The desk space next to PCs first welcomed paper printers and later made room for 3D printers that could conjure any shape from spools of plastic.

Now new devices, including laser cutters and computer-controlled milling machines, are coming out of industrial workshops and planting themselves on desktops. The wave of new machines is bringing a new level of precision to people who make physical objects — from leather wallets to lamps to circuit boards — as a career or hobby.

It is part of a familiar theme in tech. Computers help transform expensive, complicated machines used by the few and make them more accessible to the many. The creative types — designers, craftsmen, tinkerers — take it from there.

Photo: REUTERS/Gary Cameron

“Your creativity is no longer limited by tools,” said Dan Shapiro, co-founder and chief executive of Glowforge, a startup in Seattle’s industrial SoDo neighborhood that is developing a laser cutter.

EASY TO USE

Glowforge operates out of a cavernous warehouse, next to a marijuana processing center, where it has created a prototype of a desktop laser cutter that it plans to sell for around US$2,000, much cheaper than comparable machines. Glowforge says the device, which Shapiro calls a 3D laser printer, will come with software that makes it much easier to operate than laser cutters usually are.

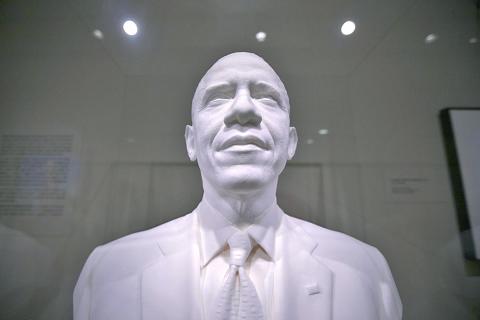

Photo: Bloomberg/Andrew Harrer

Laser cutters have been around for decades, used in industrial manufacturing applications to engrave or slice through almost any material you can think of, including steel, plastic and wood. The computer-controlled lasers in them make precision cuts that would be almost unimaginable by hand, except by highly skilled artisans.

Over the years, the machines have become a bit smaller and more available to ordinary people, largely through so-called makerspaces, open facilities aimed at designers, do-it-yourself enthusiasts and others that are sometimes housed in schools and sometimes privately owned. The machines have developed a strong following among jewelry-makers, printmakers and other artisans, many of whom have hung shingles out on craft sites like Etsy.

In fact, makerspaces report that they are often overwhelmed with demand for their laser cutters and see far less use of 3D printers, which are slow, more limited in the materials they can work with and sometimes fiendishly hard to operate.

Photo: AFP/Yoshikazu Tsuno

Nadeem Mazen, chief executive of DangerAwesome, a makerspace in Cambridge, Massachusetts, says his facility’s three laser cutters do 20 to 30 times more business than his two 3D printers.

“That laser cutter is going all the time,” said Chris DiBona, an engineering director at Google, describing the makerspace at his daughter’s school.

Laser cutters are so fast, he said, it was easy to produce an object, tweak its design and create something new.

Photo: Bloomberg/Akio Kon

DiBona is a personal investor in Glowforge, though Google is not. The startup has raised more than US$1 million.

Shapiro, who used to work at Google and Microsoft, says he is determined to make laser cutters much more accessible. Good ones typically cost around US$10,000, though it’s possible to find cheaper laser cutters online from China that Shapiro says lack adequate cutting power and safety features.

To cut costs, Glowforge has found ways to substitute sophisticated software for expensive hardware components. A camera inside the laser-cutting chamber and image processing in the cloud will take the place of a part called a motion planner that normally determines how the laser cuts material.

Mazen said he had been searching for a device like the Glowforge, which he hadn’t heard of, without success.

“In my experience,” he said, “not only would this be eminently useful, it’s the primary thing I’m looking for now.”

To demonstrate the creative possibilities of the Glowforge, Shapiro last week whipped out his wallet, a handsome leather case with hand stitching around the seams. He created it himself on the laser cutter using about US$2 in materials.

Then, he placed a piece of cowhide inside the Glowforge and sent a design for a cover for a Moleskine notebook from an iPad to the machine. Pulses of light began to glow inside the laser cutter as it burned stitch holes into the leather, followed by a rectangular cut that formed the outer edges of what would become the notebook cover. The machine, which Shapiro says is about a year away from shipping, is about the size of a wide suitcase.

IDEAL FOR 2D

Laser cutters are best suited to create 2D objects, though they can also be used to produce more intricate 3D objects like lamps or sculpture by cutting flat pieces that are assembled later.

Another startup, the Other Machine Co in San Francisco, has created a device, the Othermill, that acts like a reverse 3D printer.

Rather than building up a 3D object by creating layers of material, as a 3D printer does, the Othermill uses spinning bits to cut away at blocks of, for example, wood, metal or plastic. The machine, which costs US$2,199, weighs about 16 pounds, so it can be carted around in a car.

Danielle Applestone, chief executive of Other Machine, said the company had sold the machine to chocolatiers who milled wax molds for their candies on the device.

“There is no technological reason why everyday people don’t have access to manufacturing tools,” she said.

Gregg Wygonik, a designer who works for Microsoft, bought an Othermill to tinker around on personal projects in his garage. He has cut circuit boards with it and milled a sculpture out of wax. Wygonik said computer-controlled milling machines were normally aimed at hard-core engineer types, but not the Othermill.

“They’ve taken that edge off and made it very accessible,” he said. “It’s more about using these tools for artistic purposes and being inventive.”

It’s difficult to imagine desktop manufacturing tools becoming true mass-market products, especially when they are still relatively expensive. How many people will really want to buy them to make their own tote bags and iPhone cases when it’s so convenient to shop for them?

Shapiro says he believes there are plenty of people hungry to make more of the things in their lives but who simply lack the tools.

“It’s like we’re all eating fast food,” he said, “and we’ve forgotten how to cook.”

Most heroes are remembered for the battles they fought. Taiwan’s Black Bat Squadron is remembered for flying into Chinese airspace 838 times between 1953 and 1967, and for the 148 men whose sacrifice bought the intelligence that kept Taiwan secure. Two-thirds of the squadron died carrying out missions most people wouldn’t learn about for another 40 years. The squadron lost 15 aircraft and 148 crew members over those 14 years, making it the deadliest unit in Taiwan’s military history by casualty rate. They flew at night, often at low altitudes, straight into some of the most heavily defended airspace in Asia.

Beijing’s ironic, abusive tantrums aimed at Japan since Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi publicly stated that a Taiwan contingency would be an existential crisis for Japan, have revealed for all the world to see that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) lusts after Okinawa. We all owe Takaichi a debt of thanks for getting the PRC to make that public. The PRC and its netizens, taking their cue from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), are presenting Okinawa by mirroring the claims about Taiwan. Official PRC propaganda organs began to wax lyrical about Okinawa’s “unsettled status” beginning last month. A Global

Taiwan’s democracy is at risk. Be very alarmed. This is not a drill. The current constitutional crisis progressed slowly, then suddenly. Political tensions, partisan hostility and emotions are all running high right when cool heads and calm negotiation are most needed. Oxford defines brinkmanship as: “The art or practice of pursuing a dangerous policy to the limits of safety before stopping, especially in politics.” It says the term comes from a quote from a 1956 Cold War interview with then-American Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, when he said: ‘The ability to get to the verge without getting into the war is

Like much in the world today, theater has experienced major disruptions over the six years since COVID-19. The pandemic, the war in Ukraine and social media have created a new normal of geopolitical and information uncertainty, and the performing arts are not immune to these effects. “Ten years ago people wanted to come to the theater to engage with important issues, but now the Internet allows them to engage with those issues powerfully and immediately,” said Faith Tan, programming director of the Esplanade in Singapore, speaking last week in Japan. “One reaction to unpredictability has been a renewed emphasis on