Mother knows best when it comes to running the world’s second-largest real estate company.

That’s one conclusion from the graft trial of Hong Kong’s billionaire Kwok brothers, which ended today with Thomas Kwok (郭炳江) jailed for five years for corrupting Rafael Hui (許仕仁), the city’s chief secretary from 2005 to 2007. His younger brother Raymond Kwok (郭炳聯), who was also a defendant in the case, was acquitted of all charges.

Thomas and Raymond wrested control of developer Sun Hung Kai Properties Ltd from their eldest brother Walter (郭炳湘) in 2008 after their mother intervened, according to testimony heard in the trial which started seven months ago.

Photo: Reuters

Even though the matriarch, Kwong Siu-hing (鄺肖卿), didn’t hold a position in the firm at the time of Walter’s ouster, she called the shots by controlling the trust that holds the family’s stake in the US$42.7 billion company. Kwong, now 86, stepped in to lead the company’s board in 2008 and stripped Walter from the family trust in 2010 before ceding chairmanship to her two younger sons in 2011.

The family had kept private that Walter had been acting erratically since he was kidnapped by a gangster in 1997, testimony revealed. His troubles were only disclosed to shareholders more than a decade later when he stepped back from running the company.

“Any family affair can influence corporate performance greatly,” said Joseph Fan, a professor who researches governance issues in family firms at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. “Many Chinese families do not have family governance mechanisms in place, including the Kwok family.”

Photo: AFP

CORPORATE GOVERNANCE

The case speaks to broader corporate governance issues in Hong Kong, where family businesses dominate the economy. The six wealthiest men and their families build the majority of properties, dominate telecommunications and control bus routes and port access.

The court heard how Hui was hired as a HK$15 million-a-year adviser to Sun Hung Kai under a secret agreement, and how payments were hidden and salaries routed via personal bank accounts and intermediaries. At times, it appeared as if the conglomerate was run more like a mom-and-pop operation than the listed property giant it is.

“It just underlines it’s a family company even though it’s a big one,” said David Webb, a Hong Kong-based investor and shareholder activist. “There’s always some investment risk associated with the profile of owners of companies, whether they’re government controlled or family controlled.”

BEST-MANAGED

Sun Hung Kai has won a slew of corporate governance awards. It was named Asia’s best-managed company for four straight years in an annual poll conducted by Euromoney magazine and it took the top award last year from Corporate Governance Asia, a Hong Kong-based publication.

“The board sets the company’s strategies and ensures good governance, and the executive committee makes all major commercial decisions collectively,” Sun Hung Kai said in a response to questions, while declining to comment on the trial. It’s committed to the highest levels of governance, it said.

Fiona Wan, a spokeswoman for the Kwok’s family trust, declined to comment about Kwong’s control of the family fortunes.

Sun Hung Kai said on Dec. 19 the convictions of Thomas Kwok and executive director Thomas Chan (陳鉅源) haven’t affected its business and operations. Adam Kwok, Thomas’s 31-year-old son, who had been appointed as an alternate director for his father when the latter was charged in 2012, was appointed as an executive director. Shares rose the most in two-and-a-half months yesterday when they resumed trading for the first time since the verdicts.

FOUNDING FATHER

In cases where family members own a bulk of the company, outside shareholders are sometimes left out of the decisions. Corporate governance norms are especially hard to attain at sensitive times such as the death of the patriarch or matriarch, and decisions are made behind closed doors, as heard in the trial of the Sun Hung Kai chairmen.

The Kwok family trust has the largest stake in Sun Hung Kai, co-founded in 1963 by the brothers’ father, Kwok Tak-seng (郭得勝). Walter took over as chairman after his father’s death until he was forced out in 2008 on the grounds of mental illness.

Walter said at the time he didn’t have any such disorder and sued his siblings for libel, a case that was later dropped. He alleged that his brothers accused him of making unwise investment decisions and called him a liar, according to a court filing.

The defense of Thomas, 63, and Raymond, 61, against charges of corrupting Hui relied on their brother Walter’s emotional and physical health.

SECRET AGREEMENT

Thomas Kwok said he struck an unwritten consultancy agreement with Hui in 2003 for HK$15 million (US$1.9 million), which was the highest ever paid to an adviser by the company. He testified the deal was concealed because Thomas promised his mother he wouldn’t do anything to provoke Walter, who was opposed to hiring Hui at the time.

Walter was depressed after an operation to remove a tumor and a falling-out with his wife, according to Thomas’s testimony.

Thomas paid the bulk of the money out of his own pocket and considered asking his mother for the sum back, according to his testimony.

“I hoped that when things got better I could ask my mother,” he told the court.

Another instance where Kwong stepped in was an argument Thomas and Walter had over lease negotiations in 2003 for the International Finance Center, a landmark office tower and shopping mall built by Sun Hung Kai, Henderson Land Development Co and MTR Corp, the government-owned railway operator.

KIDNAPPING, RANSOM

Walter didn’t trust the colleagues put in charge of negotiating tenancy agreements with financial clients and retailers, Thomas testified.

“The matter was referred to our mother for discussion,” he told the court. “Eventually our mother accommodated him and asked me to hand it back, although I was upset about it.”

Walter’s illness started after his kidnapping in 1997 and release on a US$77 million ransom. He was removed from the board almost 11 years later, after he accused senior executives including Chan of wrongdoing, according to testimony.

His brothers at first wanted Walter to stay despite an independent director saying he should leave, Clare Montgomery, Thomas’s lawyer said.

“Walter Kwok was not well and did not take the opportunity to recover, to the point that even his mother thought he had to go,” she told the court. The truth is Walter “was a very sad part of the picture.”

GOD’S SAY

Walter was not a party to the trial, and while the prosecution said the defense “vilified” him, he said in two statements after the verdicts that he believed Thomas was innocent and he was very glad that Raymond was acquitted.

“The issue raised lots of arguments and rumors. What is right and what is wrong, I think God will have his say on the matter,” Walter said.

He said he had confidence in Raymond’s leadership of the company, which he had no intention of returning to.

Their mother decided who got how much of the real estate empire. She had the power to exclude Walter from the family trust in 2010 and also to restore his share, as she did just earlier this year. All three brothers hold around 7 percent of the company under their own names while the 33 percent stake held by the family trust is separated into three offshore companies.

The matriarch has been reducing her interest in the company after transferring shares from the family trust to her sons. Her stake dropped from 43.4 percent in October 2013 to 26.4 percent as of Nov. 17. She is in “very poor health” and has suffered a stroke, Montgomery told the court on Dec. 22 when making a mitigation plea for Thomas Kwok.

STOCK LOSS

Thomas Kwok was also banned from being a company director for five years by Judge Andrew Macrae who delivered the sentences today. Kwok’s jail term was lower than the maximum of seven years after Macrae considered factors including his good character, “genuinely motivated by his Christian faith.”

Sun Hung Kai shares have risen 5.1 percent since the March 2012 arrests of Thomas and Raymond, although the stock lost US$4.9 billion on the day of their arrest. It is among the top 10 best-performing stocks in Hong Kong this year, along with three other property companies.

Simon Property Group Inc, the biggest US mall owner, is the world’s biggest real estate company by market capitalization, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

The late Kwok started the company with two others including Lee Shau-kee (李兆基) of Henderson Land, who is still a director. Sun Hung Kai now owns the city’s two tallest skyscrapers among others in Hong Kong and China, as well as non-property businesses including SmarTone Telecommunications Holdings Ltd and Kowloon Motor Bus Co.

Henderson Land controls, aside from its property business, the main gas provider in Hong Kong. New World Development Co, owned by the family of billionaire Cheng Yu-tung (鄭裕彤), owns two of the main bus companies. Li Ka-shing (李嘉誠), who owns developer Cheung Kong Holdings Ltd, controls port operator Hongkong International Terminals Ltd and one of the two electricity suppliers in Hong Kong.

BIG PICTURE

“The large Asian family companies have very strong economic positions in their home territories,” said Webb. “Their oligopolies can pretty much run themselves with professional management. It’s the big picture capital allocation decisions where the family would have an impact.”

Family relationships are often seen as dangerous for the management of listed companies, according to David Donald, a law professor at Chinese University of Hong Kong, who has written on corporate and bribery law.

“However, if a company has lasted for more than one generation, it is likely that the bonds of family loyalty are in sync with duties of management under the law,” he said. “If family loyalty were to go against the law, then the company wouldn’t survive very long.”

The case is Hong Kong Special Administrative Region v Rafael Hui, Thomas Kwok, Raymond Kwok, Thomas Chan and Francis Kwan, HCCC98/2013, in Hong Kong’s High Court.

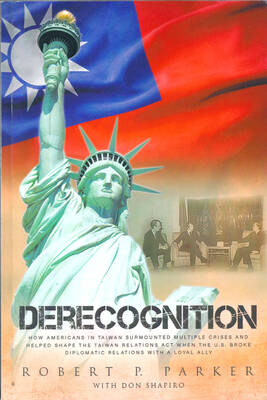

One of the biggest sore spots in Taiwan’s historical friendship with the US came in 1979 when US president Jimmy Carter broke off formal diplomatic relations with Taiwan’s Republic of China (ROC) government so that the US could establish relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Taiwan’s derecognition came purely at China’s insistence, and the US took the deal. Retired American diplomat John Tkacik, who for almost decade surrounding that schism, from 1974 to 1982, worked in embassies in Taipei and Beijing and at the Taiwan Desk in Washington DC, recently argued in the Taipei Times that “President Carter’s derecognition

This year will go down in the history books. Taiwan faces enormous turmoil and uncertainty in the coming months. Which political parties are in a good position to handle big changes? All of the main parties are beset with challenges. Taking stock, this column examined the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) (“Huang Kuo-chang’s choking the life out of the TPP,” May 28, page 12), the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) (“Challenges amid choppy waters for the DPP,” June 14, page 12) and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) (“KMT struggles to seize opportunities as ‘interesting times’ loom,” June 20, page 11). Times like these can

JUNE 30 to JULY 6 After being routed by the Japanese in the bloody battle of Baguashan (八卦山), Hsu Hsiang (徐驤) and a handful of surviving Hakka fighters sped toward Tainan. There, he would meet with Liu Yung-fu (劉永福), leader of the Black Flag Army who had assumed control of the resisting Republic of Formosa after its president and vice-president fled to China. Hsu, who had been fighting non-stop for over two months from Taoyuan to Changhua, was reportedly injured and exhausted. As the story goes, Liu advised that Hsu take shelter in China to recover and regroup, but Hsu steadfastly

You can tell a lot about a generation from the contents of their cool box: nowadays the barbecue ice bucket is likely to be filled with hard seltzers, non-alcoholic beers and fluorescent BuzzBallz — a particular favorite among Gen Z. Two decades ago, it was WKD, Bacardi Breezers and the odd Smirnoff Ice bobbing in a puddle of melted ice. And while nostalgia may have brought back some alcopops, the new wave of ready-to-drink (RTD) options look and taste noticeably different. It is not just the drinks that have changed, but drinking habits too, driven in part by more health-conscious consumers and