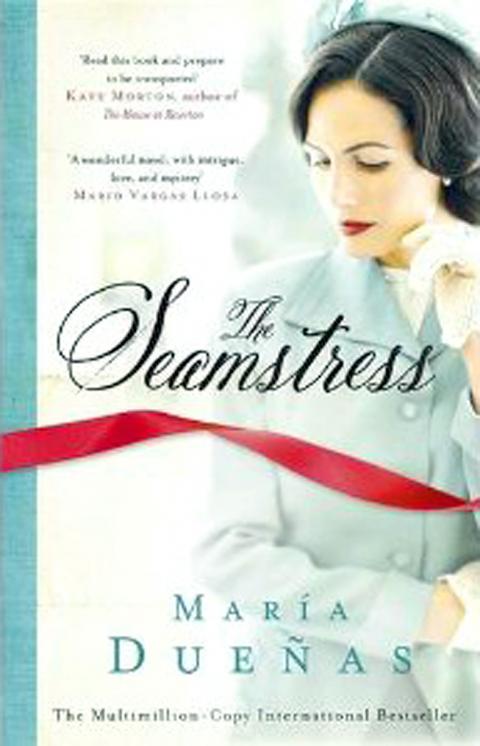

When I began this book, called in the US The Time In Between, I assumed it was a blockbuster. These kinds of books have a strange position in the modern world — they’re rarely reviewed, yet they’re what most people read. The reason is almost certainly that reviewers tend to have literary tastes, look down on best sellers, and prefer to review products they think they are going to enjoy and, more importantly, will gain status from reviewing.

But halfway through I was proved to be wrong. Up till then the story of a young woman in Madrid in the 1930s had proceeded at a modest pace, describing her love life, and following her to Spanish Morocco and the city of Tetouan. A dressmaker who loses all her money and more when her typewriter-selling lover tricks her and quickly abandons her, she manages to pay off her debts by becoming couturier to the affluent Germans and elite supporters of General Franco, first in Tetouan and then later back in Madrid.

All this seemed harmless enough, with adventures mixed with problems solved, and all in an attractively exotic period setting. Then it dawned on me that several of the major characters were actually real-life figures, and prominent players in Spanish politics in the period between the end of the Spanish Civil War and the outbreak of World War II. There’s Sir Samuel Hoare, the UK’s “Ambassador on a Special Mission,” British embassy employee and covert spy Alan Hillgarth, and, most important of all, Juan Luis Beigbeder, first seen as High Commissioner of Spanish Morocco, then later as Franco’s Foreign Minister in Madrid.

The young dressmaker establishes contact with Beigbeder after an English woman, Rosalinda Powell Fox — also an historical figure — approaches her for a spectacular evening dress at very short notice. They quickly become friends, and eventually Rosalinda offers help in getting the seamstress’ mother out of Madrid and to the safely of Tetouan. The seamstress begins to attend official functions, but things get increasingly complex when it becomes clear that Beigbeder is less than wholly in sympathy with the ideas of the Fascists in whose state he’s functioning in increasingly important roles. After she has been recruited by Hillgarth to work as a British agent, stitching messages in Morse code into the hems of dresses, the couturier is then asked by Beigbeder to arrange for some documents of a dissident nature to be taken out of the country, secure in the UK’s diplomatic bag.

This first novel took Spain by storm and has reportedly sold more than a million copies there. This is of course not automatically a recommendation — I’m a traditional book reviewer, after all — but it does to some extent explain the nature of the product. With its evocation of the North African scene — sand, sun, goats, blue-and-white awnings fluttering in a sea breeze — and its knowledge of dressmaking, of silk braid and red satin, this is a congenial, untroubling tale. It’s also well researched, able to range from references to King Alfonso XIII of Spain to the Spanish banknotes of the time, with Columbus on the 100-peseta bill and Don John of Austria on the 500-peseta bill.

Even more importantly, the author appears to get the politics right. British policy of the era was to keep Spain out of the war. Beigbeder is in sympathy, telling Franco that Spain needed wheat and oil from Britain and the US, and that in addition he should do all he could to keep the Germans out of Spain’s domestic affairs. However, the British also wanted to use Madrid’s social scene to get as much information as they could about the mind-sets and plans of individual Germans living there. Discovering such information becomes the seamstress’ first task in espionage.

There are few grand reversals in the plot, the surprise revelations of past involvements and present betrayals that are the stuff of the spy novel. Instead, it proceeds at a leisurely pace, so much so that at one point I pondered on whether the author had used Balzac’s reputed method of writing a series of sentences and then expanding each of them into a paragraph. But this isn’t really a spy story at all, rather an imaginative re-creation of a past world with romantic, political, social and quietly personal elements carefully woven together. The virtues of an upmarket dressmaker, in other words, seem to inhabit the soul of this novelist as well.

The English-language book trade needs a certain number of books of this type — novels that don’t demand a huge amount of intellectual agility on the part of the reader, but are at the same time professionally written and refuse the blockbuster’s stock in trade of gratuitous violence and graphic sex scenes. You don’t need to be a genius to enjoy The Seamstress, nor do you need to be a woman, though it will probably attract more female than male readers. Instead, it will fill up a good many empty hours. The translation by Daniel Hahn flows very smoothly, though I did have to wonder whether “inolvidable” was a leftover from the original Spanish.

Most of all, this isn’t a book stamped with any unmistakable mark of the author’s personality, at least in this English-language version. I know no more about Maria Duenas now I’ve finished the book than I did before I started it. Irony, comedy, scenes of heartbreaking tenderness or of nail-biting tension are all absent, as are purple passages. In conclusion, then, I wouldn’t go out of my way to press this novel on everyone I know, but nor would I argue strongly against it. However, Spain in the 1930s aroused intense passions all over Europe, and it’s when considering this that this novel begins to appear, for reasons that are hard to understand, surprisingly passionless.

This year will go down in the history books. Taiwan faces enormous turmoil and uncertainty in the coming months. Which political parties are in a good position to handle big changes? All of the main parties are beset with challenges. Taking stock, this column examined the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) (“Huang Kuo-chang’s choking the life out of the TPP,” May 28, page 12), the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) (“Challenges amid choppy waters for the DPP,” June 14, page 12) and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) (“KMT struggles to seize opportunities as ‘interesting times’ loom,” June 20, page 11). Times like these can

June 23 to June 29 After capturing the walled city of Hsinchu on June 22, 1895, the Japanese hoped to quickly push south and seize control of Taiwan’s entire west coast — but their advance was stalled for more than a month. Not only did local Hakka fighters continue to cause them headaches, resistance forces even attempted to retake the city three times. “We had planned to occupy Anping (Tainan) and Takao (Kaohsiung) as soon as possible, but ever since we took Hsinchu, nearby bandits proclaiming to be ‘righteous people’ (義民) have been destroying train tracks and electrical cables, and gathering in villages

Dr. Y. Tony Yang, Associate Dean of Health Policy and Population Science at George Washington University, argued last week in a piece for the Taipei Times about former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) leading a student delegation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that, “The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world” (“Ma’s Visit, DPP’s Blind Spot,” June 18, page 8). Yang contends that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has a blind spot: “By treating any

Swooping low over the banks of a Nile River tributary, an aid flight run by retired American military officers released a stream of food-stuffed sacks over a town emptied by fighting in South Sudan, a country wracked by conflict. Last week’s air drop was the latest in a controversial development — private contracting firms led by former US intelligence officers and military veterans delivering aid to some of the world’s deadliest conflict zones, in operations organized with governments that are combatants in the conflicts. The moves are roiling the global aid community, which warns of a more militarized, politicized and profit-seeking trend