I met Andrew Harvey in the 1970s when he was a fellow of Oxford’s All Souls College. At 21 years old, he was the youngest fellow the college had ever elected. He taught literature to a handful of select graduate students, and I remember how, having arrived for lunch, I sat in on the tail end of a tutorial on Chekhov in which he was insisting that literature would never change the world.

I already suspected that English literature was a pyramid without a top, that it lacked a mystical, spiritual dimension except in a small handful of poets such as Herbert, Traherne and Hopkins. I have no idea to this day whether Harvey shared that view, though it would seem likely. But shortly after we met he left Oxford to pursue spiritual enlightenment in India. Today, Harvey lives in the US and is the author of some 30 books, the great majority on the mystical traditions of all the religions, both inside and outside what is conventionally termed “literature.”

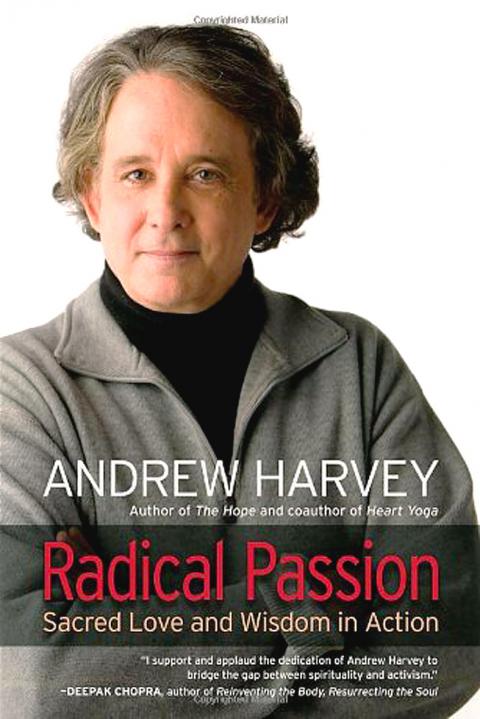

His new book, Radical Passion, in a bulky collection of his introductions to other people’s books, together with interviews he’s given over the years.

But it isn’t hard to discern his current concerns, outlined in a more systematic manner in his previous book The Hope: A Guide to Sacred Activism (2009).

What he believes is that the world is confronting a unique environmental crisis, with species disappearing at an unprecedented rate, potentially catastrophic climate change, hideous exploitation of animals and corporate capitalism that is never going to reform itself.

The answer lies, Harvey believes, not with any one religion, but with the rediscovery of the feminine principle that’s present within all forms of spirituality.

Harvey’s road to this position lay through his becoming, at 27, a disciple of a 17-year-old Indian guru known as Mother Meera (who he saw manifest herself in a blaze of celestial light in 1979, after which he never again believed in Western materialism). He moved with her to Germany, but eventually broke with her after she declared he was no longer gay, and had to leave his long-time lover, marry a woman and father children.

As is often the case in middle age, Harvey’s various concerns now appear to coalesce.

Literature, for example, features prominently in this new book, with pieces on the poets Rilke, Hesse and Rumi, alongside frequent references to spiritual teachers such as Jesus, the Dalai Lama (though he criticizes him at one point), Ramakrishna, Aurobindo (“the greatest mystical philosopher of Hinduism, and perhaps of all human history”) and Bede Griffiths, the UK-born Benedictine monk who had pioneered a dialogue between Hinduism and Christianity.

What’s especially interesting is that Harvey’s activism centers on issues that you can panic over even if you are not of a religious disposition. It’s only in his solution that he’s religious. But even here he has little time, for instance, for “transcendence,” let alone the illusory nature of reality taught by some Hindu sects. The planet that’s in such need of help is far from illusory, he says, and couldn’t be more real.

The very concept of social protest, too, is opposed to some people’s idea of spirituality. What makes Harvey special, apart from his exceptional literary erudition, is his commitment to social activism based on spiritual tenets. The foundation that he started and runs is called The Institute for Sacred Activism.

As for mother goddesses, some that Harvey cites are the Virgin Mary, (though he believes she wasn’t an actual virgin), together with Europe’s Black Madonnas, the ancient Egyptian Isis, the many Hindu manifestations of the divine feminine, violent and cruel though some of them seem, the Roman mother-goddess Cybele, the pre-Christian matriarchal religions of Europe, and New World shamanistic traditions. The restoration of these may be reminiscent of 1960s longings, but Harvey isn’t one to be held back by such trivialities.

It mustn’t be thought that Harvey is only interested in Oriental religions. The recovery of “the full range, power and glory of the Christian mystical tradition” is vital too, he writes.

And the truth is that Harvey teaches many things.

At one point, in an illuminating interview with poet and novelist Rose Solari, he says that what the great teachers — Jesus, Buddha — have tried to tell us is that each of us is divine, but that we’ve responded by making religions out of the teachers themselves. As a result, Harvey isn’t a Christian or a Buddhist or a Sufi or even a Hindu, but an enthusiast for the great mystics from all these traditions. They have, as Aldous Huxley observed long ago in his The Perennial Philosophy, far more in common than the superficial differences that keep them apart.

Later in the interview Harvey outlines the horrors of the modern world — its pollution, its trivializing media, its self-serving politicians, the condition of the world’s poor, and the devastation of nature. He concludes that what is needed is for everyone who cares about the future of the earth to come out onto the streets and “say no to pollution, no to the proliferation of nuclear arms, no to the destruction of the earth.”

But because patriarchy, rationalism, fear and guilt have in large part created this situation, the birth of a spiritual consciousness of the Sacred Feminine is what will lead people into this form of action.

Harvey is no solemn preacher, but a lively, witty and often funny commentator. There’s an excellent hour-long interview with him on YouTube titled “The Death and the Birth,” uploaded by conscioustv, that will more than prove this point.

“One world is clearly dying in agony around us,” Harvey writes. “Another is trying to rise, phoenix-like, from its ashes.”

Whether environmentalists marching under the banner of a mother goddess will ever come about might be debatable. But it’s hard not to hope that something like the regeneration Harvey stands for will have an increasing public presence as our doom-laden century progresses.

The canonical shot of an East Asian city is a night skyline studded with towering apartment and office buildings, bright with neon and plastic signage, a landscape of energy and modernity. Another classic image is the same city seen from above, in which identical apartment towers march across the city, spilling out over nearby geography, like stylized soldiers colonizing new territory in a board game. Densely populated dynamic conurbations of money, technological innovation and convenience, it is hard to see the cities of East Asia as what they truly are: necropolises. Why is this? The East Asian development model, with

June 16 to June 22 The following flyer appeared on the streets of Hsinchu on June 12, 1895: “Taipei has already fallen to the Japanese barbarians, who have brought great misery to our land and people. We heard that the Japanese occupiers will tax our gardens, our houses, our bodies, and even our chickens, dogs, cows and pigs. They wear their hair wild, carve their teeth, tattoo their foreheads, wear strange clothes and speak a strange language. How can we be ruled by such people?” Posted by civilian militia leader Wu Tang-hsing (吳湯興), it was a call to arms to retake

Desperate dads meet in car parks to exchange packets; exhausted parents slip it into their kids’ drinks; families wait months for prescriptions buy it “off label.” But is it worth the risk? “The first time I gave him a gummy, I thought, ‘Oh my God, have I killed him?’ He just passed out in front of the TV. That never happens.” Jen remembers giving her son, David, six, melatonin to help him sleep. She got them from a friend, a pediatrician who gave them to her own child. “It was sort of hilarious. She had half a tub of gummies,

The wide-screen spectacle of Formula One gets a gleaming, rip-roaring workout in Joseph Kosinski’s F1, a fine-tuned machine of a movie that, in its most riveting racing scenes, approaches a kind of high-speed splendor. Kosinski, who last endeavored to put moviegoers in the seat of a fighter jet in Top Gun: Maverick, has moved to the open cockpits of Formula One with much the same affection, if not outright need, for speed. A lot of the same team is back. Jerry Bruckheimer produces. Ehren Kruger, a co-writer on Maverick, takes sole credit here. Hans Zimmer, a co-composer previously, supplies the thumping