Exiting the Huilong (迴龍) MRT Station and following a sign that reads Losheng (Happy Life) Sanatorium (樂生療養院), you immediately find yourself surrounded by a huge construction site where a Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) maintenance depot will soon be located. Walking uphill, you pass several old houses that are what is left of the original public leprosarium, eroded and fenced in as the ongoing construction has triggered landslides, causing buildings to crack.

Nearby there stands a few rows of prefabricated sheds, where the aging former patients with Hansen’s disease, also known as leprosy, have lived since they were forcefully evicted from the sanatorium compound, mostly demolished to make way for the maintenance depot, over 10 years ago. Walking further up, you encounter a columbarium and eventually reach your destination: a circus tent glittering under the dark sky, looking eerily beautiful.

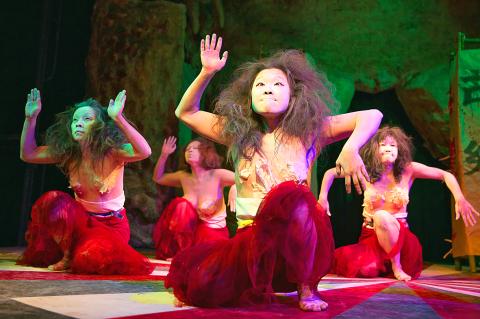

Inside, several women painted white and half-nude perform stunts on stage. Their bodies are contorted; their facial expressions are grotesque, almost unworldly. In a climactic act, Japanese butoh dancer and choreography Qin Kanoko thrusts with a long bamboo pole against the setting that mimics the limestone caves in Okinawa. She grimaces and shivers amid fire. Suddenly the curtain drops, revealing a skyline dominated by skyscrapers where the rich and powerful dwell.

Photo Courtesy of Chen You-wei

Ghost Circus (幽靈馬戲團) is the latest work by Kocyonanten Butoh Dance Group (黃蝶南天舞踏團) and is held to celebrate the troupe’s 10th anniversary. When Qin founded the butoh group in Taipei in 2005, she wanted to “bring down” the performance art form from its highbrow status.

“By bringing it down, I mean to return to real life, to earth,” Qin says. For Qin, a revelation occurred in 2000 when she worked with a group of people living in the slums surrounding a landfill in the Philippines. Professionally trained as a butoh artist in Japan, Qin suddenly realized her art had nothing to do with the “real” world. Her gaze has turned to the underprivileged and the deprived ever since.

She soon started working with some Taiwanese troupes, later settling in Taiwan. Over the past decade, her group has performed several productions at Losheng Sanatorium, where patients with leprosy were segregated from the rest of the society. Many have passed away; those who remain face the forced destruction of the place they have called home.

Photo Courtesy of Chen You-wei

The butoh performances are conceived as rituals to comfort the spirits and wandering ghosts who suffered from state violence when they were alive.

“The body of a butoh dancer is a medium through which the silent spirits voice,” the 50-year-old artist says.

Though fiercely political and deeply spiritual, the troupe’s performances often adopt populist vocabularies, inspired by local temple festivities, such as pole dance shows that are performed to entertain the dead. Qin says such butoh works are uniquely Taiwanese. “In Japan, it is hard to find a butoh performance like these ... Japanese butoh artists have to try very hard to find things, such as going to and living in a farming village. In Taiwan, on the other hand, the dead is always among the living, close to us, in a pole dance show,” she says.

One of the biggest sore spots in Taiwan’s historical friendship with the US came in 1979 when US president Jimmy Carter broke off formal diplomatic relations with Taiwan’s Republic of China (ROC) government so that the US could establish relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Taiwan’s derecognition came purely at China’s insistence, and the US took the deal. Retired American diplomat John Tkacik, who for almost decade surrounding that schism, from 1974 to 1982, worked in embassies in Taipei and Beijing and at the Taiwan Desk in Washington DC, recently argued in the Taipei Times that “President Carter’s derecognition

This year will go down in the history books. Taiwan faces enormous turmoil and uncertainty in the coming months. Which political parties are in a good position to handle big changes? All of the main parties are beset with challenges. Taking stock, this column examined the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) (“Huang Kuo-chang’s choking the life out of the TPP,” May 28, page 12), the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) (“Challenges amid choppy waters for the DPP,” June 14, page 12) and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) (“KMT struggles to seize opportunities as ‘interesting times’ loom,” June 20, page 11). Times like these can

June 23 to June 29 After capturing the walled city of Hsinchu on June 22, 1895, the Japanese hoped to quickly push south and seize control of Taiwan’s entire west coast — but their advance was stalled for more than a month. Not only did local Hakka fighters continue to cause them headaches, resistance forces even attempted to retake the city three times. “We had planned to occupy Anping (Tainan) and Takao (Kaohsiung) as soon as possible, but ever since we took Hsinchu, nearby bandits proclaiming to be ‘righteous people’ (義民) have been destroying train tracks and electrical cables, and gathering in villages

Dr. Y. Tony Yang, Associate Dean of Health Policy and Population Science at George Washington University, argued last week in a piece for the Taipei Times about former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) leading a student delegation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that, “The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world” (“Ma’s Visit, DPP’s Blind Spot,” June 18, page 8). Yang contends that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has a blind spot: “By treating any