The explosion ripped through Building A5 on a Friday evening last May, an eruption of fire and noise that twisted metal pipes as if they were discarded straws.

When workers in the cafeteria ran outside, they saw black smoke pouring from shattered windows. It came from the area where employees polished thousands of iPad cases a day.

Two people were killed immediately, and over a dozen others hurt. As the injured were rushed into ambulances, one in particular stood out. His features had been smeared by the blast, scrubbed by heat and violence until a mat of red and black had replaced his mouth and nose.

photo: Bloomberg

“Are you Lai Xiaodong’s father?” a caller asked when the phone rang at Lai’s childhood home. Six months earlier, the 22-year-old had moved to Chengdu, in southwest China, to become one of the millions of human cogs powering the largest, fastest and most sophisticated manufacturing system on earth.

“He’s in trouble,” the caller told Lai’s father. “Get to the hospital as soon as possible.”

In the past decade, Apple has become one of the mightiest, richest and most successful companies in the world, in part by mastering global manufacturing. Apple and its high-technology peers — as well as dozens of other American industries — have achieved a pace of innovation nearly unmatched in modern history.

However, the workers assembling iPhones, iPads and other devices often labor in harsh conditions, according to employees inside those plants, worker advocates and documents published by companies themselves. Problems are as varied as onerous work environments and serious — sometimes deadly — safety problems.

Employees work excessive overtime, in some cases seven days a week, and live in crowded dorms. Some say they stand so long that their legs swell until they can hardly walk. Underage workers have helped build Apple’s products, and the company’s suppliers have improperly disposed of hazardous waste and falsified records, according to company reports and advocacy groups that, within China, are often considered reliable, independent monitors.

More troubling, the groups say, is some suppliers’ disregard for workers’ health. Two years ago, 137 workers at an Apple supplier in eastern China were injured after they were ordered to use a poisonous chemical to clean iPhone screens. Within seven months last year, two explosions at iPad factories, including in Chengdu, killed four people and injured 77. Before those blasts, Apple had been alerted to hazardous conditions inside the Chengdu plant, according to a Chinese group that published that warning.

“If Apple was warned, and didn’t act, that’s reprehensible,” said Nicholas Ashford, a former chairman of the National Advisory Committee on Occupational Safety and Health, a group that advises the US Labor Department. “But what’s morally repugnant in one country is accepted business practices in another, and companies take advantage of that.”

Apple is not the only electronics company doing business within a troubling supply system. Bleak working conditions have been documented at factories manufacturing products for Dell, Hewlett-Packard, IBM, Lenovo, Motorola, Nokia, Sony, Toshiba and others.

Current and former Apple executives, moreover, say the company has made significant strides in improving factories in recent years. Apple has a supplier code of conduct that details standards on labor issues, safety protections and numerous other topics. The company has mounted a vigorous auditing campaign, and whenever abuses are discovered, Apple says, corrections are demanded.

But significant problems remain. More than half of the suppliers audited by Apple have violated at least one aspect of the code of conduct every year since 2007, according to Apple’s reports.

“Apple never cared about anything other than increasing product quality and decreasing production cost,” said Li Mingqi, who until April worked in management at Foxconn Technology [Group] (富士康科技集團), one of Apple’s most important manufacturing partners. Li, who is suing Foxconn over his dismissal, helped manage the Chengdu factory where the explosion occurred.

Apple was provided with extensive summaries of this article, but the company declined to comment. The reporting is based on interviews with more than three dozen current or former employees and contractors, including a half-dozen current or former executives with firsthand knowledge of Apple’s supplier responsibility group, as well as others within the technology industry.

THE ROAD TO CHENGDU

Foxconn’s factory in Chengdu, Lai Xiaodong knew, was special. Inside, workers were building Apple’s latest, potentially greatest product: the iPad.

When Lai landed a job repairing machines at the plant, one of the first things he noticed were the almost blinding lights. Shifts ran 24 hours a day, and the factory was always bright. At any moment, there were thousands of workers standing on assembly lines or sitting in backless chairs, crouching next to large machinery, or jogging between loading bays. Some workers’ legs swelled so much they waddled. “It’s hard to stand all day,” said Zhao Sheng, a plant worker.

Banners on the walls warned the 120,000 employees: “Work hard on the job today or work hard to find a job tomorrow.” Apple’s supplier code of conduct dictates that, except in unusual circumstances, employees are not supposed to work more than 60 hours a week. But at Foxconn, some worked more, according to interviews, workers’ pay stubs and surveys by outside groups. Lai was soon spending 12 hours a day, six days a week inside the factory, according to his paychecks. Employees who arrived late were sometimes required to write confession letters and copy quotations. There were “continuous shifts,” when workers were told to work two stretches in a row, according to interviews.

Lai’s college degree enabled him to earn a salary of around US$22 a day, including overtime — more than many others. When his days ended, he would retreat to a small bedroom just big enough for a mattress, wardrobe and a desk.

Those accommodations were better than many of the company’s dorms, where 70,000 Foxconn workers lived, at times stuffed 20 people to a three-room apartment, employees said. Last year, a dispute over paychecks set off a riot in one of the dormitories.

Foxconn, in a statement, disputed workers’ accounts of continuous shifts, extended overtime, crowded living accommodations and the causes of the riot. The company said that its operations adhered to customers’ codes of conduct, industry standards and national laws. “Conditions at Foxconn are anything but harsh,” the company wrote. Foxconn also said that it had never been cited by a customer or government for underage or overworked employees or toxic exposures.

“All assembly line employees are given regular breaks, including one-hour lunch breaks,” the company wrote, and only 5 percent of assembly line workers are required to stand to carry out their tasks. Work stations have been designed to ergonomic standards, and employees have opportunities for job rotation and promotion, the statement said.

APPLE’S CODE OF CONDUCT

In 2005, some of Apple’s top executives gathered inside their Cupertino, California, headquarters for a special meeting. Other companies had created codes of conduct to police their suppliers. It was time, Apple decided, to follow suit. The code Apple published that year demands “that working conditions in Apple’s supply chain are safe, that workers are treated with respect and dignity, and that manufacturing processes are environmentally responsible.”

But the next year, a British newspaper, the Mail on Sunday, secretly visited a Foxconn factory in Shenzhen, China, where iPods were manufactured, and reported on workers’ long hours, push-ups meted out as punishment and crowded dorms. Executives in Cupertino were shocked.

Apple audited that factory, the company’s first such inspection, and ordered improvements. Executives also undertook a series of initiatives that included an annual audit report, first published in 2007. By last year, Apple had inspected 396 facilities — including the company’s direct suppliers, as well as many of those suppliers’ suppliers — one of the largest such programs within the electronics industry.

Those audits have found consistent violations of Apple’s code of conduct, according to summaries published by the company. In 2007, for instance, Apple conducted over three dozen audits, two-thirds of which indicated that employees regularly worked more than 60 hours a week. In addition, there were six “core violations,” the most serious kind, including hiring 15-year-olds as well as falsifying records.

Over the next three years, Apple conducted 312 audits, and every year, about half or more showed evidence of large numbers of employees laboring more than six days a week as well as working extended overtime. Apple found 70 core violations over that period.

Last year, the company conducted 229 audits. There were slight improvements in some categories and the detected rate of core violations declined. However, within 93 facilities, at least half of workers exceeded the 60-hours-a-week work limit. A similar number showed employees working more than six days a week.

“If you see the same pattern of problems, year after year, that means the company’s ignoring the issue rather than solving it,” said one former Apple executive with firsthand knowledge of the supplier responsibility group. “Noncompliance is tolerated, as long as the suppliers promise to try harder next time. If we meant business, core violations would disappear.”

Apple says that when an audit reveals a violation, the company requires suppliers to address the problem within 90 days and make changes to prevent a recurrence. “If a supplier is unwilling to change, we terminate our relationship,” the company says on its Web site.

The seriousness of that threat, however, is unclear. Apple has found violations in hundreds of audits, but fewer than 15 suppliers have been terminated for transgressions since 2007, according to former Apple executives.

THE EXPLOSION

On the afternoon of the blast at the iPad plant, Lai Xiaodong telephoned his girlfriend, as he did every day. They had hoped to see each other that evening, but Lai’s manager said he had to work overtime, he told her.

He had been promoted quickly at Foxconn, and after just a few months was in charge of a team that maintained the machines that polished iPad cases.

The morning of the explosion, Lai rode his bicycle to work. The iPad had gone on sale just weeks earlier, and workers were told thousands of cases needed to be polished each day. The factory was frantic, employees said. Rows of machines buffed cases as masked employees pushed buttons. Large air ducts hovered over each station, but they could not keep up with the three lines of machines polishing nonstop. Aluminum dust was everywhere.

Dust is a known safety hazard. In 2003, an aluminum dust explosion in Indiana destroyed a wheel factory and killed a worker. In 2008, agricultural dust inside a sugar factory in Georgia caused an explosion that killed 14.

Two hours into Lai’s second shift, the building started to shake, as if an earthquake was under way. There was a series of blasts, plant workers said. The toll would eventually count four dead, 18 injured.

At the hospital, Lai’s girlfriend saw that his skin was almost completely burned away.

Eventually, his family arrived. Over 90 percent of his body had been seared.

After Lai died, a team of Foxconn workers drove to Lai’s hometown and delivered a box of ashes. The company later wired a check for about US$150,000.

Foxconn, in a statement, said that at the time of the explosion the Chengdu plant was in compliance with all relevant laws and regulations, and “after ensuring that the families of the deceased employees were given the support they required, we ensured that all of the injured employees were given the highest quality medical care.” After the explosion, the company added, Foxconn immediately halted work in all polishing workshops, and later improved ventilation and dust disposal, and adopted technologies to enhance worker safety.

In its most recent supplier responsibility report, Apple wrote that after the explosion, the company contacted “the foremost experts in process safety” and assembled a team to investigate and make recommendations to prevent future accidents.

Last month, however, seven months after the blast that killed Lai, another iPad factory exploded, this one in Shanghai. Once again, aluminum dust was the cause, according to interviews and Apple’s most recent supplier responsibility report. That blast injured 59 workers, with 23 hospitalized.

In its most recent supplier responsibility report, Apple wrote that while the two explosions both involved combustible aluminum dust, the causes of the blasts were different. The company declined, however, to provide details. The report added that Apple had now audited all suppliers polishing aluminum products and had put stronger precautions in place.

For Lai’s family, questions remain.

“We’re really not sure why he died,” said Lai’s mother, standing beside a shrine she built near their home. “We don’t understand what happened.”

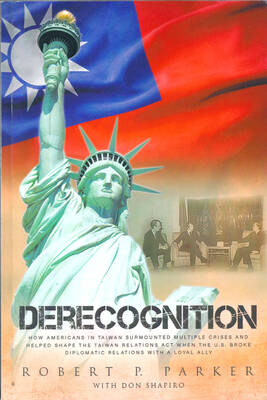

One of the biggest sore spots in Taiwan’s historical friendship with the US came in 1979 when US president Jimmy Carter broke off formal diplomatic relations with Taiwan’s Republic of China (ROC) government so that the US could establish relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Taiwan’s derecognition came purely at China’s insistence, and the US took the deal. Retired American diplomat John Tkacik, who for almost decade surrounding that schism, from 1974 to 1982, worked in embassies in Taipei and Beijing and at the Taiwan Desk in Washington DC, recently argued in the Taipei Times that “President Carter’s derecognition

This year will go down in the history books. Taiwan faces enormous turmoil and uncertainty in the coming months. Which political parties are in a good position to handle big changes? All of the main parties are beset with challenges. Taking stock, this column examined the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) (“Huang Kuo-chang’s choking the life out of the TPP,” May 28, page 12), the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) (“Challenges amid choppy waters for the DPP,” June 14, page 12) and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) (“KMT struggles to seize opportunities as ‘interesting times’ loom,” June 20, page 11). Times like these can

June 23 to June 29 After capturing the walled city of Hsinchu on June 22, 1895, the Japanese hoped to quickly push south and seize control of Taiwan’s entire west coast — but their advance was stalled for more than a month. Not only did local Hakka fighters continue to cause them headaches, resistance forces even attempted to retake the city three times. “We had planned to occupy Anping (Tainan) and Takao (Kaohsiung) as soon as possible, but ever since we took Hsinchu, nearby bandits proclaiming to be ‘righteous people’ (義民) have been destroying train tracks and electrical cables, and gathering in villages

Dr. Y. Tony Yang, Associate Dean of Health Policy and Population Science at George Washington University, argued last week in a piece for the Taipei Times about former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) leading a student delegation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that, “The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world” (“Ma’s Visit, DPP’s Blind Spot,” June 18, page 8). Yang contends that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has a blind spot: “By treating any