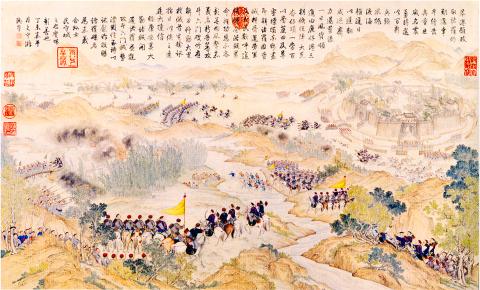

Taiwan in Time: April 18 to April 24

It had been a year since Lin Shuang-wen (林爽文) and his Heaven and Earth Society (天地會) brethren attacked a government troop camp, igniting the largest rebellion under Qing Dynasty-ruled Taiwan.

The Qianlong emperor had sent reinforcements earlier, but they made little progress, shifting into a defensive stance, especially as Lin’s troops had surrounded Chuluo (諸羅, today’s Chiayi) for the previous six months, relentlessly trying to recapture the city they had lost.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Finally, the emperor sent one of his favorite officials and military commanders, Fukangan (福康安), across the strait, bringing with him more than 120 elite baturu, Manchu and Mongol warriors, and 9,000 specially chosen soldiers from across China.

Their orders: end the siege of Chuluo and capture Lin alive and bring him back to Beijing.

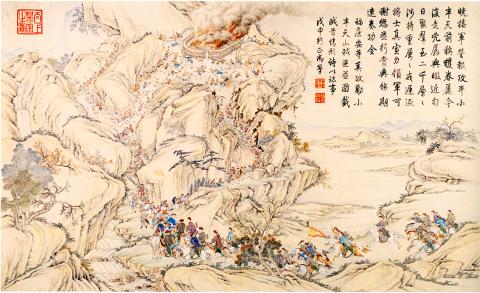

It had been 66 years since the Qing Dynasty sent troops across the Taiwan Strait to quell a rebellion by “Duck King” (鴨母王) Chu Yi-kuei (朱一貴), a man who shared a surname with the Ming Dynasty royal house and, it was said, rose up due to civilian mistreatment by local officials. Chu, a duck farmer from what is today Kaohsiung, drove out local Qing troops and declared himself Ming Emperor — ruling over today’s Kaohsiung, Tainan and Chiayi.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

His empire lasted two months — it is said they did not even have time to make Ming-style court clothing and instead borrowed from performance troupes — as reinforcements from China decimated his troops within two weeks of their arrival.

Lin’s rebellion, in contrast, took over a year to pacify. Liu Ni-ling (劉妮玲) writes in her Study of Civil Uprisings in Taiwan During the Qing Dynasty (清代台灣民變研究) that it cost the Qing the most troops and money.

Back then, the Qing Dynasty paid little attention to Taiwan, which it had considered its territory since 1683. It sent officials and troops, but was unwilling to actively develop the area.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

ISLAND OF REBELLIONS

One of these officials, Yao Ying (姚瑩), once said that Taiwan was plagued by “bandits, armed conflict [between various Han Chinese groups] and rebellion.” Many sources claim that most of the officials were incompetent and corrupt as well, contributing to a vicious cycle. Liu counts a total of 73 uprisings during roughly 200 years of Qing rule — about 20 of them taking place before Lin’s.

Despite migration restrictions, many people illegally made the cross-strait journey to seek a better living. Lin was one of them, arriving with his father in 1773 from Fujian Province.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Many arrivals could not find land to farm, often becoming wandering bandits or other criminals. Fukangan says in the official Qing account of the rebellion that much of Lin’s army consisted of these people.

In 1784, Lin became the leader of the local Heaven and Earth Society (天地會), which was rumored to have been started by Ming loyalist Cheng Cheng-kung (鄭成功), also known as Koxinga, who drove the Dutch out of Taiwan in the 1600s.

Liu writes that by Lin’s time, such societies had lost their original anti-Qing purpose and became a way for people to unite and protect each other in a lawless society where armed conflict and blood feuds were common. However, they also served as muscle for people to attack other groups.

The incident began, Liu writes, with a seemingly unrelated dispute between two brothers which, as was common in those days, erupted into armed conflict. After the government arrested the brothers, it started hunting down those involved — many of which sought out Lin’s society for protection.

ROOTING OUT THE ‘BANDITS’

Officials had been wary of Lin’s influence before, but now they had an excuse to investigate and they began actively arresting and executing Heaven and Earth Society members. The troops eventually entered Lin’s territory of Changhua to find him, allegedly burning down entire villages that did not comply.

Lin’s comrades decided to fight back, and asked him to come out of hiding. They won the first battle, destroying the government camp and capturing Changhua’s county seat.

By the time they turned toward Chuluo a week later, their forces numbered in the tens of thousands. Their actions caused a chain reaction as leaders in other localities also took up arms, such as Chuang Ta-tian (莊大田) who captured Fengshan (鳳山).

Despite their success, Liu writes that the rebels lacked a clear purpose and organizational structure.

“The rebellion was not out of ethnic [or national] interest, and there was little desire for the rebels to pursue political power,” she writes. “They appeared to be anti-Qing, but in reality they were more against government officials, and caused more social strife than political chaos.”

The rebels’ success was short-lived, as Qing troops, aided by yimin (義民, righteous citizens) — locals who helped fight the rebels to protect their own interests — held on to the government seat of Tainan.

Liu writes that these yimin helped reconquer Changhua twice and played a significant role in keeping the rebels at bay during the siege of Chuluo. As a reward, the Qianlong Emperor gave Chuluo the name “Chiayi” (literally: commendable righteousness). However, Liu writes that many yimin also took the opportunity to loot and pillage.

Liu adds that historical tensions and infighting between ethnic groups also impeded the rebels’ efforts. Reinforcements from China quickly retook Fengshan and Chuluo — but they were unable to make any more progress as Chuang captured Fengshan for the second time and Lin relentlessly besieged Chuluo.

Things finally changed when Fukangan arrived. In just a month, he and his troops ended things, and Lin was taken to Beijing, tried and executed.

The Qianlong emperor would later list this battle as one of his “10 great campaigns” — not bad for a little island the government did not care about.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Lines between cop and criminal get murky in Joe Carnahan’s The Rip, a crime thriller set across one foggy Miami night, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Damon and Affleck, of course, are so closely associated with Boston — most recently they produced the 2024 heist movie The Instigators there — that a detour to South Florida puts them, a little awkwardly, in an entirely different movie landscape. This is Miami Vice territory or Elmore Leonard Land, not Southie or The Town. In The Rip, they play Miami narcotics officers who come upon a cartel stash house that Lt. Dane Dumars (Damon)

Today Taiwanese accept as legitimate government control of many aspects of land use. That legitimacy hides in plain sight the way the system of authoritarian land grabs that favored big firms in the developmentalist era has given way to a government land grab system that favors big developers in the modern democratic era. Articles 142 and 143 of the Republic of China (ROC) Constitution form the basis of that control. They incorporate the thinking of Sun Yat-sen (孫逸仙) in considering the problems of land in China. Article 143 states: “All land within the territory of the Republic of China shall