Appropriation has been contemporary art’s buzz word since Andy Warhol hung his Campell’s Soup Cans at an LA gallery in the early 1960s. Whether copying consumer products as Warhol did, or Roy Lichtenstein with comics, the replication of common (pop) objects — usually purged of their original context — for the purpose of creating art has been at the center of the Western picture-making tradition for at least 50 years. It’s also been its bete noire.

Jose Maria Cano works within this tradition, copying stuff of seemingly no lasting significance and turning it into largish encaustic (wax) paintings. A selection of the Spanish-born, London-based artist’s work is currently on view at Lin & Lin Gallery (大未來林舍畫廊), spanning the past six years in a show titled Dark Side of the Moon. It ends Nov. 10.

Cano is probably better known as a pop star. Forming a third of Mecano, a hugely successful Spanish pop group active in the 1980s and early 1990s, he has composed music for the likes of Julio Iglesias and the tenor Placido Domingo. He developed a deeper interest in drawing and encaustic, which he had learned when he was younger in the expectation that he would pursue a career in architecture. But in the 1990s, he traded in his rock stardom to pursue a career in fine art.

Photo courtesy of Lin & Lin Gallery

Cano’s earliest solo show revealed that he wasn’t afraid of making the personal public, appropriating autobiographical ephemera — documents, drawings, letters — for the purposes of laying bare the darker corners of the human psyche. This is Just Business put the crises and cruces of his messy divorce on display, depicting aggressive letters from his wife’s lawyers, tempered by drawings made by his son, who has Asperger’s syndrome. At root, marriage is a financial arrangement, the wax paintings suggested, and divorce is war, with children the main casualties.

He followed this up later with the subversive Masturbation (“Masturbation is the purest form of manipulation. People do it all the time, but no-one wants to talk about it”). Here is a man, you think, who isn’t afraid of letting it all hang out. With Dark Side of the Moon, however, he takes the viewer in a completely different direction, shifting from the personal to the public, while retaining the wax medium.

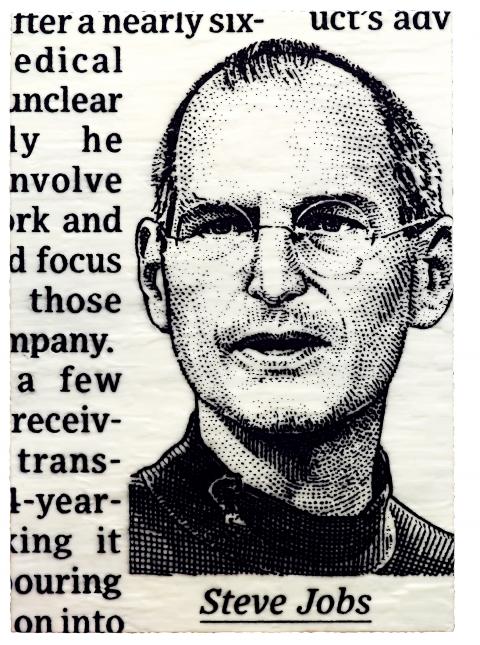

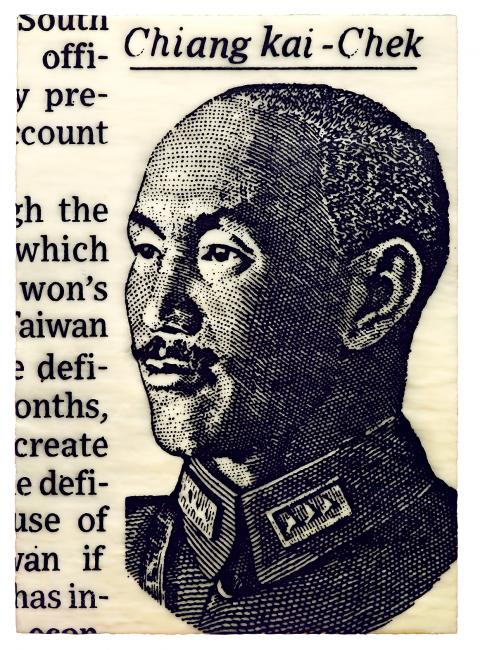

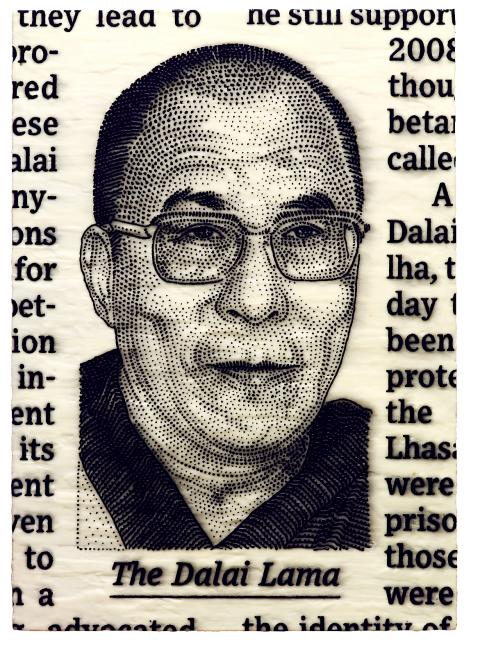

The gallery has assembled paintings from Cano’s Wall Street series, of which Wall Street 100 and Wall Street Wax Museum are on display. Captains of finance such as Bill Gates, Steve Jobs and Warren Buffett (all on display) feature prominently in the former, while the latter, situated in a different space, is given over to 10 works commissioned by a high-profile Asian collector, collectively titled China 10, and include Mao Zedong (毛澤東), Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石), Lee Teng-hui (李登輝) and the Dalai Lama.

Photo courtesy of Lin & Lin Gallery

Important people

Cano collectively dubs the figures in both series a “club of important people.” They are important because they’ve appeared as hedcuts — small portraits of newsmakers rendered in a stippled or pointillist manner — in the illustrious Wall Street Journal (WSJ), from which Cano appropriates and enlarges them into his 2.1m by 1.5m encaustic paintings.

The paintings hang in a shrine-like space, lights dimmed mausoleum-like to add an aura of the eternal. The paintings and their arrangement, the gallery and artist want us to know, serves as both a memorial and a testament to public figures who have a gained heroic status, if only at a particular place in time.

Photo courtesy of Lin & Lin Gallery

A third series, Raw Model, is displayed on the gallery’s second floor, and is taken from photographs of models that Cano found on the Internet.

Cano tells me the Wall Street 100 began as a jab at the hubris he witnessed all around him after moving to London in 1993. There he saw a moderate interest in the world of finance transform into a veritable obsession, where doctors and architects gave up their practices to become hedge fund managers. Prices in London skyrocketed, especially its art.

“Everyone else couldn’t pay the prices in London, or buy a home there,” Cano says. He added, noting the obvious irony of his work and the ideas that went into creating them, “most of my collectors loved [the paintings].”

Photo courtesy of Lin & Lin Gallery

All the paintings have been decontextualized from their original source. Like Jasper Johns’ targets and flags, we look at the portraits of these figures in a different way. The characters are silent and inscrutable, except for our previous knowledge of them. Shorn of their original context — the article they appeared in and the newspaper that published them — our own ideas about what these figures represent emerge.

Opportunist?

Being a good pop artist, Cano is unapologetically commercial (in the Warholian and Hirshian mode). And this is the point. Not only is Cano playing on the emotions stirred by these figures, but he’s also directing our attention to the commercial side of the exhibition enterprise, no different, perhaps, than Warhol’s Marilyn Diptych, exhibited soon after the actress’ death. The iconography of dictators, as many Chinese artists know (do we really need another Mao?) and the nouveau riche (who also purchase the works) become products that are sold at the high end of the art marketplace, while the artist himself alludes to our own implication as consumers (whether viewers or collectors) in the transaction.

Photo courtesy of Lin & Lin Gallery

Curiously, though, none of the works on display are for sale; a joke directed at other collectors, perhaps, or a gallery’s attempt to capitalize on the name of an increasingly popular contemporary artist by exhibiting his work.

At first, I was deeply suspicious of the collector’s choice of figures. It was either a crass attempt at publicity or a statement about some racial exclusion. After all, who would want Mao’s portrait hung over their bed. Financial industry bigwigs such as Bill Gates and Steve Jobs will obviously attract the attention of Taiwan’s captains of finance. But will Cano’s original criticisms come through?

Then again, conceptual art is not meant to be hung, but collected and stored. After thinking about the choices, however, a logic began to emerge. Juxtaposed with the capitalists in the other room, Cano is criticizing the largesse the WSJ is giving over to these figures, and the way media turns some into heroes without the underlying struggles that go into making them so.

In the 90 minutes I spoke with Cano, he kept pulling out his mobile phone to look for images of Egypt’s Fayum mummy encaustics — ancient portraits painted on board and placed on the deceased — to contextualize his own portraits in a broader historical framework. These enigmatic, though strongly realistic, entablatures symbolizing death allow us to wonder who these ancient figures were. When thought about in the context of this show, it forces us to think of how the reputation of Warren Buffett or Lee Kwan Yew (李光耀) will hold up to posterity.

Cano is certainly no Ai Weiwei (艾未未) in the degree in which he uses art to draw attention to political issues — something that conceptual and pop art have for the most part ignored over the past few decades. But he does represent a possible direction in which these kinds of artists will go in the future, remaining firmly entrenched in the commercial art system while using it to criticize the powers-that-be running it.

■ Dark Side of the Moon runs until Nov. 10 at Lin & Lin Gallery (大未來林舍畫廊), 16 Dongfeng St, Taipei City, (台北市東豐街16號), tel: (02) 2700-6866. Open Tuesdays to Sundays from 11am to 7pm.

One of the biggest sore spots in Taiwan’s historical friendship with the US came in 1979 when US president Jimmy Carter broke off formal diplomatic relations with Taiwan’s Republic of China (ROC) government so that the US could establish relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Taiwan’s derecognition came purely at China’s insistence, and the US took the deal. Retired American diplomat John Tkacik, who for almost decade surrounding that schism, from 1974 to 1982, worked in embassies in Taipei and Beijing and at the Taiwan Desk in Washington DC, recently argued in the Taipei Times that “President Carter’s derecognition

This year will go down in the history books. Taiwan faces enormous turmoil and uncertainty in the coming months. Which political parties are in a good position to handle big changes? All of the main parties are beset with challenges. Taking stock, this column examined the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) (“Huang Kuo-chang’s choking the life out of the TPP,” May 28, page 12), the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) (“Challenges amid choppy waters for the DPP,” June 14, page 12) and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) (“KMT struggles to seize opportunities as ‘interesting times’ loom,” June 20, page 11). Times like these can

JUNE 30 to JULY 6 After being routed by the Japanese in the bloody battle of Baguashan (八卦山), Hsu Hsiang (徐驤) and a handful of surviving Hakka fighters sped toward Tainan. There, he would meet with Liu Yung-fu (劉永福), leader of the Black Flag Army who had assumed control of the resisting Republic of Formosa after its president and vice-president fled to China. Hsu, who had been fighting non-stop for over two months from Taoyuan to Changhua, was reportedly injured and exhausted. As the story goes, Liu advised that Hsu take shelter in China to recover and regroup, but Hsu steadfastly

You can tell a lot about a generation from the contents of their cool box: nowadays the barbecue ice bucket is likely to be filled with hard seltzers, non-alcoholic beers and fluorescent BuzzBallz — a particular favorite among Gen Z. Two decades ago, it was WKD, Bacardi Breezers and the odd Smirnoff Ice bobbing in a puddle of melted ice. And while nostalgia may have brought back some alcopops, the new wave of ready-to-drink (RTD) options look and taste noticeably different. It is not just the drinks that have changed, but drinking habits too, driven in part by more health-conscious consumers and