Taiwan in Time: July 25 to July 31

In late July of 1914, a fierce, two-month battle was nearing its end in the mountains of present-day Hualien County (花蓮).

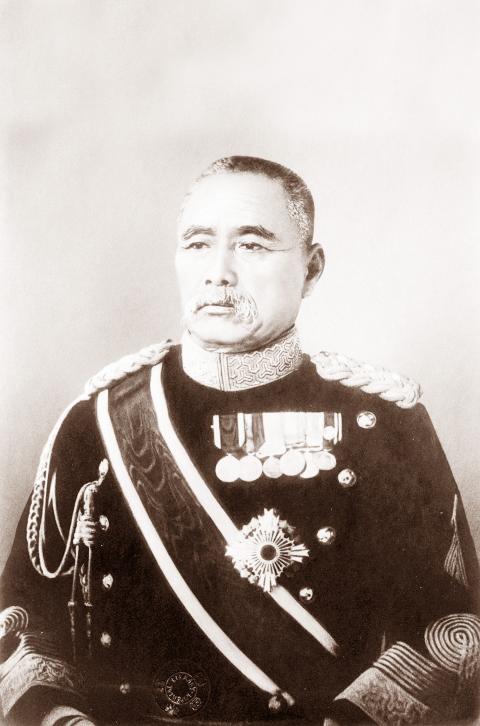

Sakuma Samata, then-governor general of Taiwan who personally participated in the battle, had fallen off a cliff a month earlier and was in critical condition — but the outcome was already decided, as the main resistance had surrendered and given up their weapons a few weeks earlier.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Soon, the Japanese would finally effectively control Taiwan in its entirety, the process taking more than two decades as it spent the first decade dealing with armed Han uprisings.

With more than 10,000 men on the Japanese side, this would be the largest and final battle of Sakuma’s Aboriginal pacification campaign.

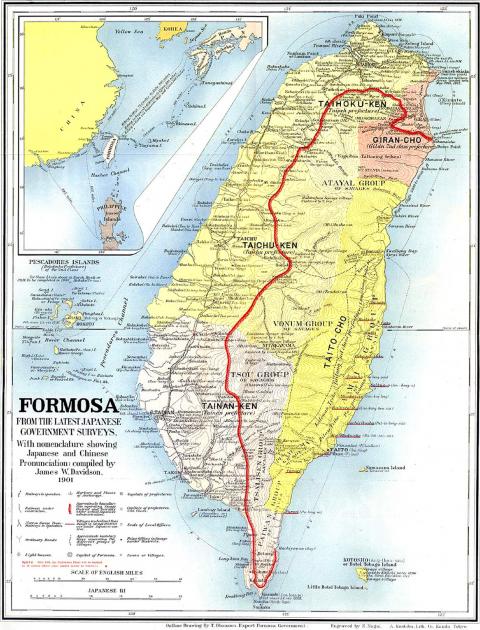

The Japanese took over Taiwan in 1895, but up until 1910, they still were not able to entirely control the mountainous Aboriginal areas. The government mostly isolated the Aborigines in the mountains with “guard lines,” which consisted of wooden or electric fences (and sometimes landmines) with guard stations. These lines were originally defensive in nature, but eventually they became a means of cutting off and encircling the tribes as they were built deeper and deeper into Aboriginal territory.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The Truku had caused the colonial government trouble as early as 1896 and was reportedly one of the fiercest tribes to resist Japanese rule. The last major incident took place just four months after Sakuma took office in August 1906, when about 30 Japanese were killed, including the governor of Karenko Subprefecture (the eastern part of today’s Hualien County).

Sakuma had dealt with the Aborigines as early as 1874 during the Mudan Incident, when Japan sent a punitive expedition to punish Paiwan tribesmen who had killed 54 shipwrecked Ryukuan sailors. He reportedly earned the epithet “Demon Sakuma” due to his fierceness during this battle and was the one who killed the Mudan Village chief.

In 1907, Sakuma announced his first five-year plan to “govern the savages.” For the Aborigines in the Truku area, this entailed setting up new guard lines in the mountains to further isolate the tribes, and then finally subjugating them through military action if necessary. He also had ships patrol the coast to cut them off from the other side.

Some Aborigines surrendered and allowed the enclosures, either intimidated by force or enticed by governmental promises — but others decided to fight, leading to several bloody incidents. Sakuma decided that a new direction was needed.

In 1910, he received massive funding from the Japanese government for a new five-year plan, taking on a more aggressive, militaristic approach with armed police, especially in the northern part of Taiwan. They continued to push the guard lines forward, with a major goal of confiscating the weapons of the Aborigines, leaving them with no means to resist. Most estimates show that more than 20,000 guns were collected during this time.

There were several groups that were classified as “vicious savages,” and therefore, Sakuma required military expeditions. After campaigns against other tribes in 1910, 1911 and 1913, Sakuma saved the Truku for last.

Starting from 1913, Sakuma sent scouts to survey the Truku terrain, and also trained Truku language translators. In late May of 1914, the 69-year-old personally led more than 10,000 police, soldiers and other personnel toward Truku territory. Most records show that the Truku had at most 3,000 fighting men.

This was not a straight-up extermination campaign, as the troops promised the Aborigines they wouldn’t be harmed if they handed over all their guns and ammunition — and many did so. After two months of battle, the fighting gradually resided and the official surrender ceremony was held on Aug. 13.

At the end of the war, the Japanese had only lost about 150 men, of which 76 were killed in battle, according to official numbers from the Governor-General’s Office. There are no numbers on how many Aborigines were killed.

Afterward, the Japanese sent personnel in to the mountains to build roads and bridges, set up telephone wires as well as round up the remaining ammunition and people who went into hiding. They also built police and patrol facilities and stationed troops in the area.

Sakuma recovered from his injuries and headed back to Japan in September to report to the emperor the completion of his mission. He remained as governor-general until April 1915.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

This is the year that the demographic crisis will begin to impact people’s lives. This will create pressures on treatment and hiring of foreigners. Regardless of whatever technological breakthroughs happen, the real value will come from digesting and productively applying existing technologies in new and creative ways. INTRODUCING BASIC SERVICES BREAKDOWNS At some point soon, we will begin to witness a breakdown in basic services. Initially, it will be limited and sporadic, but the frequency and newsworthiness of the incidents will only continue to accelerate dramatically in the coming years. Here in central Taiwan, many basic services are severely understaffed, and

Jan. 5 to Jan. 11 Of the more than 3,000km of sugar railway that once criss-crossed central and southern Taiwan, just 16.1km remain in operation today. By the time Dafydd Fell began photographing the network in earnest in 1994, it was already well past its heyday. The system had been significantly cut back, leaving behind abandoned stations, rusting rolling stock and crumbling facilities. This reduction continued during the five years of his documentation, adding urgency to his task. As passenger services had already ceased by then, Fell had to wait for the sugarcane harvest season each year, which typically ran from

It is a soulful folk song, filled with feeling and history: A love-stricken young man tells God about his hopes and dreams of happiness. Generations of Uighurs, the Turkic ethnic minority in China’s Xinjiang region, have played it at parties and weddings. But today, if they download it, play it or share it online, they risk ending up in prison. Besh pede, a popular Uighur folk ballad, is among dozens of Uighur-language songs that have been deemed “problematic” by Xinjiang authorities, according to a recording of a meeting held by police and other local officials in the historic city of Kashgar in

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) was out in force in the Taiwan Strait this week, threatening Taiwan with live-fire exercises, aircraft incursions and tedious claims to ownership. The reaction to the PRC’s blockade and decapitation strike exercises offer numerous lessons, if only we are willing to be taught. Reading the commentary on PRC behavior is like reading Bible interpretation across a range of Christian denominations: the text is recast to mean what the interpreter wants it to mean. Many PRC believers contended that the drills, obviously scheduled in advance, were aimed at the recent arms offer to Taiwan by the