Taiwan in Time: May 16 to May 22

On April 20, 1949, negotiations broke down between the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Chinese Communist Party, as the People’s Liberation Army continued its offensive, capturing the Nationalist capital of Nanjing three days later and then continuing to push southward.

Chen Cheng (陳誠), who had been sent to govern Taiwan five months before the offensive, was worried that Communists would try to sneak their way into Taiwan amid the mass Nationalist retreat across the Taiwan Strait, writes historian Chen Shih-chang (陳世昌) in his book, Taiwanese History, 70 Years After the War (戰後70年台灣史).

Courtesy of Google

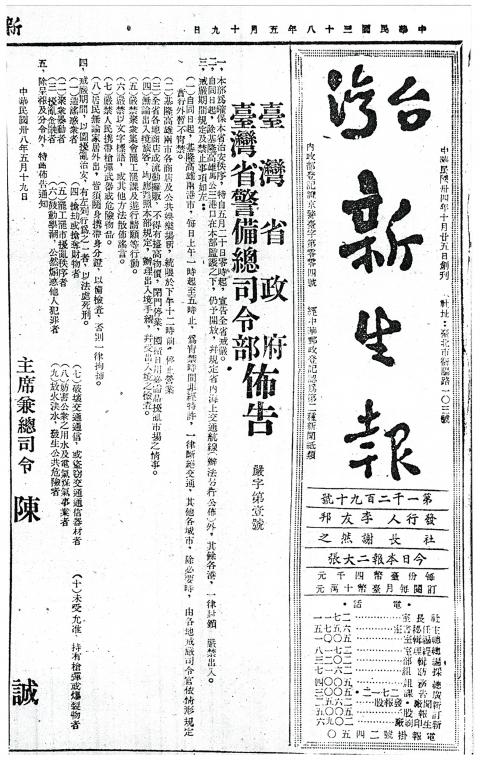

On May 19, Chen Cheng declared martial law, to take effect at midnight the next day.

Chen Shih-chang writes in his memoir that martial law provisions made it easier for him to enact laws to restrict people entering and exiting Taiwan — the main purpose being to weed out possible communists. He was likely also responding to unrest within Taiwan, such as the student protests against police brutality that led to the April 6 Incident when military and police personnel stormed National Taiwan Normal University dorms and arrested about 200 students.

Some dispute the legality of this move, claiming that Chen Cheng had no right to declare martial law as, according to Article 39 of the Republic of China constitution, only the president had the power to do so and it had to be subsequently approved by the Legislative Yuan. Chen Cheng, however, claims in his memoir that he was acting under direct orders from the central government.

Photo: Tsai Chih-ming, Taipei Times

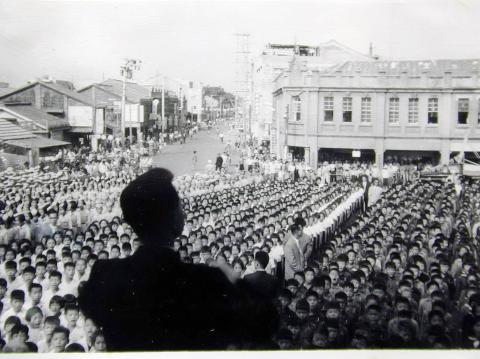

No matter what Chen Cheng’s intentions were, or whether it was legal or not, his declaration would remain in place for the next 38 years and 56 days — one of the longest duration of martial law in the modern era.

The real ramifications were that after the KMT’s full retreat to Taiwan, they would use it to keep Taiwan in a constant state of emergency and, combined with other laws, they exercised authoritarian control over the government and people.

It was the second time martial law had been declared in Taiwan. The first one was issued in 1947 by governor-general Chen Yi (陳儀) the day the 228 Incident broke out, and curfews were imposed in Taipei and Keelung. Chen lifted it the next day, only to declare it again on March 8 as the situation worsened and government troops clashed with civilians. Meanwhile, the commander in Hsinchu made his own declaration on March 4.

Photo: Wu Hsing-hua, Taipei Times

This period was short-lived. On May 16, Wei Dao-ming (魏道明) arrived to replace Chen Yi, and one of his first acts was to lift martial law and stop the government’s qingxiang (清鄉, the countrywide arresting or killing of civilians suspected to have ties to the uprising).

KMT leader Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) declared martial law in December 1948 as the civil war worsened — but this issuance excluded non-war zones such as Tibet (which the KMT had no control over anyway), Qinghai and Taiwan.

Chen Cheng’s initial declaration closed all ports except for Keelung, Kaohsiung and Makung, established curfews for civilians and businesses, forbade merchants from raising prices or stocking up on goods for personal use and prohibited public gatherings, strikes, protests, bearing arms and “spreading rumors.” All citizens were required to have identification on them at all times, or face arrest.

Later that month, the Punishment of Rebellion Act (懲治叛亂條例) was enacted, which called for automatic death sentences for internal rebels or traitors to the country. The act specified that all trials be carried out by military tribunals regardless of the subject’s identity. Originally aimed towards Communist collaborators, the KMT would later use the act, along with the Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of Communist Rebellion (動員戡亂時期臨時條款), to suppress freedom of speech, ban opposition parties and arrest suspected independence activists and other dissidents.

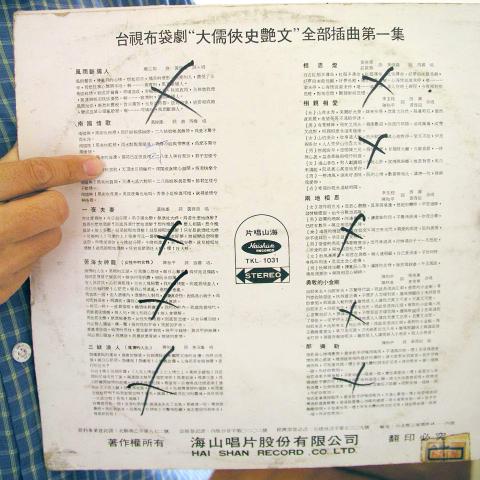

Finally, provisions were enacted allowing government screening and censorship of all publications, recordings and performances. Restrictions included defaming government leaders, promoting communism, swaying civilian loyalty toward government and disrupting social security — but in reality the scope was much wider, including sexually-explicit content and even martial arts novels.

With that, all conditions were ripe for the height of the White Terror era.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Many people noticed the flood of pro-China propaganda across a number of venues in recent weeks that looks like a coordinated assault on US Taiwan policy. It does look like an effort intended to influence the US before the meeting between US President Donald Trump and Chinese dictator Xi Jinping (習近平) over the weekend. Jennifer Kavanagh’s piece in the New York Times in September appears to be the opening strike of the current campaign. She followed up last week in the Lowy Interpreter, blaming the US for causing the PRC to escalate in the Philippines and Taiwan, saying that as

US President Donald Trump may have hoped for an impromptu talk with his old friend Kim Jong-un during a recent trip to Asia, but analysts say the increasingly emboldened North Korean despot had few good reasons to join the photo-op. Trump sent repeated overtures to Kim during his barnstorming tour of Asia, saying he was “100 percent” open to a meeting and even bucking decades of US policy by conceding that North Korea was “sort of a nuclear power.” But Pyongyang kept mum on the invitation, instead firing off missiles and sending its foreign minister to Russia and Belarus, with whom it

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has a dystopian, radical and dangerous conception of itself. Few are aware of this very fundamental difference between how they view power and how the rest of the world does. Even those of us who have lived in China sometimes fall back into the trap of viewing it through the lens of the power relationships common throughout the rest of the world, instead of understanding the CCP as it conceives of itself. Broadly speaking, the concepts of the people, race, culture, civilization, nation, government and religion are separate, though often overlapping and intertwined. A government

Nov. 3 to Nov. 9 In 1925, 18-year-old Huang Chin-chuan (黃金川) penned the following words: “When will the day of women’s equal rights arrive, so that my talents won’t drift away in the eastern stream?” These were the closing lines to her poem “Female Student” (女學生), which expressed her unwillingness to be confined to traditional female roles and her desire to study and explore the world. Born to a wealthy family on Nov. 5, 1907, Huang was able to study in Japan — a rare privilege for women in her time — and even made a name for herself in the