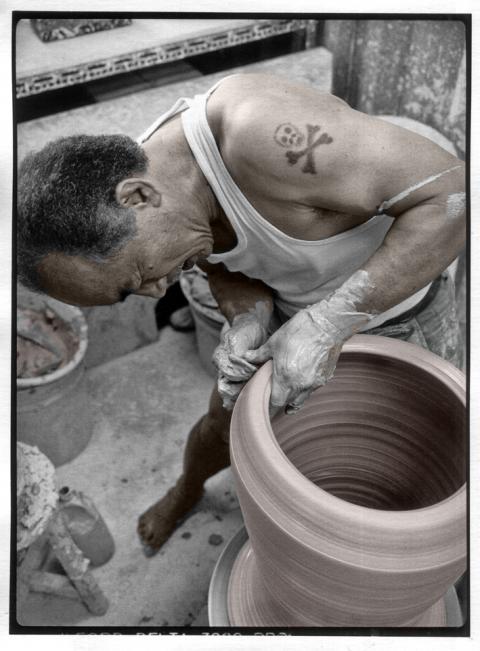

Kick-wheel potter Chan Kuo-hsiang (詹國祥) tells a story of how late president Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國) was puzzled during a visit to the old pottery town of Yingge (鶯歌鎮). BMWs and Mercedes were parked along streets lined with dilapidated buildings — conspicuous wealth amid ramshackle abodes.

Before China opened up its market, Yingge potters producing imitation Chinese ceramics were raking it in.

“The heyday was probably 1980 to 1990,” says Cheng Wen-hung (程文宏), head of the Educational Promotion Department of the New Taipei City Yingge Ceramics Museum. “After that... most of the big factories moved to China.”

Photo: Paul Cooper, Taipei Times

Chan and his brother, Weng Kuo-hua (翁國華), specialize in throwing huge pots. They have seen good times and bad. In many ways, their fortunes have been tied to those of Yingge itself.

Yingge has been a pottery town since 1804. It flourished because of local coal and clay deposits, and, later, because the arrival in Taiwan of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in 1949 put a temporary stop to pottery imports from Japan and China. This gave Yingge potters the chance to start producing functional wares for the domestic market.

IMITATING DYNASTIC PORCELAIN

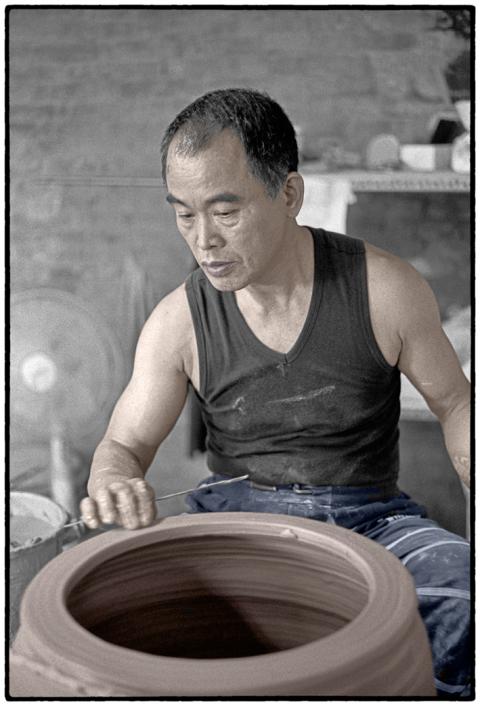

Photo: Paul Cooper, Taipei Times

In the 1970s, many factories also started producing imitation Chinese imperial wares. Experts from Hong Kong were brought over to introduce traditional Chinese ceramics techniques. Many of the wares were exported, and some were sold as authentic Song, Yuan, Ming and Qing porcelains.

For a time, there was money to be made, with imitation wares being sent to Hong Kong, Japan and the West. Yingge had moved from its humble beginnings to become a major exporter of quality wares.

Chan and Weng were born in Yingge, but their father, a kick-wheel potter making large water jars in the town, moved the family to Miaoli in search of work when they were still little. The family was too poor to afford rent. The boss was kind enough to let the whole family live in the factory. The brothers lived there until they were 20.

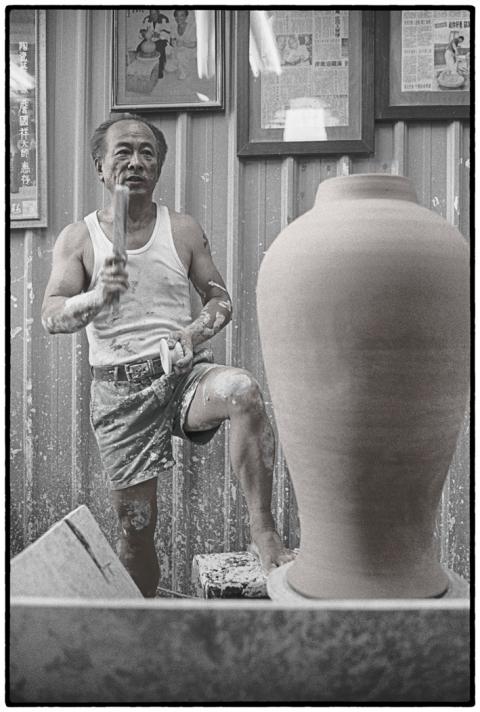

Photo: Paul Cooper, Taipei Times

Being constantly around the factory for their entire childhood, the brothers were able to learn their craft — learning the techniques of coiling and throwing on the kick-wheel, the traditional potters’ wheel introduced by the Japanese and used in Taiwan before the invention of an electric version.

Weng started learning properly when he was around nine or 10, working at the factory at around 16 or 17.

“I was very skilled at this point, since I had started very early.” he remembers.

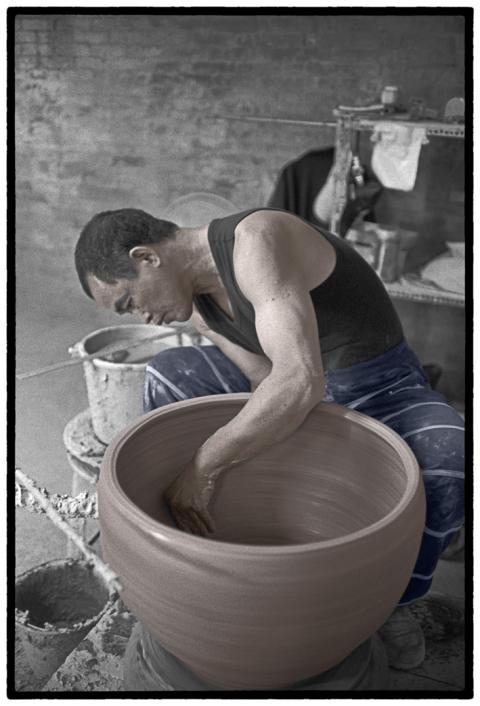

Photo: Paul Cooper, Taipei Times

During the heyday, Weng took off on his own and developed his own crystal glaze over many years of experimentation. He would decorate his own pots with this glaze, and sell them in shops around Yingge.

“It would cost me NT$50,000 to make one piece. The shop would place a heavy commission on top of this, charging say NT$300,000,” Weng says.

Weng remembers turning his own house into a factory, to fit in all the large kilns he needed, and having no space left in which to sleep.

Photo courtesy of Chan Kuo-hsiang

“I was nuts. I spent all my money on the kilns and on making the pots,” says Weng. “I could have bought a lot of houses for that money.”

MARKET CHANGE

Then the market changed. Cheng says that increased investment in China led to a steep decline in the number of people employed at factories in Taiwan. Only a few people work in the factories producing imitation wares nowadays.

Weng had to abandon his creative work in 1996. He drove a truck, delivering electrical goods around Taiwan, from ages 43 to 53. He returned to Yingge 10 years ago to work in a factory again.

You won’t see so many luxury cars in Yingge nowadays. Much of the creative work has moved out of town, where people work in smaller studios.

Chan has his own factory now, making large pots to order. He also introduces the kick wheel technique every week at the museum, hoping to keep the tradition alive.

Weng works in a factory. He still coils water jars. He has plans of making more creative work again, resurrecting his crystal glaze. Unlike his brother, he is not very positive about the possibility of passing on their traditions.

“There is a good reason the younger generation don’t want to do this kind of work, not if they don’t come from a rich family. There’s simply no money in doing it at a creative level,” Weng says.

Next month, Tseng Tsai-wan (曾財萬), also known as Master Wan, who shows that locally-produced quality wares still have a place in a fiercely competitive market.

Yingge Town Artisan is a monthly photographic and historical exploration of the artists and potters linked to New Taipei City’s Yingge Town.

Last week the story of the giant illegal crater dug in Kaohsiung’s Meinong District (美濃) emerged into the public consciousness. The site was used for sand and gravel extraction, and then filled with construction waste. Locals referred to it sardonically as the “Meinong Grand Canyon,” according to media reports, because it was 2 hectares in length and 10 meters deep. The land involved included both state-owned and local farm land. Local media said that the site had generated NT$300 million in profits, against fines of a few million and the loss of some excavators. OFFICIAL CORRUPTION? The site had been seized

Next week, candidates will officially register to run for chair of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). By the end of Friday, we will know who has registered for the Oct. 18 election. The number of declared candidates has been fluctuating daily. Some candidates registering may be disqualified, so the final list may be in flux for weeks. The list of likely candidates ranges from deep blue to deeper blue to deepest blue, bordering on red (pro-Chinese Communist Party, CCP). Unless current Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) can be convinced to run for re-election, the party looks likely to shift towards more hardline

Sept. 15 to Sept. 21 A Bhutanese princess caught at Taoyuan Airport with 22 rhino horns — worth about NT$31 million today — might have been just another curious front-page story. But the Sept. 17, 1993 incident came at a sensitive moment. Taiwan, dubbed “Die-wan” by the British conservationist group Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), was under international fire for being a major hub for rhino horn. Just 10 days earlier, US secretary of the interior Bruce Babbitt had recommended sanctions against Taiwan for its “failure to end its participation in rhinoceros horn trade.” Even though Taiwan had restricted imports since 1985 and enacted

The depressing numbers continue to pile up, like casualty lists after a lost battle. This week, after the government announced the 19th straight month of population decline, the Ministry of the Interior said that Taiwan is expected to lose 6.67 million workers in two waves of retirement over the next 15 years. According to the Ministry of Labor (MOL), Taiwan has a workforce of 11.6 million (as of July). The over-15 population was 20.244 million last year. EARLY RETIREMENT Early retirement is going to make these waves a tsunami. According to the Directorate General of Budget Accounting and Statistics (DGBAS), the