Taiwan in Time: Oct. 26 to Nov. 1

Awi Hepah thought it was just a Japanese fighter plane carrying out a routine bombing mission against his Aboriginal Sediq people in the mountains of what is today Nantou County (南投). After all, they were at war with the Japanese police and army.

“We smelled something strange,” he recalls in the book Awi Hepah’s Personal Testimony (阿威赫拔的親身證言). “At the same time, everyone felt like vomiting, and our visions blurred. Some couldn’t stand straight and went looking for water. Some started coughing blood, and others were in so much pain that they were pounding their chests. Some were in so much pain that they dropped their guns and hung themselves.”

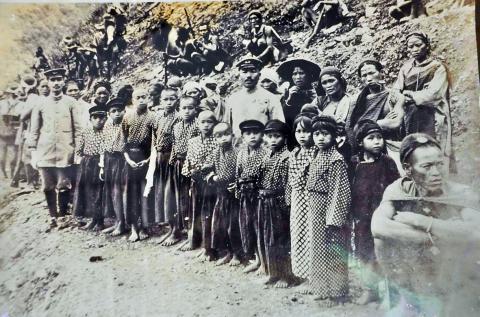

Photo: Chen Fong-li

A few days later, it happened again as the warriors hid in a cave.

“My companions died one after another,” he writes. “Their faces were grotesquely twisted, their skin rotting and giving off a putrid smell.”

Only 14 years old at the time, Hepah was an active participant in the Wushe Incident (霧社事件), where hundreds of Sediq warriors, after years of colonial mistreatment, attacked and killed 134 Japanese (and accidentally two Han Chinese in Japanese clothing) in the morning of Oct. 27, 1930.

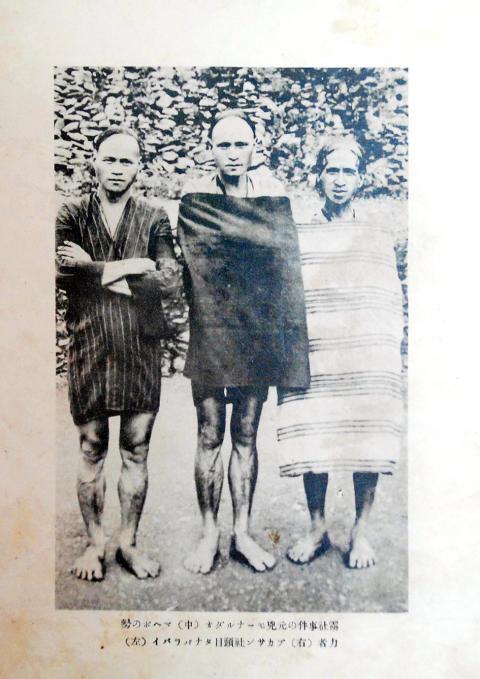

Photo provided by Chen Shui-mu

Public awareness of the incident has exploded since the 2011 hit movie Warriors of the Rainbow: Seediq Bale (賽德克巴萊), but a lesser known fact is that this conflict is possibly the first instance of chemical warfare in Asia.

Chemical warfare was used on a large scale during World War I, where a reported 124,000 tons of chemicals were produced, leading to roughly 90,000 deaths. This led to the passing of the Geneva Protocol in 1925, which banned the use of chemical and biological weapons.

However, Japan and the US didn’t ratify the protocol. Most first mentions of chemical weapons being used in Asia point to the Japanese invasion of China in 1937, but there is evidence, as Hepah’s account suggests, that they were also employed during the Wushe conflict.

Photo: Chen Fong-li

Biological and chemical weapons expert Eric Croddy writes in his Weapons of Mass Destruction encyclopedia that the Japanese had been experimenting with mustard gas as early as 1928, even establishing a chemical weapons factory in northern Taiwan, which was reportedly still present when the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) arrived in 1945.

Let’s revisit the story first.

THE UPRISING

As the Japanese national anthem filled the track field at Wushe’s elementary school the morning of the incident, the people gathered there for an athletic meet had no idea that they were surrounded by hundreds of armed Sediq warriors.

The Japanese were easy to recognize in their native costume, and the warriors charged onto the field, killing all targets they could see.

By that time, the Han Chinese population had already given up armed resistance and turned to nonviolent social and political movements. Aboriginal uprisings became less common into the 1920s, but tensions remained high due to discrimination, forced labor, logging, disrespect of customs and other issues.

The Sediq — classified as Atayal until 2008 — involved in the incident belonged to six tribes within the the Tgadaya subgroup, totaling about 1,200 people. Mona Rudao, who led the uprising, was the chief of one of the tribes.

Most accounts of the incident point to a confrontation between Mona Rudao’s son and a Japanese police officer over the officer’s refusal to accept an offering cup of wine during the son’s wedding ceremony as the final trigger. The officer either struck the cup or the son’s arm with his stick, and a brawl ensued. The tribe’s apology to the officer was not accepted, and rather than wait for official punishment, Mona Rudao channeled years of resentment and called for the surprise attack.

The Japanese retaliated with a force of about 2,000 troops and police officers, but faced stiff resistance despite their superior numbers. Yet, they were able to quell the rebellion in less than two months, with more than 600 Sediq dead. About half of them, including Mona Rudao, committed suicide rather than surrender.

POISON GAS?

Croddy states in several publications that “historians agree” that chloracetophenone, which is used in mace and tear gas, was used against the Sediq.

However, the Wushe entry in his encyclopedia suggests the possibility that a “more deadly form of gas” was used.

Many publications and sources — both English and Chinese — use the term “poison gas,” (毒氣, 毒瓦斯) while others claim that the Japanese used vesicant gases, or blistering agents, and a few specifically say that it was mustard gas or a variation of it.

Awi Hepah insists that it was more than tear gas, and in addition claims that the Japanese were “testing” their weapons on his people. If his accounts of the symptoms hold accurate, the gas bombs indeed seem to contain something more potent.

The final piece of evidence comes from Japanese sources.

A telegram from the commander of the Taiwan army to the Japanese Army Minister, sent on Nov. 3, 1930, contains a request for blistering agents.

A military report made a day earlier states, “Due to concerns that usage of smoke and explosives may be affected due to the terrain, we hope to use chemical means to attack.”

Another telegram, sent on Nov. 8, reports a plan to “use airplanes to test the effects of six gas bombs.” A later report confirms that the attack was carried out, but the “results are unclear.”

There’s no direct mention of the blistering agent being used, but the evidence is compelling.

And according to Croddy, it doesn’t matter what kind of gas was used.

“While (tear gas) usually considered a riot control agent, like any other toxic chemical, it is considered a chemical weapon by the Chemical Weapons Convention when used in warfare,” he says.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Recently the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and its Mini-Me partner in the legislature, the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), have been arguing that construction of chip fabs in the US by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電) is little more than stripping Taiwan of its assets. For example, KMT Deputy Secretary-General Lin Pei-hsiang (林沛祥) in January said that “This is not ‘reciprocal cooperation’ ... but a substantial hollowing out of our country.” Similarly, former TPP Chair Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) contended it constitutes “selling Taiwan out to the United States.” The two pro-China parties are proposing a bill that would limit semiconductor

Institutions signalling a fresh beginning and new spirit often adopt new slogans, symbols and marketing materials, and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) is no exception. Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文), soon after taking office as KMT chair, released a new slogan that plays on the party’s acronym: “Kind Mindfulness Team.” The party recently released a graphic prominently featuring the red, white and blue of the flag with a Chinese slogan “establishing peace, blessings and fortune marching forth” (締造和平,幸福前行). One part of the graphic also features two hands in blue and white grasping olive branches in a stylized shape of Taiwan. Bonus points for

March 9 to March 15 “This land produced no horses,” Qing Dynasty envoy Yu Yung-ho (郁永河) observed when he visited Taiwan in 1697. He didn’t mean that there were no horses at all; it was just difficult to transport them across the sea and raise them in the hot and humid climate. “Although 10,000 soldiers were stationed here, the camps had fewer than 1,000 horses,” Yu added. Starting from the Dutch in the 1600s, each foreign regime brought horses to Taiwan. But they remained rare animals, typically only owned by the government or

“M yeolgong jajangmyeon (anti-communism zhajiangmian, 滅共炸醬麵), let’s all shout together — myeolgong!” a chef at a Chinese restaurant in Dongtan, located about 35km south of Seoul, South Korea, calls out before serving a bowl of Korean-style zhajiangmian —black bean noodles. Diners repeat the phrase before tucking in. This political-themed restaurant, named Myeolgong Banjeom (滅共飯館, “anti-communism restaurant”), is operated by a single person and does not take reservations; therefore long queues form regularly outside, and most customers appear sympathetic to its political theme. Photos of conservative public figures hang on the walls, alongside political slogans and poems written in Chinese characters; South