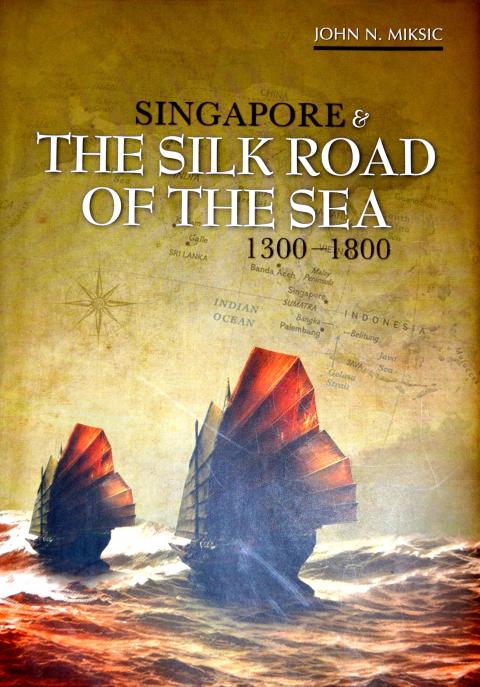

Mention the name Singapore or the Silk Road and chances are vivid, picturesque images will immediately come to mind. Singapore suggests a rich modern maritime city, one that grew from a simple island through the efforts of a far-sighted Sir Stamford Raffles who obtained it for the British East India Company in 1819. The Silk Road, on the other hand, is seen to date much farther back. It conjures up images of age-old caravans snaking along a trade route that had linked East and West from the days of Han Dynasty China (206 BC to 220AD) and the Roman Empire. Yet a common misconception lies hidden here, namely that though the Silk Road had existed for millenia when Raffles “founded” Singapore, he took a barely inhabited island and made it into a stellar city. This is the misconception that John N. Miksic aims to dispel with Singapore and the Silk Road of the Sea 1300—1800.

Miksic, who teaches archaeology and history at the University of Singapore, does not dispute the claims of the “land silk route.” Instead, he sets about to show that land routes linking China, Southeast Asia, India and the Mediterranean were by no means the only ones. The Silk Road of the Sea dates back just as far, if not farther, and Singapore would prove to be a major player in that history. Situated at the eastern end of the Strait of Malacca, its location made it a vital trade port, instrumental in linking three seas: the South China Sea, the Java Sea and the Indian Ocean. And given the cargo capabilities of ships, the trade along this “Silk Road” could have more volume and be more frequent than land caravans.

Certainly when the early 16th century Portuguese first entered Asian waters, the question arose how they would find their way to the fabled but mysterious Spice Islands since these were totally uncharted waters for the West? Miksic’s first four chapters provide the answer. The trade routes were well in place as early as the 3rd or 4th century BC and very active. This trade never ceased. Miksic’s main focus, however, will be on the period of 1300 to 1800, Singapore’s heyday and the time before the arrival of Raffles. In that period the fortunes of Singapore rose and fell and Miksic, as an archaeologist can provide demonstrable proof.

Using the results of extensive excavations in Singapore, the book’s middle chapters leave little doubt as to the imports and exports that passed through this port city century to century. With about 25 years of archaeological research, innumerable artifacts have been discovered, some areas like St. Andrew’s Cathedral yielding a ratio of 519 items per cubic meter. Raffles was aware of this history from the Malay Annals and that proved instrumental in his selection. Other potential locations were available, but Singapore had history on its side, and, for the history-minded Raffles, that made it the perfect way station between India and China, the place to tap into an already existing network.

Singapore and its exemplary excavations are prominent in the book. But other informative points of interest are present as well. Passage through the Strait of Malacca stands in contrast to the more treacherous southern coast of Sumatra. Seasonal monsoons governed east-west movements. Multiple nations participated in trade but the earliest ships of the period were not Chinese but those of Malayo-Polynesians (read Austronesian). China entered once the Han Dynasty was established and had a vacillating on-again, off-again participation. The Yuan Dynasty did not have any compunction against trade, allowing Marco Polo to follow sea routes on his return to Europe. The succeeding Ming Dynasty restricted trade until the Yongle (永樂) Emperor reopened it, bringing Zheng He (鄭和) and his fleets temporarily into the picture, but then China withdrew. Western control of the strait would first go to the Portuguese and then the Dutch who weakened Singapore’s role by requiring trade to stop at Batavia. Raffles and the British would bring it back to life.

The final chapters of the book expand the details of this vast trade network by placing Singapore in the context of its trading neighbors. Miksic’s one regret is that while trade extended from Japan’s southern Ryukyu Islands to Madagascar, none of the locations along those routes have comparable excavations allowing him to measure how large Singapore was in comparison. This seminal book encourages such, and also opens the door for future historical books and even novelists to expound on the vast history of the Silk Road of the Sea, a point that Taiwanese readers with their own Austronesian past can relate to.

Before the recall election drowned out other news, CNN last month became the latest in a long line of media organs to report on abuses of migrant workers in Taiwan’s fishing fleet. After a brief flare of interest, the news media moved on. The migrant worker issues, however, did not. CNN’s stinging title, “Taiwan is held up as a bastion of liberal values. But migrant workers report abuse, injury and death in its fishing industry,” was widely quoted, including by the Fisheries Agency in its response. It obviously hurt. The Fisheries Agency was not slow to convey a classic government

Not long into Mistress Dispeller, a quietly jaw-dropping new documentary from director Elizabeth Lo, the film’s eponymous character lays out her thesis for ridding marriages of troublesome extra lovers. “When someone becomes a mistress,” she says, “it’s because they feel they don’t deserve complete love. She’s the one who needs our help the most.” Wang Zhenxi, a mistress dispeller based in north-central China’s Henan province, is one of a growing number of self-styled professionals who earn a living by intervening in people’s marriages — to “dispel” them of intruders. “I was looking for a love story set in China,” says Lo,

It was on his honeymoon in Kuala Lumpur, looking out of his hotel window at the silvery points of the world’s tallest twin skyscrapers, that Frank decided it was time to become taller. He had recently confessed to his new wife how much his height had bothered him since he was a teenager. As a man dedicated to self-improvement, Frank wanted to take action. He picked up the phone, called a clinic in Turkey that specializes in leg lengthening surgery — and made a booking. “I had a lot of second thoughts — at the end of the day, someone’s going

The next few months will be critical in determining the future of the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP). Following party founder Ko Wen-je’s (柯文哲) arrest in September last year, Huang Kuo-chang (黃國昌) effectively became the de facto face of the party and officially became chairman in January. While Ko frequently criticized the ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and insinuated sinister intentions on the part of the DPP’s New Tide faction, his era was largely defined by the TPP slogan “rational, pragmatic, scientific,” albeit defined largely by his definition of what that meant. The tone and language used by the TPP changed dramatically