from jade, sapphires and rubies stacked in shelves and display cabinets — is a far cry from the jade market which her brokers frequent.

Photo: Dana Ter, Taipei Times

Like La Min May, Khin Lay Myint isn’t too concerned about the moratorium. Jade is an integral part of Myanmar’s history, she says, and her family’s history, too.

The business has been in her family for 120 years. The shop didn’t have a name when it was founded by her great-great grandmother. It was common back then for businesses to be known by the name of the person who ran it.

“It’s very different than in Western culture, where it’s all about naming and building your brand,” says Khin Lay Myint.

Photo: Dana Ter, Taipei Times

Knowledge of her family’s business spread through word of mouth, and they gradually built a reputation as a gems wholesaler that offered fair prices.

It wasn’t until Khin Lay Myint opened a hotel five years ago, that she also had to register her gems business (the shop sits on the ground floor of the hotel). She went to a monk who bestowed the name, Thazin Pann — after the thazin orchid. It’s a tradition, she says, going to Buddhist monks for help with naming everything from your children to your company.

Even today, Thazin Pann does not rely on advertising or social media. Khin Lay Myint prefers letting people come to her, and these days, most customers are Chinese who believe that jade is auspicious.

“If a lot of customers come to your store, that means that you are doing something right, as everything is built upon relationships and trust,” she says.

GEMS ARE A GIRL’S BEST FRIEND

A fifteen-minute walk from Thazin Pann is Belgium Star Gems & Jewelry. Facing Mandalay Palace, the jewelry store is a sight to behold in itself: rows of brightly-lit glass cabinets display multi-colored diamonds, emeralds and of course, jade.

Though Belgium Star has been in operation for five years, co-founder Daw Myint Myint Aye’s fascination with rare gems started over two decades ago, when she bought and sold jade as a hobby.

“I feel most happy when I’m holding a lot of gemstones in my hand,” Myint Myint Aye quips.

Behind the jewelry shop are workshops where workers grind and shape jade pieces. She and her 17-year-old daughter take me on a tour while she explains the importance of building a brand name.

Although the gems are from Myanmar, Myint Myint Aye thought of the name Belgium Star to evoke a sense of prestige, as Belgium is home to some of the world’s best diamonds.

“It’s telling customers that we only sell the best,” she says.

Needless to say, the clientele is mostly from Myanmar’s upper class. They buy jade for various reasons: as an investment, because they think it looks pretty or for social status.

But Myint Myint Aye points out that gems are also worn by those who believe that it’ll bring them good luck. In the past, rings with nine colors were worn by men in the army who thought it would protect them on the battlefield. Even today, there’s a belief that if you wore jewelry with both diamonds and emeralds, your business will thrive.

Myint Myint Aye says that although jade prices will increase, she thinks this will only spur customers to buy more, at least in the short term.

“If something is more expensive, it’s perceived to be rare. People love to be in possession of rare items,” she adds.

Looking into the long-term, Myint Myint Aye says that it’s harder to say, though much will be determined by the government’s jade policies.

Her daughter, Tissan, chimes in: “Gems are my mom’s passion.”

When I ask Tissan if she’s keen on taking over the family business, she shakes her head, smiling. She wants to study overseas.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,

Lines between cop and criminal get murky in Joe Carnahan’s The Rip, a crime thriller set across one foggy Miami night, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Damon and Affleck, of course, are so closely associated with Boston — most recently they produced the 2024 heist movie The Instigators there — that a detour to South Florida puts them, a little awkwardly, in an entirely different movie landscape. This is Miami Vice territory or Elmore Leonard Land, not Southie or The Town. In The Rip, they play Miami narcotics officers who come upon a cartel stash house that Lt. Dane Dumars (Damon)

Jan. 19 to Jan. 25 In 1933, an all-star team of musicians and lyricists began shaping a new sound. The person who brought them together was Chen Chun-yu (陳君玉), head of Columbia Records’ arts department. Tasked with creating Taiwanese “pop music,” they released hit after hit that year, with Chen contributing lyrics to several of the songs himself. Many figures from that group, including composer Teng Yu-hsien (鄧雨賢), vocalist Chun-chun (純純, Sun-sun in Taiwanese) and lyricist Lee Lin-chiu (李臨秋) remain well-known today, particularly for the famous classic Longing for the Spring Breeze (望春風). Chen, however, is not a name