Taiwan’s art scene is in many ways the artistic vanguard of Chinese history and culture — established galleries like Tina Keng (耿畫廊) and Lin & Lin (大未來林舍畫廊) frequently exhibit works by prominent Taiwanese and Chinese artists. However, some of the younger galleries like Galleria H (恆畫廊) — a chic and intimate space devoted to contemporary art on Xinsheng South Road – has been seeking to expand its scope to include artists from outside the Chinese-speaking world, as well as showcasing artwork that addresses messier themes like cross-cultural identity, multiculturalism and belonging.

Their current exhibition, I Don’t Belong (我不屬於), reflects Japanese-Taiwanese curator Nobuo Takamori’s personal struggle with figuring out his own place as a mixed-race polyglot in Taiwanese society.

PERSONAL ANGLE

Photo: Dana Ter, Taipei Times

“Japanese was my first language, then I learned Taiwanese (Hoklo), Mandarin and English, but now, Japanese is my weakest language,” Takamori says to me in English, flustered and confused, as if he were still trying to make sense of it.

The exhibition features the works of six female artists from around Asia, all handpicked by Takamori. Each of their works explores the overarching concept of finding one’s place as an expatriate and/or a multicultural, multilingual person in a modern urban setting.

“It was a tricky selection process since I am a male curator choosing works by female artists,” Takamori says.

Photo courtesy of Galleria H

Takamori did not initially intend for the exhibition to be composed entirely of works by women. Rather, he set out looking for artwork that had a personal storytelling element. It so happened that all the artists he chose were female.

“A lot of art galleries are focused more on the grand scale and bigger conceptual issues like globalization,” Takamori says. “But I feel that the best way to touch the viewer is through personal storytelling.”

He adds that “there are many artists who are talented in telling the female narrative — they don’t necessarily need to be ... female.”

Photo: Dana Ter, Taipei Times

The inspiration for I Don’t Belong started three years ago, when Takamori says he was “compelled to find out more about people similar to me.”

He joined a research project at Taipei’s Academia Sinica (中央研究院) on the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) expulsion of Japanese citizens living in Taiwan in the late 1940s. Although many of these people were born and raised in Taiwan, they were repatriated to a “homeland” which they knew very little of.

This resonated with Takamori who had artist friends with Japanese citizenship but grew up in Taiwan and were having problems finding visa sponsorship to allow them to continue living and creating art here.

Photo: Dana Ter, Taipei Times

An increasing number of “global citizens” face similar issues today. Growing up in multiple countries or in countries that are ethnically heterogeneous, these people exist between worlds and may not have allegiance to any one nation. The country — or countries — which they consider to be “home” may not be the same as what their passport states.

When translated into art, the results are simultaneously beautiful and bizarre. Images and ideas are not what they seem and it’s the subtleties that encapsulate what it really means to be a citizen of the world — seemingly fitting in but nevertheless always standing out.

IN BETWEEN FANTASY AND REALITY

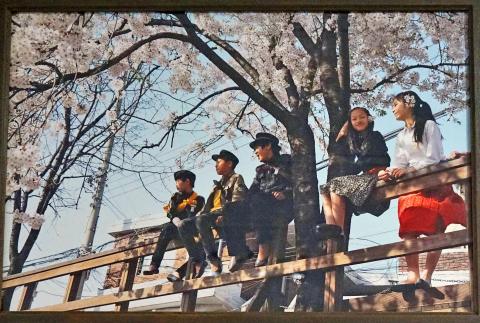

Closest to Takamori’s experience is that of Korean-Japanese artist Kim In-sook. Her photographs of students at Korean international schools in Japan reflects the identity crisis she faced growing up in Osaka with her paternal roots being from North Korea.

The images in Between Two Koreas and Japan seem to depict happy children playing outdoors but upon closer inspection, something in the composition is off. First, some of the students seem racially ambiguous. Kim was especially intrigued by schools that followed the North Korean education system. Her shots of elementary school boys dressed in Korean military-style attire with sashes and lapel pins, set against distinctly Japanese sceneries with cherry blossom trees in the background, are especially evocative.

The portraits draw out, in the most simplistic terms, the historical tension between North Korea, South Korea and Japan — and how it has marked the lives of people like Kim.

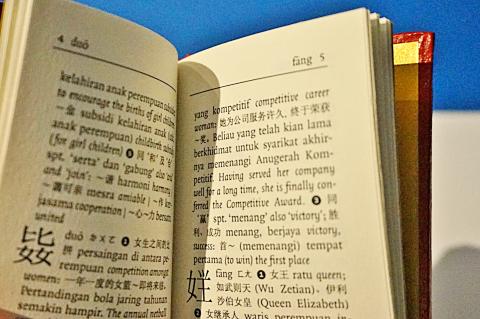

TypoKaki (kaki means “feet” in Bahasa), a Malaysian typography and design company, also tackles the question of multicultural existence, but through the (mis)use of language. The design team trio created multiple copies of books resembling Mao Zedong’s (毛澤東) Little Red Book. But far from containing political discourse, Women’s Word (女人的字) is a humorous dictionary consisting of made-up words which relate to experiences unique to women.

All of the words contain the Chinese character for women, nu (女), in them and they come with definitions in Chinese, English and Bahasa — the three main languages spoken in Malaysia. Since one of the made-up words is “wa” — “envy that stems from a polygamous relationship” — it’s obvious that TypoKaki is in sync with the world of dating and relationships today.

Au Sow-yee (區秀詒), who also hails from Malaysia, uses videography to create a fictional island, Mengkerang, located in Southeast Asia where people of different races coexist peacefully. Au interviewed her friends, asking them to describe their idea of utopia which she then compiled into a video named A Day Without Sun in Mengkerang.

Alongside the video projection, on the gallery’s wall, are historical documents printed on slabs of wood. They incorporate actual texts like the Federation of Malaya Independence Act of 1957 from which Malaya (present-day Malaysia) gained independence from British colonial rule. But Au interweaves her own clauses into the text, spelling out her vision for the fictional island. “Mengkerang is the last attachment of pseudo-ethnics for people with no sense of identity.”

Given how art tends to be associated with a specific country or culture, Takamori has done a particularly skilled job at curating an exhibition that breaks down traditional categories like “Chinese” or “Taiwanese” art.

Although identity and belonging are serious topics, there’s a good dose of humor in the artwork which helps to draw in the viewer. More importantly, the intermeshing of fantasy with reality is a fitting representation of the world that many “global citizens” live in — and it’s nice to finally have some aesthetic acknowledgment of such an existence.

This is the year that the demographic crisis will begin to impact people’s lives. This will create pressures on treatment and hiring of foreigners. Regardless of whatever technological breakthroughs happen, the real value will come from digesting and productively applying existing technologies in new and creative ways. INTRODUCING BASIC SERVICES BREAKDOWNS At some point soon, we will begin to witness a breakdown in basic services. Initially, it will be limited and sporadic, but the frequency and newsworthiness of the incidents will only continue to accelerate dramatically in the coming years. Here in central Taiwan, many basic services are severely understaffed, and

Jan. 5 to Jan. 11 Of the more than 3,000km of sugar railway that once criss-crossed central and southern Taiwan, just 16.1km remain in operation today. By the time Dafydd Fell began photographing the network in earnest in 1994, it was already well past its heyday. The system had been significantly cut back, leaving behind abandoned stations, rusting rolling stock and crumbling facilities. This reduction continued during the five years of his documentation, adding urgency to his task. As passenger services had already ceased by then, Fell had to wait for the sugarcane harvest season each year, which typically ran from

It is a soulful folk song, filled with feeling and history: A love-stricken young man tells God about his hopes and dreams of happiness. Generations of Uighurs, the Turkic ethnic minority in China’s Xinjiang region, have played it at parties and weddings. But today, if they download it, play it or share it online, they risk ending up in prison. Besh pede, a popular Uighur folk ballad, is among dozens of Uighur-language songs that have been deemed “problematic” by Xinjiang authorities, according to a recording of a meeting held by police and other local officials in the historic city of Kashgar in

It’s a good thing that 2025 is over. Yes, I fully expect we will look back on the year with nostalgia, once we have experienced this year and 2027. Traditionally at New Years much discourse is devoted to discussing what happened the previous year. Let’s have a look at what didn’t happen. Many bad things did not happen. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) did not attack Taiwan. We didn’t have a massive, destructive earthquake or drought. We didn’t have a major human pandemic. No widespread unemployment or other destructive social events. Nothing serious was done about Taiwan’s swelling birth rate catastrophe.